In one of Egypt’s most spiritual places, Bedouins find peace and resilience

Connecting with Bedouin roots in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt: "What I always see is an unconditional love for the land."

Sinai Peninsula, Egypt — Driving on the narrow road toward the imposing mountains of the Sinai Peninsula, the wind is cold, but the sun is warm and clean air rushes into my lungs. I take out my driver’s license in preparation for the upcoming military checkpoint. “Where are you heading?” comes the usual question. “St. Katherine,” I respond, referring to the St. Katherine Protectorate, an Egyptian national park that is home to the Bedouins. The officer looks skeptical. I can almost hear his thoughts, which I presume to be along the lines of this: Bedouin women don’t drive, and they don’t wear pants.

I first came to this sparsely populated desert region, situated between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, 15 years ago. I was a teenager running away from Cairo, longing for something I couldn’t comprehend. I didn’t know then about my Bedouin ancestry, nor that I would find a home away from home in these mountains. What little I knew about Sinai had come from my father’s stories about when he was stationed here during the war and Israeli occupation in the early 1970s.

My attachment to Sinai has grown beyond stories since that time. On my first visit to the St. Katherine Protectorate, I was taken in by a Bedouin family. Sheikh Ibrahim treated me as one of his children, and his daughters, Zeinab and Mariam, became like sisters to me. Then, in 2018, I was part of an effort—in collaboration with the Bedouin villages of Al Tarfa and Sheikh Awad—to open a volunteer-based clinic, which provides free medical services to a community that has long struggled to find proper medical care. Bedouins came from different tribes and regions in Sinai. Everyone is welcome.

The Jebeliya tribe, the oldest indigenous community, has been inhabiting the region for more that 1,400 years. Tribal members protect the sacred land, home to the ancient St. Katherine Monastery, and Mount Sinai (known in Arabic as Jabal Moussa, or the “mountain of Moses"), where Moses received the Ten Commandments, according to Jewish, Muslim and Christian teachings. The community has survived wars, forced relocation deeper into the mountains, drought and pandemics.

Bedouins remain keepers of the land, despite a long list of challenges: limited medical care, declining economic prospects, COVID-19, and a lack of infrastructure and access to education.

Over the years, they also have been victims of discrimination, stigma and stereotyping. During the Israeli occupation between 1967 and 1982, Bedouins insisted on remaining on their land and were labeled by the larger Egyptian public as traitors for doing so. Their resistance to the occupation—by working as guides to help Egyptian Army forces get through the mountains without detection—was overlooked. Too often, they are misrepresented as closed off and hostile to modern ways.

Naturally isolated from the rest of Egypt with their settlements nestled between the high mountains, among them Mount Sinai and Oum Shomar, the Bedouins find peace in solitude. Today, the land that serves as their home is considered one of the most spiritual places in Egypt.

With the job losses that came after COVID, many in the community are no longer able to afford to pay for medicine. The clinic was forced to close due to the pandemic.

