Look out! A veteran fire spotter shares the view from her mountaintop perch

Even in bad fire years, there’s a rhythm to the days, writes Karen Reeves from her tower in Montana's Glacier National Park.

Glacier National Park, Montana — A flash of light—BAM! An explosion—and this old, wooden tower jiggles. I sit bolt upright out of a sound sleep. I’m not thinking clearly, but I know I’m on a mountaintop, in a fire tower, in the middle of the night, and out the window I see flames. A lightning storm is in progress, and there’s fire down by the outhouse. It seems.

My daughter is visiting and is in her sleeping bag on the floor. I tell her I’m going to put the fire out and am out the door. I go downstairs to the first floor where there are tools and supplies. With my headlamp on high, I pull the Forest Service version of a backpack super soaker off the wall, fill it from a five-gallon container of water, sling it across my back, and step out into the night storm.

Oh!

All that activity, and now getting lashed by wind and rain, I’m fully awake. What I perceived as a small fire nearby is actually a rather large one 2,000 feet below me. I walk back upstairs.

“Where did you go?” my daughter asks.

At first light I call in the fire to the dispatch team. By 10:30, 10 smoke jumpers parachute in and spend the next week putting out the fire.

That was 2018, in mid-August.

Summer 2021, and once again my vantage point is from the same nearly 90-year-old two-story tower that sits at 7,000 feet atop a forested ridge in northwestern Montana’s Glacier National Park.

This summer is hot! hot! hot! beginning with 90-to-100-degree temps in June. Now July is continuing with more 90-plus-degree days and no rain. Most of the West is panting, and, locally, smoke from Oregon fires is filling the valley. It doesn’t bode well for Glacier’s remaining glaciers—or for the 2021 fire season.

Fire towers can be on U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, or state lands. Some lookouts are paid, and some are volunteers, but all of us go through training organized by the Forest Service. Despite the ownership, the Forest Service is command central for all fires.

My tower, Numa, built in 1934, as well as others to the north, south, and west are survivors of a massive push in the 1920s and 30s to get eyes in the sky by putting a person at altitude with a grand view of a huge swath of forest.

There used to be thousands of lookout towers across the mountain West, but wild fire, deliberate fire, severe weather, and neglect have taken their toll. Luckily, northwestern Montana has a robust program to maintain remaining buildings and keep many staffed.

