Excerpt: Jerusalem in the time of Jesus

A European priest looks 1,500 years into the past and imagines the Holy City at the birth of Christianity.

Christiaan van Adrichom almost certainly never visited Jerusalem before making this map in 1584. He was a Catholic priest working in Cologne, in what is now Germany, at a time when the Holy Land had been in Muslim hands for centuries, making it a difficult and potentially dangerous place for Christian pilgrims to visit. Nevertheless, Adrichom managed to create an enormously popular map that not only allowed European Christians to imagine a trip most of them would never be able to take, but also took them back in time to picture the city as it existed during the time of Christ.

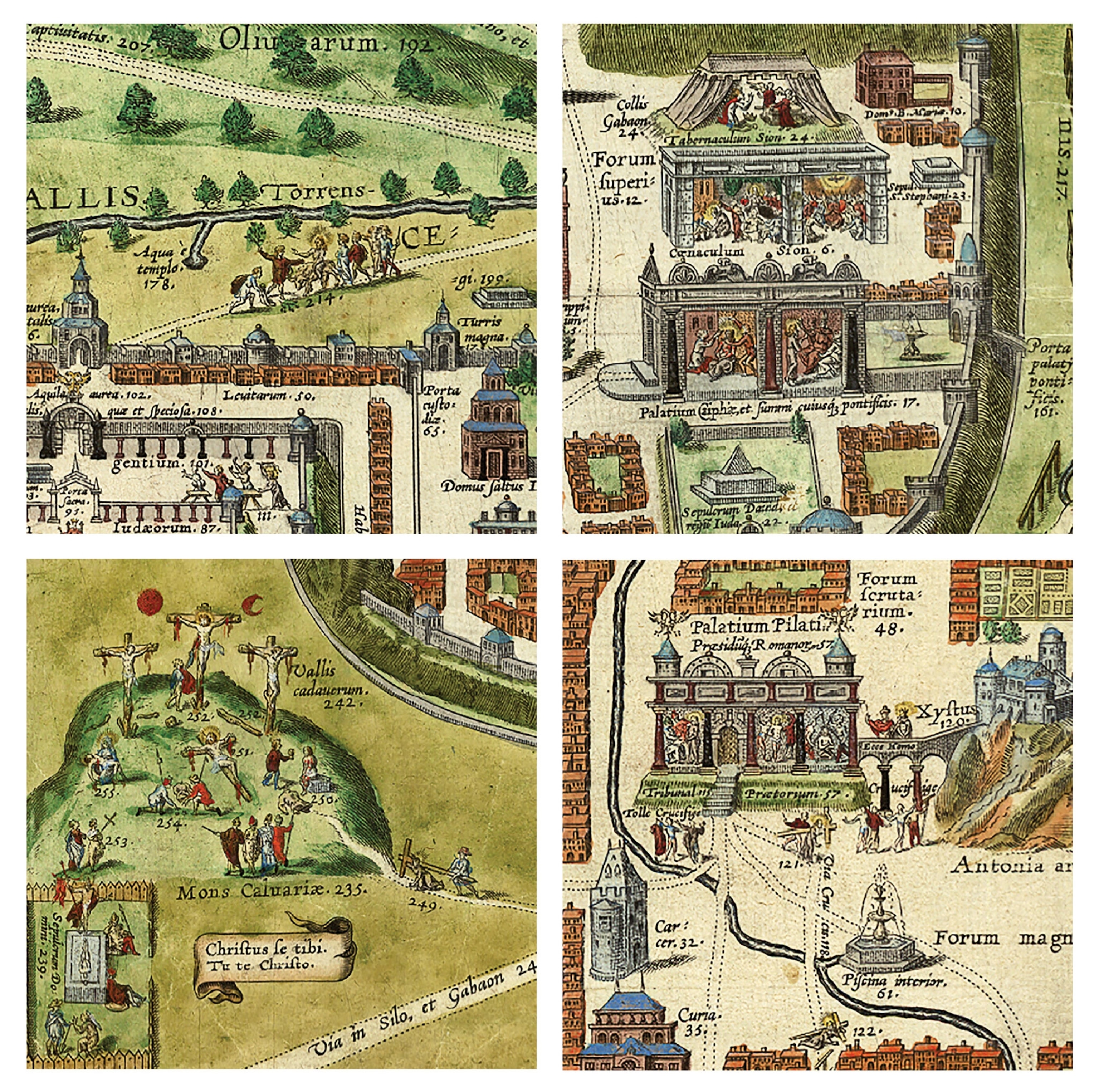

The map is packed with at least 270 landmarks and references to Christian tradition, all numbered and keyed to captions in a booklet that accompanied it. Adrichom drew from the work of previous mapmakers, as well as from the Bible and accounts by earlier scholars and pilgrims.

The map looks down on Jerusalem from the west, with east at the top of the map. The orderly grid of streets appears to be based on an overly simplified description of the city by first-century historian Flavius Josephus. In contrast to the thick limestone buildings that would have dominated Jerusalem in the time of Christ, the buildings on Adrichom’s map are suspiciously similar in style to the more ornate architecture of 16th-century Europe.

Show and tell

Key episodes from the life of Jesus are strewn across the map. He arrives at Jerusalem on a donkey, as described in the New Testament, surrounded by disciples and preceded by a figure spreading branches in the road ahead of them (number 214). The Last Supper, where Jesus predicted his betrayal by Judas, appears just inside the city walls (number 6), and Jesus’ trial before Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who ordered his execution, plays out just left of center (number 115).

From there, Adrichom portrays Jesus carrying a wooden cross to Mount Calvary (number 235), where he was crucified, as depicted by images of 14 distinct events. That number is one that seems to have stuck. Even today, some Christians observe Good Friday by reenacting Jesus’ path, pausing to pray at 14 Stations of the Cross.

Adrichom illustrates events from the final days of Jesus’ life as if they are happening simultaneously, but he performs even greater feats of time warping. The invaders who conquered Jerusalem through its history encircle the city together, all at once. The Assyrians who invaded in the eighth century B.C. have set up their tents on the right side of the map, while the Chaldeans who laid siege to the city in the sixth century B.C. are camped out on the left, not far from the Roman conquerors who arrived in A.D. 70.

Armchair travelers

Jerusalem was a minor city in the Ottoman Empire in Adrichom’s time, but its religious significance meant it still loomed large in the European imagination. Since the invention of the printing press a century earlier, histories, travel guides, and other books about the Holy Land had become increasingly popular and available for people to buy.

But what Europeans were looking for in these works wasn’t something they could actually use to plan a trip, writes historical geographer Rehav Rubin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in a 1993 article in the biblical archaeology magazine Bible Review. “Few Europeans actually traveled to Jerusalem. They bought maps and books reflecting their interest in the ideas and events associated with the Holy City—not its physical details.”

Adrichom’s map did exactly that. It was printed in several editions over the following centuries and translated into several languages, a testament to its popularity. For nearly 300 years, the vision of Jerusalem held by European Christians was shaped to a large degree by this colorful and highly imaginative map.