How Mars’s Close Encounters Helped Us Map the Red Planet

National Geographic’s archive has maps of Mars dating back to when some scientists still thought there might be Martian-made canals on its surface.

In just a few days, Mars will come within 36 million miles of Earth, closer than it has been for 15 years. As the red planet nears, we’re looking back at National Geographic’s cartographic encounters with one of Earth’s closest neighbors.

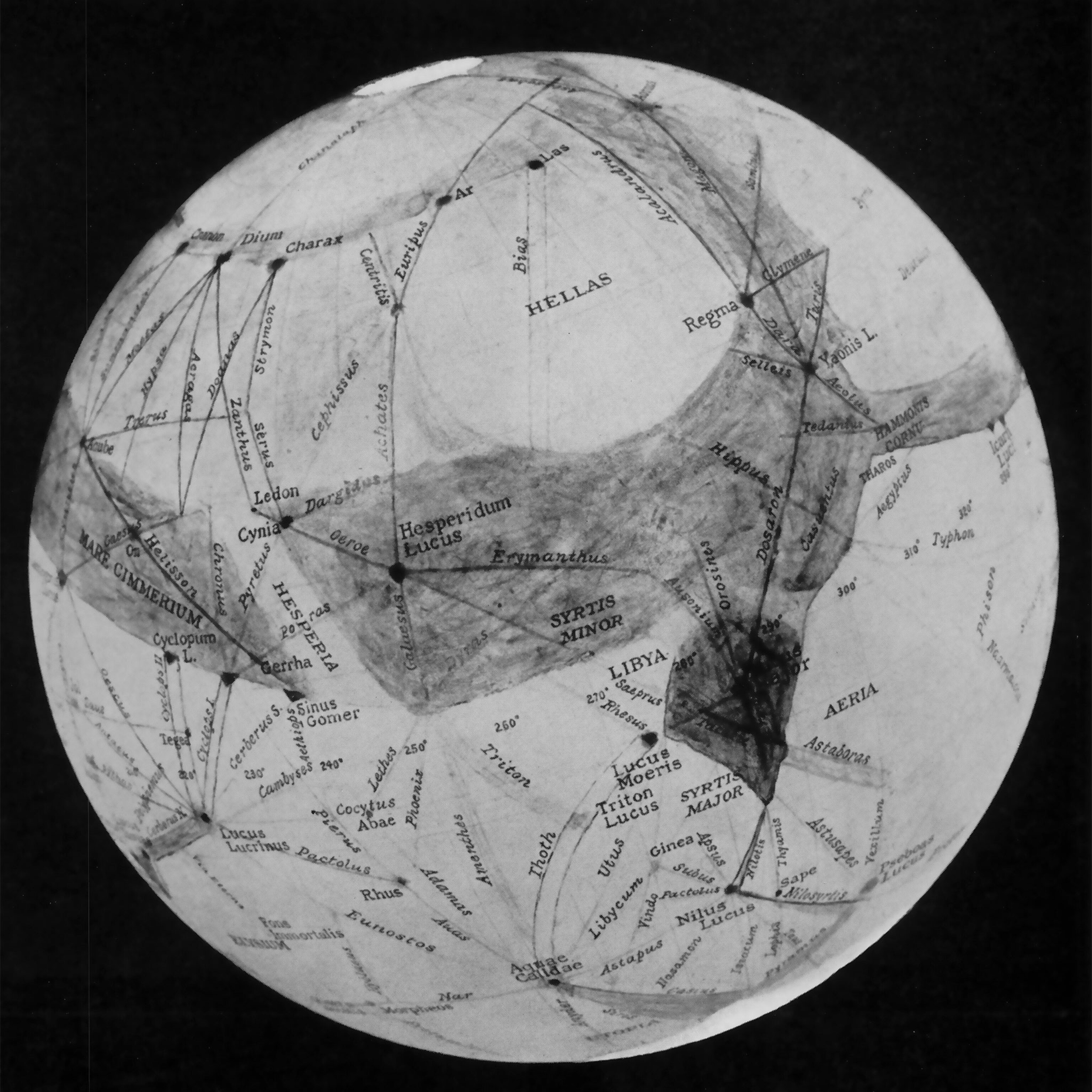

The first map of Mars to appear in National Geographic magazine was inspired by another close approach of the planet in 1954. To get a prime view of the event, astronomers from the Lowell Observatory in Arizona took a trek to South Africa that was sponsored in part by the National Geographic Society. An account of the excursion appeared in the September 1955 issue. It was accompanied by a half-century-old, hand-drawn chart of the Martian surface by Percival Lowell, an American astronomer who founded the Arizona observatory in 1894 largely because of his interest in Mars.

