How millions of high-risk Americans are coping with the pandemic

Amid her own health crisis, a photographer sought to portray those most vulnerable to COVID-19—and understand how they’ve managed.

In 2009, Amy Bacon, a seemingly healthy resident of Grand Blanc, Michigan, suffered sudden cardiac arrest. By the time medics got to her, she’d been without oxygen for four minutes. The odds of survival were around six percent. Three years later, she was diagnosed with congestive heart failure and received a heart transplant. Then, on April 16, 2020, Bacon tested positive for COVID-19.

At the time, there was little data on how someone with her conditions would fare. So she consulted with her transplant team, who told her not to go to the hospital and risk picking up an infection. After her heart failure and transplant, the 51-year-old had a startling thought: “COVID was going to be the one to take me out?”

The virus didn’t take her life, but it has affected nearly every aspect of it. She is among an estimated 40 percent of Americans with severe medical issues that could be compounded by COVID-19, or who are immunosuppressed and can’t fight it. She also is among 10 individuals photographer Sarah Rice profiled in an effort to document the effects of the pandemic on those most at risk.

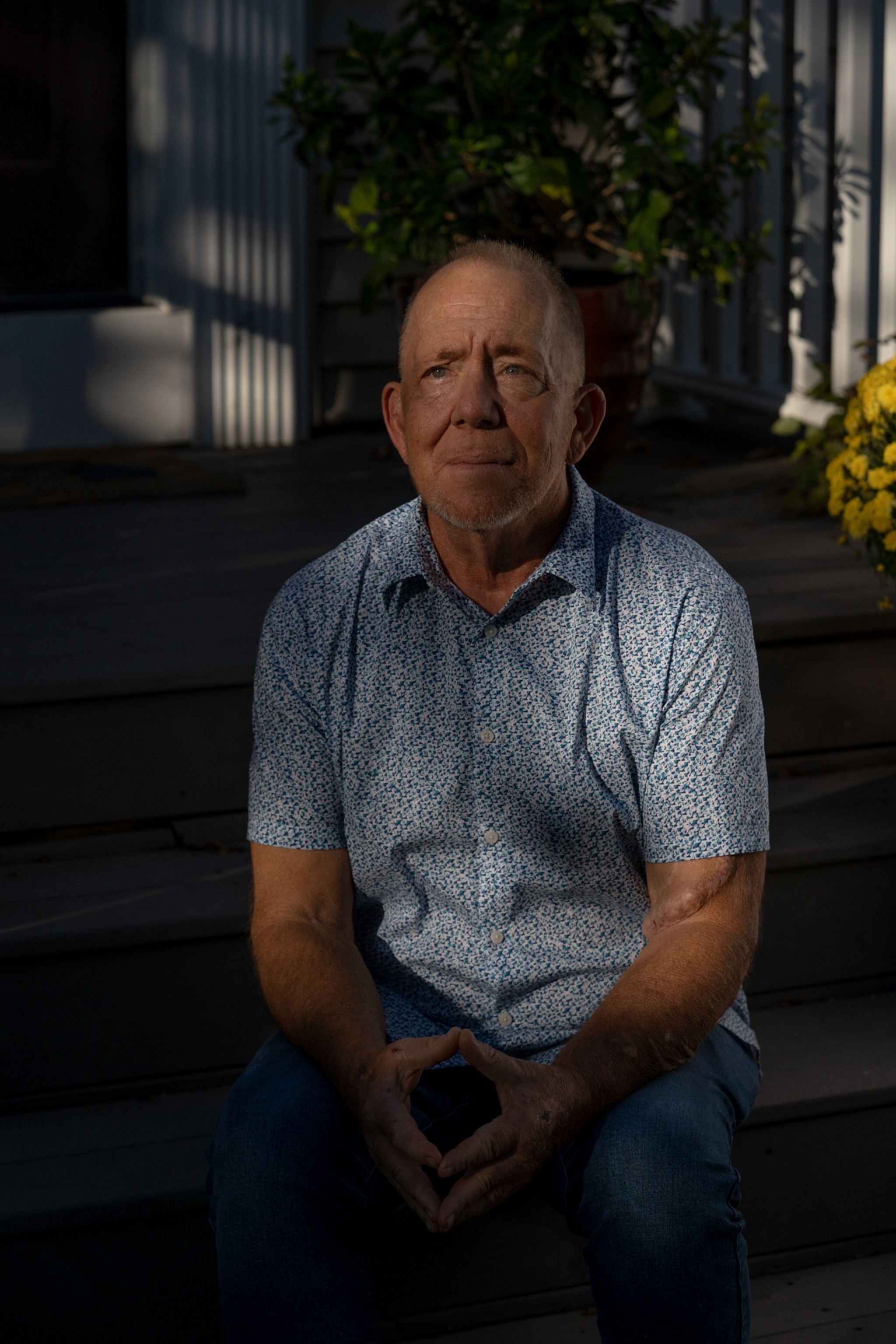

For sisters Olivia and Reece Ohmer, 18 and 20, who have type 1 diabetes along with other autoimmune diseases, the pandemic meant missing milestones like the prom. For Sheila Jackson, a graphic designer, COVID-19 unleashed a frightening backdrop to her kidney transplant. For Howard French, a 76-year-old whose brain continuously hemorrhages, it was the cause of isolation from his kids and grandkids.