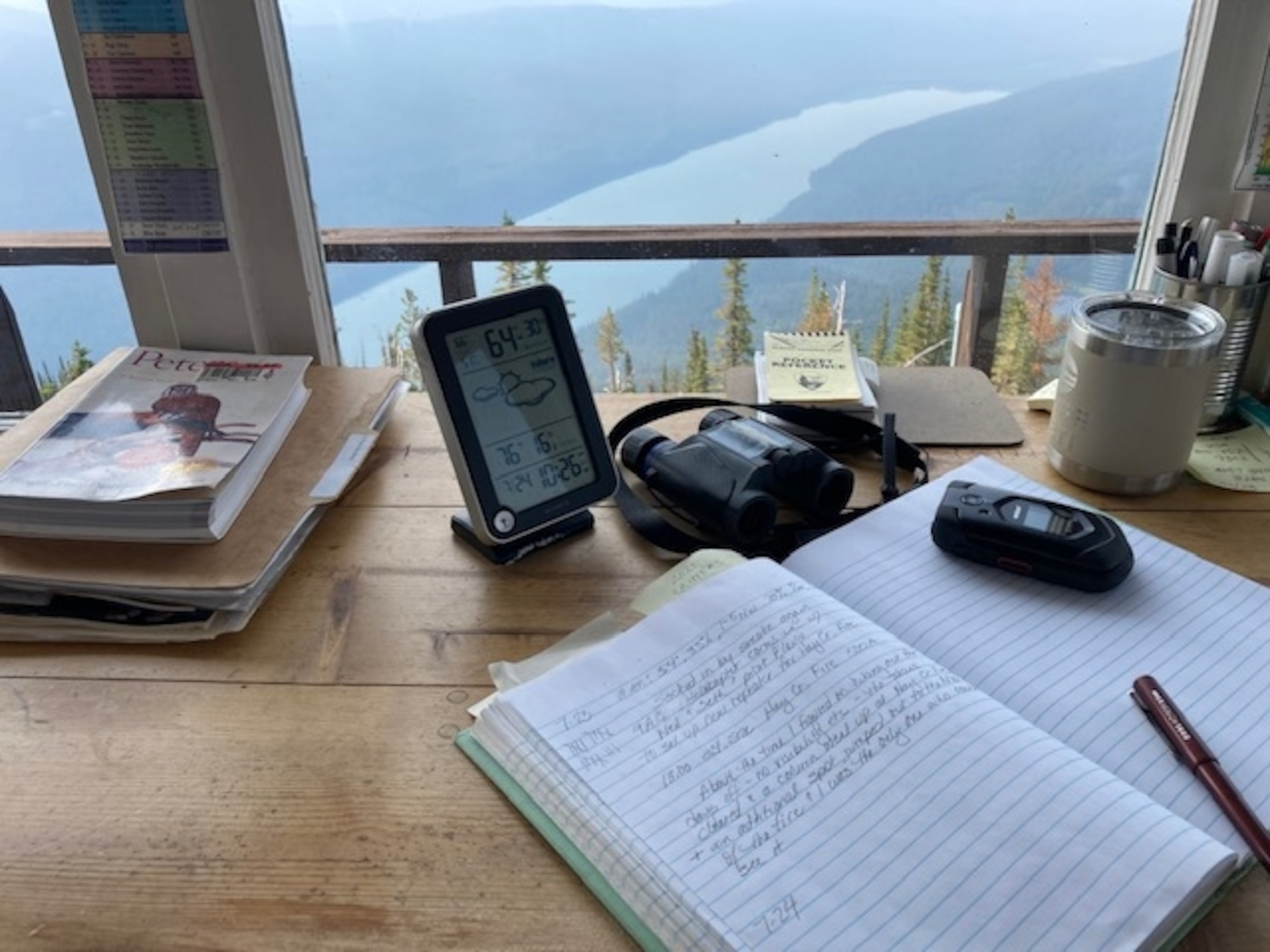

To be operational, a tower mostly needs a person who can hike to the building and abide his or her own company—after that, good binoculars, lots of maps, and a radio.

Yes, there are modern programs and satellites that can duplicate some of what a lookout does. But they don’t distinguish smoke decoys from actual smoke: road dust or water dogs (misty tendrils of vapor that often appear after a storm) or the play of light on a snag (dead tree) or unusual vegetation. They don’t monitor the site of a lightning strike for weeks waiting for the right conditions that allow a flare-up or maybe a full-fledged fire.

Sure, all the latest technology won’t chew up your boots if you leave them out on the deck the way a marmot will, but neither will it work if there’s a power outage or a software hack, or a satellite glitch. A real live analog fire lookout can watch and communicate in a simple and effective fashion.

July 1, 2021

The pack train arrives with mules Kate, Rance, and Tater loaded with 20 gallons of water (weighing @ 170 lbs) and the heavy duffels of my books and food, and they didn’t break any eggs. Cookies for the packer and carrots for the mules in appreciation.

July 21, 13:30

T-storms approach with lightning strikes, high winds, and some moisture. After the winds clear the air a little, smoke refills the valley and collapses my view-shed to a mere five miles. I have the existential job of looking for smoke inside of smoke.

For the past week, the air has smelled like a dirty, wet ashtray. Now there are heavy notes of charcoal added to the mix.

At 17:30, other lookouts are reporting a smoke column where I saw a down-strike of lightning today. The area is a hazy blur to me.

At 18:00, helicopter deployed. Initial fire assessment is 50 acres burned, buckets of water are dropped to arrest the fire’s push for the ridge.

August 3

From a single bolt of lightning, the Hay Creek Fire keeps chewing through the vegetation, up the various drying tributaries of the main drainage.

Throughout the day, depending on visibility, I may be able to discern new activity on the fire by columns of smoke and, if needed, alert ground crews. At night, orange glows flicker on and off as individual or groups of trees flare up.

As of this writing 13 days later, the fire has grown to 2,265 acres and is 5 percent contained.

It’s no small feat to make a fire conform to a plan, which for this one is to keep it from cresting the ridge and dropping into another drainage. So far, the helicopter bucket work and crew-lain miles of drip lines (hose to keep the ground moist)—and a bit of luck—have met the desired objectives.

Once a fire becomes established, incessant radio chatter and a sense of high alert replaces the quiet idyll of the earlier summer.

But even in bad fire years, there’s a rhythm to the days

Wake up to pre-dawn light.

In late June through early July, that means @ 4:30. By September, 6:30 is the norm. Without a doubt this is my favorite part of the day.

Make a steamy cup of coffee on my propane stove and take it outside to the most pleasant side of the narrow, wrap-around catwalk, just wide enough for a chair.

The lee side from the prevailing wind is a factor in this. The south side is preferable on quiet mornings because I can watch color progression to the east and also see the mountains and river valley to the west brighten with immense detail.

Listen to the birds, and insects, and, rarely but wonderfully, wolf howls or elk bugles.

If the wind isn’t too loud, I can hear the sound of water falling over rocks in the creek a thousand feet below.

Look out!