Lowell’s map offered a rendering of the idea he championed that dark lines visible on the planet’s surface were evidence of canals built by intelligent beings, and his map plotted the supposed canals. The story text, written by one of Lowell’s disciples, Earl Slipher, notes that many astronomers doubted the dark lines actually existed because they themselves hadn’t witnessed them during their observations. But he claims that some of the photographs he took during the 1954 approach clearly show the Thoth Canal. “It stands out with an intensity and size rivaling almost any markings on the face of Mars,” he wrote.

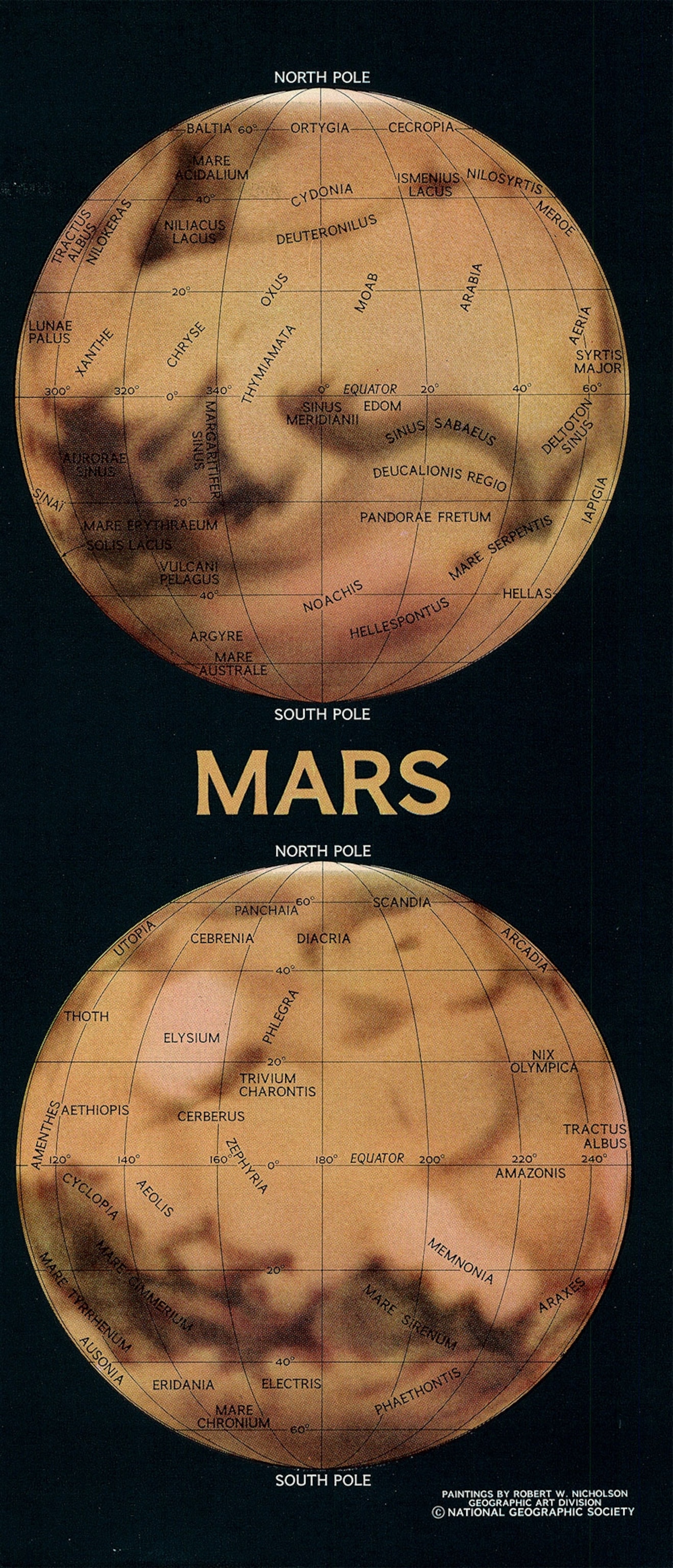

In March 1964, NASA launched the Mariner IV spacecraft to capitalize on another close approach of Mars to Earth, poised to happen in 1965. The canal theory was finally put to rest when the spacecraft made the first successful flyby of the planet in June 1965 and took the first-ever photographs of another planet from space. In an article for the December 1967 issue, Carl Sagan wrote that he interpreted the supposed canals to be ridges “comparable to ocean ridges and seamounts that lace the ocean bottoms on Earth.”

