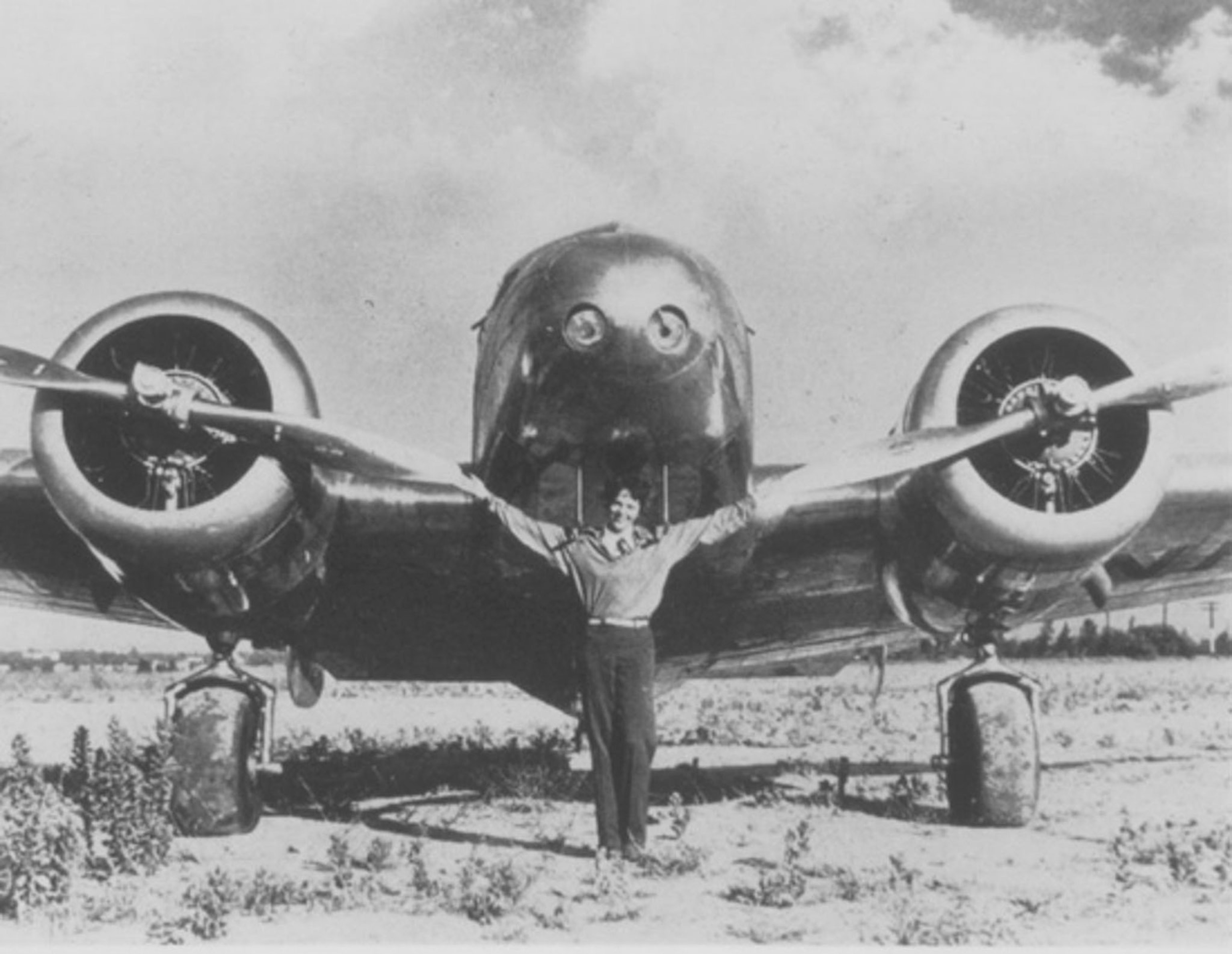

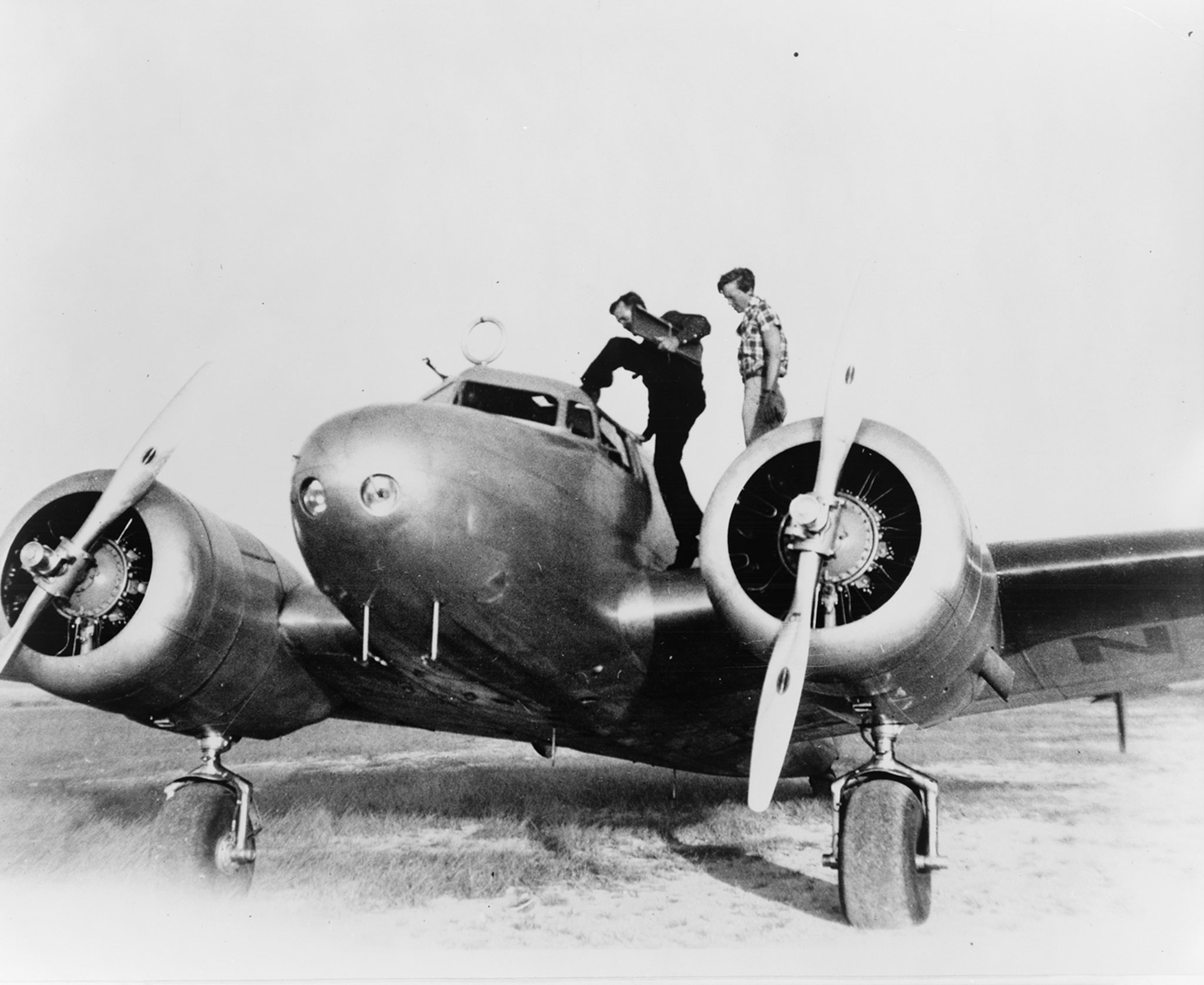

Nikumaroro Island, Kiribati — Summer Farrell looked out on the island of Nikumaroro from the back deck of the E/V Nautilus. A pilot and remote control vehicle (ROV) operator, Farrell was wondering where Amelia Earhart could have landed her Lockheed Electra 10e.