“The pandemic amplifies every vulnerability,” Rice says.

Some high-risk individuals have continued working and going to school as safely as they can. Others have hunkered down, relying on their support systems for basic tasks. Some are able to get the vaccine, others have immune systems that don’t create antibodies. All have upended their lives to adapt to the threat of COVID-19.

Conflicting approaches

“This is a once in a century event,” says Lisa Maragakis, the hospital epidemiologist for the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and a pandemic preparedness expert. Such a crisis always deals its brunt to the most vulnerable. During the influenza epidemic of 1918, the virus spread quickly through cramped neighborhoods of immigrants and institutes for the disabled and for older adults. A hundred years later, COVID-19 played out similarly.

Rather than fluctuating between lockdown and opening up, Maragakis believes a more moderate approach would have been more effective at containing the viral spread and could be sustained long-term. Maragakis uses her hospital as an example: layers of protection—masks, ventilation, cleaning—has allowed high-risk staff to do their jobs safely in the epicenter of a deadly virus.

This type of cooperation would open the world back up to those at high risk, she says. But the whole system has to be aligned. Outside of a hospital setting, increasingly, it’s left to individuals to choose which precautions to take. “This has shown us, in such a dramatic way, that little actions can mean life or death to very vulnerable people,” says Maragakis.

The fears that pervaded this segment of the population were not just of the virus itself—but of the medical care they could expect. Early in the pandemic, there were signs that those who fell into a high-risk category could receive a poorer quality of care than their healthy counterparts.

According to a study by the Center for Public Integrity, 25 states had health policies that allowed hospitals to deprioritize people with disabilities or chronic conditions that could lower their odds of surviving COVID-19. Some specifically instructed moving patients with certain diagnoses, including dementia and cystic fibrosis, a genetic lung disease, to the back of the line for treatment if rationing of equipment like ventilators was needed.

Michael Remblis wasn’t surprised. Rembis studies the history of institutionalization and runs the Center for Disability Studies at the University of Buffalo. To him, and others, it showed a lingering legacy of Eugenics in the United States, when people with disabilities were actively removed from society, and it stung of ableism, a power structure that ignores those with less physical ability.

“From my perspective it just exacerbated and compounded the social exclusion of people who were already removed from society,” says Remblis. “What limited access they had to the world outside their own homes was eliminated. The poverty rates among people with chronic conditions and severe disabilities is really high. They don't have access to Zoom or the internet, and they’re not in the type of jobs, if they have one, where they can work from home.”

Extreme isolation breeds depression, suicidal thoughts, and even additional health conditions such as malnutrition. Many people have put off preventative check-ups or important surgeries over the past two years due to fears of contracting the virus.

“The pandemic highlighted a lot of inequalities in society, [like] unequal access to healthcare, housing, and food,” says Remblis. “And disabled people were essentially saying that’s the way their lives are all the time, even in the best of times.”

Highlighting inequalities

This access hurdle was a thread linking the people Rice photographed. To survive, the support system they’d had before needed to be pandemic-proof. Nearly everyone leaned heavily on their families and networks to compete basic tasks that were now unsafe for them to do. Connie Jones, a 63-year-old who lives in an apartment complex in Grand Rapids, had suffered three strokes and lives with a heart defect. For many months, she relied on volunteers with the American Heart Association to bring her groceries, and for a year she interacted with no one else.

Meeting this group of high-risk Americans, who cut across social, racial, and age demographics, was an eye-opener for Rice. When Rice spoke with Bacon, the transplant survivor, she heard the ups and downs of chronic illness. At times, Bacon was loving life; in other moments, she complained of being at wit’s end due to her years of migraines, the pile of medications, and the other health issues that developed after she got COVID-19.

Rice understood. In 2010, she was diagnosed with a brain tumor and underwent surgery. It returned and she began radiation. A severe motorcycle accident left her with more injuries. “I can relate to being so exhausted by all these things,” she says, “but also so stoked to be here and very much in love with the life I have.”

Rice moved from Maine back to her home state of Michigan, in part to begin this project. She aimed to photograph a diverse mix of people and also the effects of confinement during cold winter months. She wanted to understand the support systems these people had, and whether pandemic fatigue had frayed that safety net.

Rice was gearing up to begin in November 2020 when her health took a turn. She was hit by vertigo and extreme light sensitivity. She was confined to bed, unable to look at the glow from a screen or stand up. She stayed horizontal, in her father’s basement, for months.

When her father and stepmother tested positive for COVID-19, Rice had to move to an Airbnb. Suddenly she was relying on the network of support she meant to probe with her photographs. She lay in bed entertained by funny audio messages sent by her friends. One called her every day to check in and read a story over the phone. Another delivered Christmas dinner to her door.

By February, Rice could stand up and open her eyes with sunglasses on. By May, she could look at her computer for an hour at a time. In August, she drove to interviews with her head and neck secured by a brace her physical therapist had built into the car.

Embarking on this project was the first time she had been in touch with others who suffered from such life altering conditions. “I’ve spent a lot of my life trying to live with this not defining my life,” says Rice of her own health issues. “Which is why I didn’t tell anyone for years. But if you don't tell anyone you don't get perspective.”

After she photographed her subjects Rice stood in her yard, framing herself in the same style as her subjects, and took a self-portrait.