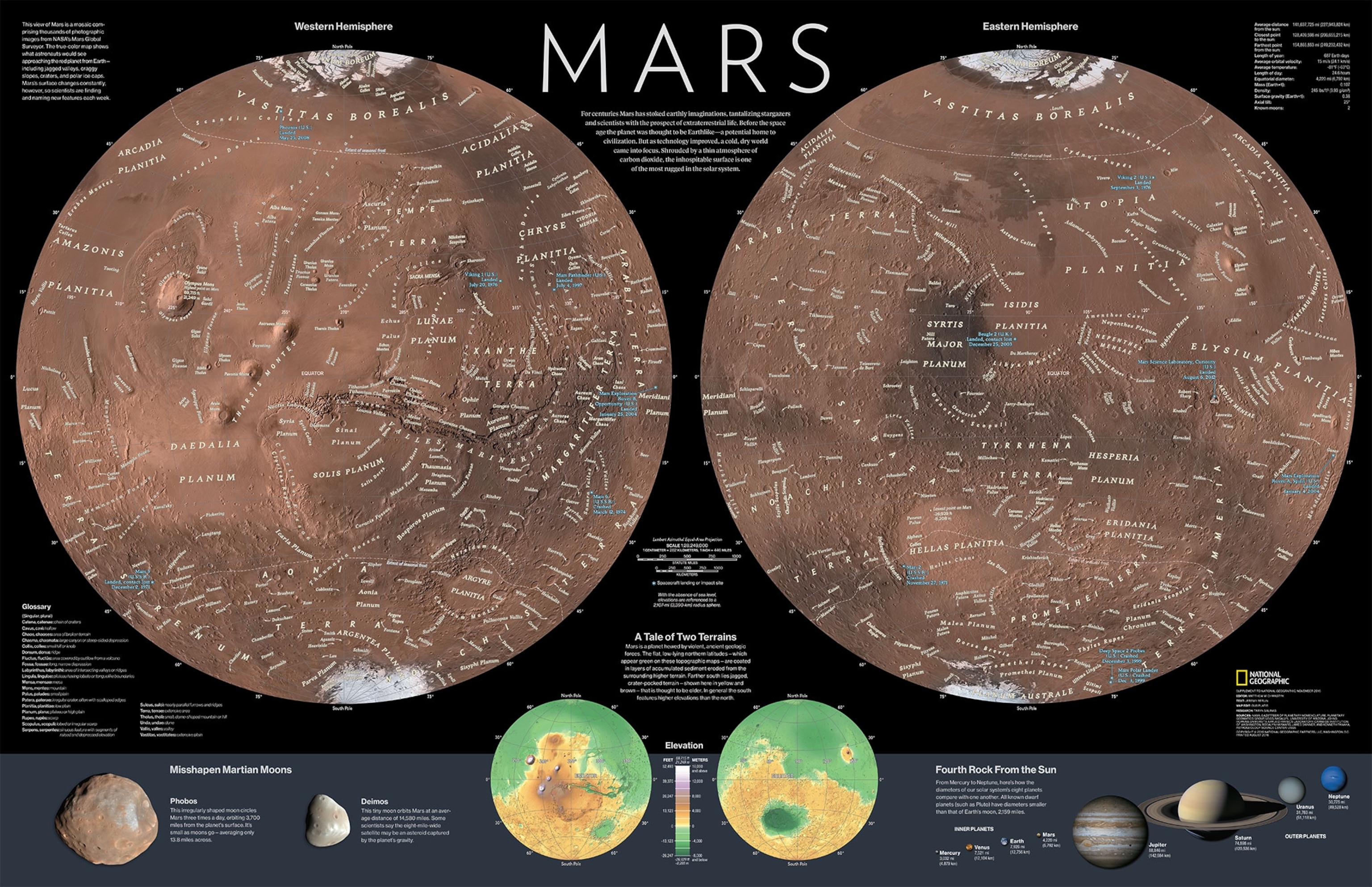

Sagan’s article is accompanied by the first map of Mars made by National Geographic cartographers to appear in the magazine. The planet is shown in two hemispheres, similar to how astronomers had historically presented their maps of the planet. The design of the 1967 map inspired a supplement—a poster-size pull-out map—designed for the November 2016 issue by Matt Chwastyk, a senior graphics editor and the chief space cartographer at National Geographic.

“Those old maps are really well thought out and well researched and every detail was pondered before it was actually put to paper,” Chwastyk says. “Sometimes we get little flourishes that we add to our maps from those old maps that are really great sources of inspiration.”