Really scrutinize the country looking for smoke columns. This is something I do off and on all day every day and is the main reason I’m up here. I use my naked eye and powerful binoculars to scan miles of countryside and the edges where ridgetops and mountains meet the sky in case something is just beyond my view-shed. I look out so much that oftentimes a smoke catches my eye simply because its foreignness makes it so obvious.

I have to be on guard for smoke decoys. No lookout wants to be responsible for sending a ground crew out on a useless chase for an unfounded fire.

At 10 a.m., starting at the northernmost lookout in the region and working south, each lookout radios to the Forest Service dispatch center in Kalispell the weather at his or her location. These data include temperature, relative humidity, wind direction and speed, cloud cover, precipitation amounts, visibility, and any lightning during the past 24 hours.

Look out!

Do usual lookout chores: scraping and painting this building that has been lashed by high winds, hailstones, and snow since last year’s work; washing windows; caulking windows, patching holes; sweeping floors; washing dishes. Monitor the radio for direct communications but also to relay for crews or individuals on the ground. Glacier park has lots of nooks and crevices with limited radio range and non-existent cell phone coverage.

Greet hikers.

Especially in a national park, sometime in the morning hikers start to roll in—for some, stagger in is a more apt description after the six miles and 3,000 feet of elevation gain. Many find my presence unexpected. There are questions to answer about the job, my living arrangements, wild animals, etc. My favorite first question: What books are you reading?

Yes, between times I can read (from War and Peace to the past 70 years of lookout journals), write, do crosswords, draw, bake cookies or bread, prepare a meal and eat it, have a solar shower, hike the hundred yards and the equivalent of five flights of stairs downhill to the outhouse and back up, and brew another cup of coffee.

Add an entry to the journal: “A day to really buff up my misanthropic tendencies… Had to put a stop to two boys (out of a group of six) trying to clock my resident golden-mantled ground squirrel in the head with a rock. Now three of the six are trying to flip the biggest rocks they can over the north ridge. Now four of the six are throwing the rocks that constitute the carefully constructed helicopter-landing pad over the edge. I SCREAM AT THEM TO STOP. These six boys would rival the glaciers for destructive force.”

Look out!

Everything is designed to look out. My tiny 14-foot-by-14-foot home has 19 large windows and one windowed door. All the furniture sits no higher than two feet, so none of the windows, none of the views are blocked. The exception is smack-dab in the center of the room where the hundred-year-old Osborne Fire Finder sits atop a three-and-a-half-foot platform. With a map in the center, and my tower in the center of the map, I can move the sights 360 degrees to pinpoint a smoke that can be relayed to headquarters by the azimuth reading.

The distance from the tower can be a trickier number. Ideally, another lookout will be able to see the same smoke, and, with an additional azimuth reading, there will be two lines that meet at the fire’s location. But conditions are not always ideal. This is where knowledge of the area’s drainages and ridges and roads is invaluable.

The official working day ends at 4:30 p.m. This means I’m free to take a walk, explore the area more closely, pick huckleberries, examine rocks, plants, and landforms. I know where on the trail I will be scolded by the nesting juncos, the talus field where the pikas have a colony. The grand views of the lookout are wonderful, but I find it important to shift my focus to a more intimate scale for part of the day.

Lightning storm!

Any time of the day or night, a lookout is on duty when a storm rolls through. Lightning strikes are a huge cause of wildfires in the West. During a storm, I’m relatively safe in my tower because of the grounding wires that run from the roof on all sides of the cabin. There is also a wooden stool with glass insulators on the legs inside the tower where I can stand in case any lightning comes inside the building.

But a storm can be a front-row seat to exciting chaos. Lightning can start fires immediately, usually from hitting a dry snag and igniting it. Flames may be visible from multiple locations in a very short time, requiring a lookout to prioritize the most worrisome; some will die out because of rain or lack of fuel; others, like the Hay Creek Fire, hit the right conditions and grow larger. But some strikes smolder, undetectable from a distance, waiting days or weeks for conditions to favor an eruption of flames.

Watch the sunset.

This is usually a long-drawn-out process with stunning color and light changes. If I don’t think it’s a show worth watching, I should probably find another job.

Despite living in the ultimate tiny house, with lots of windows, a wrap-around deck and killer views, lookout life is definitely not for everyone. The first summer that I was hired (in the 1970s), I was the third lookout of the season—the first two decided in a matter of days or weeks that it wasn’t what they imagined, or perhaps they never imagined how the isolation would affect them.

Three years later, the Forest Service relieved me of my duties when I was eight-and-a-half months pregnant. When I returned to the lookout the following year with my baby daughter, I read the journal entries of the person who’d replaced me for a month. They included references to the Rapture and drawings of double-headed axes and statements including, “They’re coming to get me!”

Karen Reeves who has loved maps and binoculars and camp craft since childhood is lucky enough to have found a professional outlet.