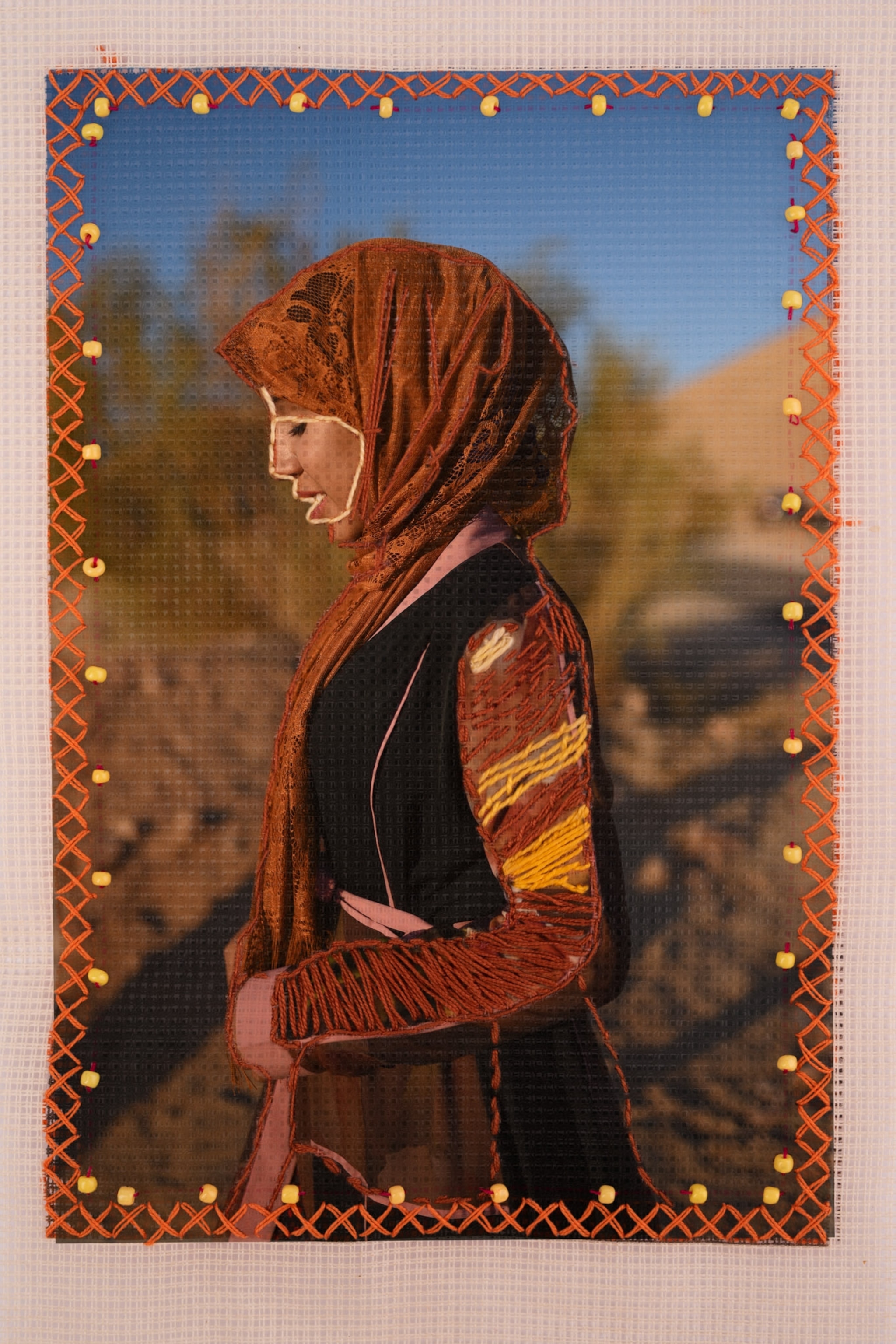

Forms of self-expression

Before COVID-19, the community had been involved in a four-year project that used embroidery and poetry with some of my images to engage in forms self-expression. Until the 1990’s, women were prohibited from being seen by men from other tribes without consent. As part of this community effort, female Bedouins added embroidery to self-portraits printed on fabric. This way, they controlled what to reveal or conceal.

-cropped.jpg)