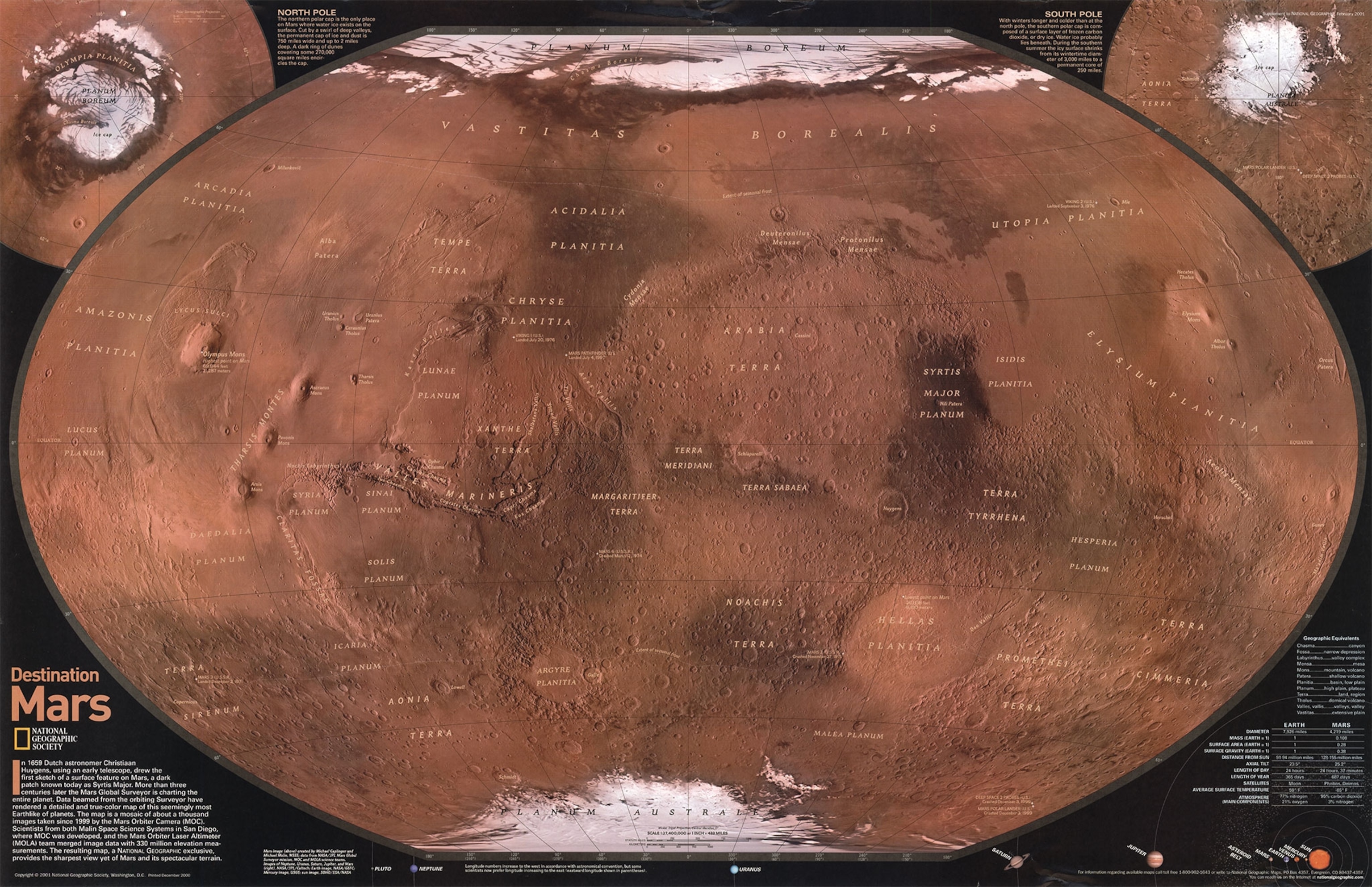

Using two hemispheres is also typical of most lunar maps, because the moon has a near side that always faces Earth and a far side that faces away, creating a natural way to split up the sphere. The last Mars supplement prior to 2016, published with the February 2001 issue, had used the same style National Geographic uses for most maps of Earth, known as the Winkel Tripel projection, which curves the northern and southern parts of the map toward the poles.

But for his 2016 map, Chwastyk opted to break the map out into two hemispheres. “I wanted to give it more of a planetary feel,” he says. An upcoming moon pull-out supplement will be designed in a similar style, making a nice pair of maps to hang together on the wall.

Though Chwastyk had a lot of data to work with for the 2016 map from several past Mars missions, including the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Global Surveyor, there were still details that were challenging to pin down. In researching the official highest and lowest points on the planet, Chwastyk got a half dozen different answers from various experts and NASA web pages, “which is interesting considering Mars is better mapped than Earth, at least in geophysical terms,” he says.

National Geographic continues to keep its eye on Mars, and Chwastyk is currently at work on an upcoming map of the planet for the November issue of the magazine, timed to coincide with the arrival at Mars of NASA’s latest robotic lander, Insight.

The map imagines what the planet might have looked like 3.8 billion years ago. After consulting with scientists, Chwastyk created a watery planet with oceans and greyish-green hued continents. “It's totally hypothetical, so there's a little bit more leeway,” Chwastyk says. “But we want to make sure we're not creating science fiction.”

Stay tuned for more stories about National Geographic’s editorial map archive here on All Over the Map. And see a different map from the archive every day by following @NatGeoMaps on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.