Nautilus arrived at the island on the previous day as part of a National Geographic-sponsored expedition. Farrell, a member of the Nautilus crew, had been given a crash course on the theory the expedition was exploring—whether Earhart landed her plane on Nikumaroro in 1937 when she couldn’t find the next stop on her world flight.

Now Farrell was considering the evidence. The sun was setting on the uninhabited coral atoll, a strip of dense green vegetation banded by a narrow beach with a reef stretching before it. Where the beach fell away and the reef widened, it was possible to catch a glimpse of the turquoise lagoon at the center of the island.

Farrell assessed the reef and the lagoon. The reef, though relatively level, was pockmarked and hard as stone while the cloudy lagoon’s depth would be indiscernible from the air. Earhart “had retractable landing gear so a water landing would have been safer” with a smooth fuselage, said Farrell, “but if the idea was to land and take off again, maybe the reef would be better, especially if she had to crash land.”

The wreck of the S.S. Norwich City, a freighter which ran aground in 1929, divides the reef between the northern tip of the island and the opening to the lagoon. “You only need 1,500 to 2,000 feet” to land, said Farrell, gesturing at the reef. “That’s a significant stretch.”

Speculation about Amelia Earhart’s disappearance is nearly irresistible, especially for those involved in an expedition to find out what happened to her. Members of the crew have been asking themselves—while performing such eye-straining work as scanning ROV footage for plane parts or sifting through white knobby coral in search of white knobby bones—what Earhart did some 82 years ago and why she did it.

Over on the southeastern end of Nikumaroro Island, John Clauss and Andrew McKenna considered the question of Earhart’s landing site as they perched ankle-deep in coral rubble at the base of the ren tree where forensic dogs signaled two years ago that someone had died. They are both pilots themselves (McKenna owns a flight school) and longtime members of the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), which has promoted the hypothesis that Earhart landed on Nikumaroro and died there as a castaway.

TIGHAR has collected evidence over the years that suggests Earhart landed on the reef north of the Norwich City wreckage. A British officer scouting the island for colonial settlement a few months after the aviator disappeared snapped a picture that shows a blurry image that some analysts have said is landing gear. And people who lived in the Nikumaroro settlement as children later reported finding plane parts.

But Clauss and McKenna have other reasons for believing Earhart did not land in the lagoon. McKenna points out that at that stage in aviation history pilots regularly landed in irregular places. “There weren’t airports everywhere,” he says. “That’s why she had huge tires.” And a plane of similar size had successfully landed on a reef just nine months previously. “She would have known about that.”

“I don’t think it’s fair to second guess what she did,” adds Clauss. “Very few people remember what aviation was like before World War II. Everything we deal with now—rules, conventions—all came out of World War II. Flying [before then] was the wild, wild west.” In that context, landing on a rocky reef at low tide would be a reasonable thing to do.

While sitting in the shade of a coconut palm on the lee side of the island, Tom King, the senior member of the land crew and an archaeologist formerly with TIGHAR, cites a reason that has nothing to do with aviation for a likely reef landing. “Earhart did not intend for this to be the end,” said King. “She intended to take off and finish her world flight.” But if the TIGHAR theory is true, landing on the rough coral damaged the plane, possibly crippling the landing gear, and she couldn’t take off again.

Back on the Nautilus, Robert Ballard, the man who found the Titanic, is searching the waters off Nikumaroro for the Electra’s remains. But that doesn’t stop him from speculating in his off hours about where else she might have landed. Could she have touched down on the windward side of the island or possibly on another island altogether? Based on how much gas she had left, he wondered, “What other islands were reachable and uninhabited and haven’t been searched?” He crunched the numbers and the answer is very few.

The search for Amelia Earhart is an endless puzzle, and a challenge that Ballard relishes. So do the other members of the expedition, who have puzzled over how long Earhart could have survived on the island, what she ate, whether the coconut crabs consumed her, if her plane could have floated intact over the reef, whether rescuers tried hard enough to find her and, most poignantly, how the ardent feminist and pacifist might have changed the world if she had lived. We may never know the answers to some of these questions but the speculation will continue as long as the mystery remains unsolved.