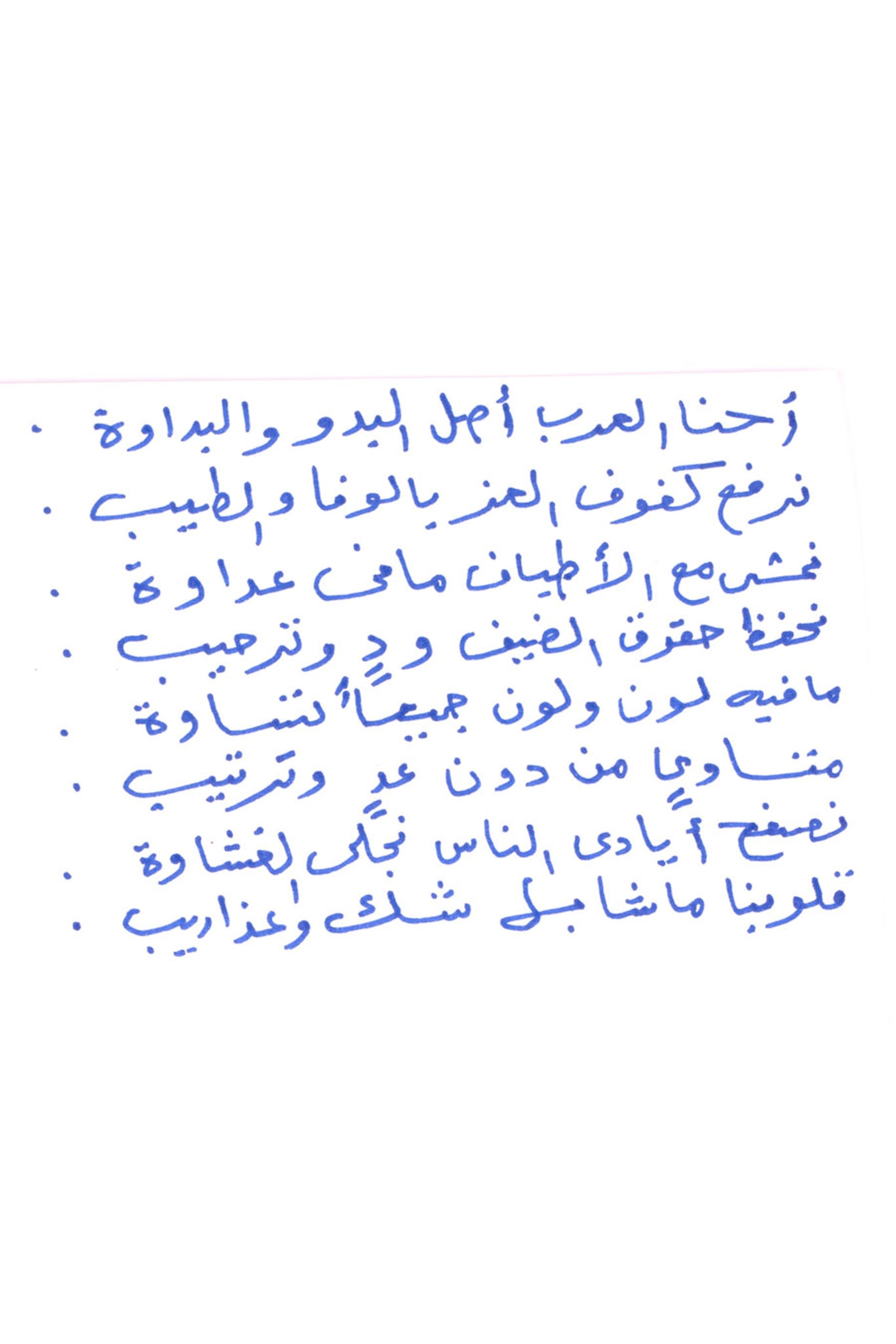

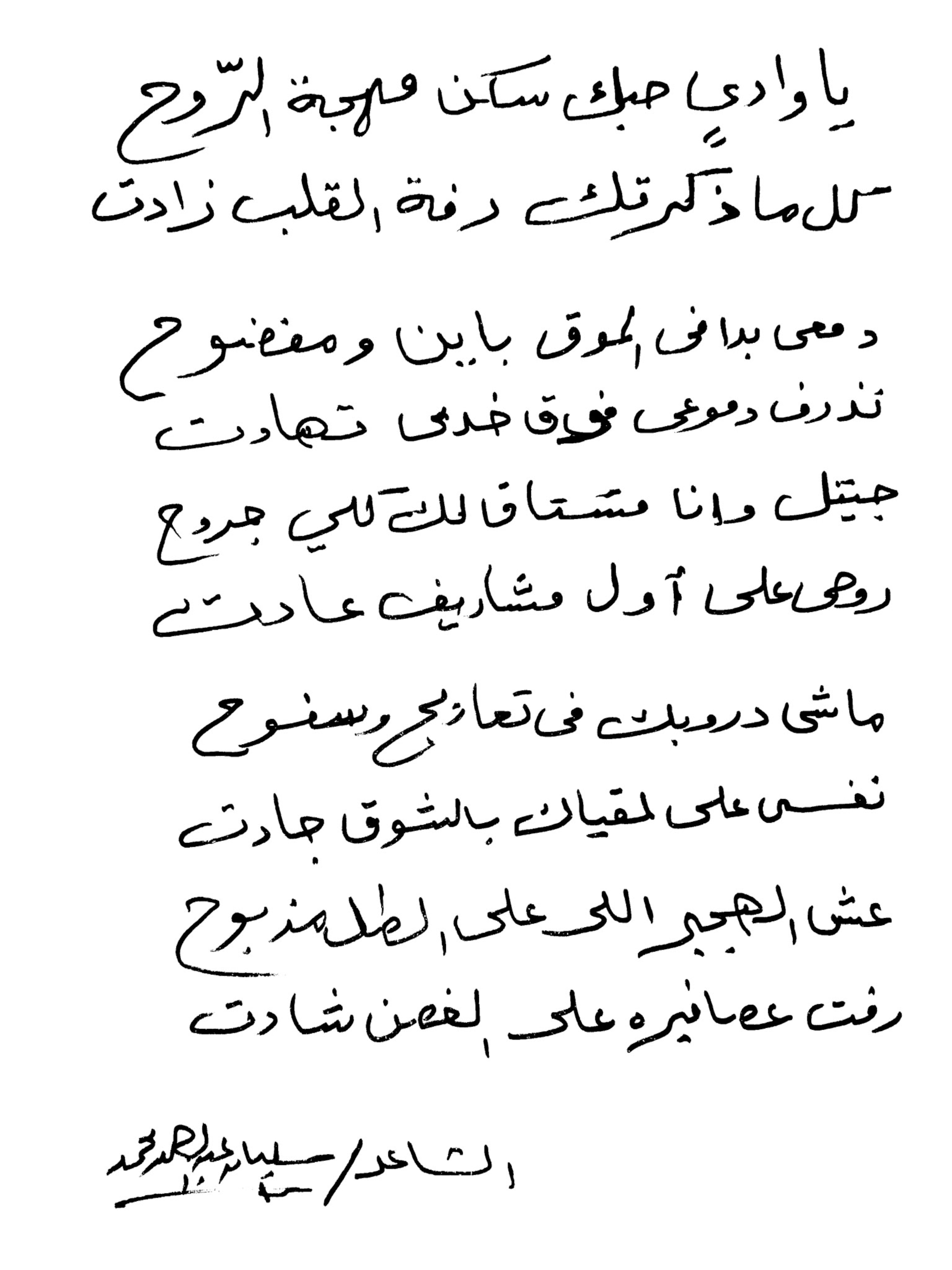

Poetry also plays a big role in the Bedouin culture. Males in particular hold poetry circles during holidays, weddings and on Friday evenings. In this participatory project, some members of the community wrote poems that captured their feelings toward my images. This collaboration resulted in a series of diptychs. The poems seen below were both written by Seliman Abdel Rahman Abu Anas.

We are the Arabs the genuine Bedou'

We carry loyalty and kindness at heart

We walk with all kinds with no hate

We protect our guests and welcome them

No color but all color equally Equals without calculations.

We shake hands to form bonds Our hearts has no doubt but agony

Oh valley, your love is a home for the soul’s joy

Whenever I see you my heart grows

I come to you in longing full of pains

My soul returns to me as I approach your grounds

Love for the land

I return to Sinai every few months, hauling medicine for those suffering from chronic illnesses like diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and cancer. I’ve been back five times since the pandemic began to spread just over a year ago to deliver medical aid. With each visit, I am hopeful that the following month we will be able to reopen the clinic.

My next visit later this month will be different—I’ll be attending Zeinab’s wedding. I’m looking forward to witnessing old traditions that remain intact: camel races in celebration of the bride and groom and village feasts. Some traditions have already disappeared: the fully embroidered Bedouin dress with pure gold accessories and the houses built with sturdy rocks collected from the mountains, camouflaging the entire village in its surroundings.

Other traditions such as handmade crafts have evolved, prompted by a younger generation of Bedouins who want to keep pace with the world. What I always see is an unconditional love for the land. This interconnectedness runs through my blood and is what pulled me here 15 years ago to find my roots and my way home.

Rehab Eldalil is a visual storyteller based in Egypt. Her work focuses on the broad theme of identity explored through participatory creative practices.

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Eldalil's work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers working to inspire, educate, and better understand human history and cultures.