Meet Raghava KK: Welcome to the New India

India is a country of contrasts. Farmers walk their cows along the same roads that people drive fancy sports cars. While some people continue to observe 5,000-year-old traditions, a few blocks away scientists plot how to put a rover on Mars. Young people who are the products of arranged marriages are crafting new ideas for businesses that give people exactly what they want.

It makes it hard to know the country’s true identity or tell its story. But India is dying to tell its story, and in Bangalore, a city at the crux of the contrast, is one of its anointed storytellers.

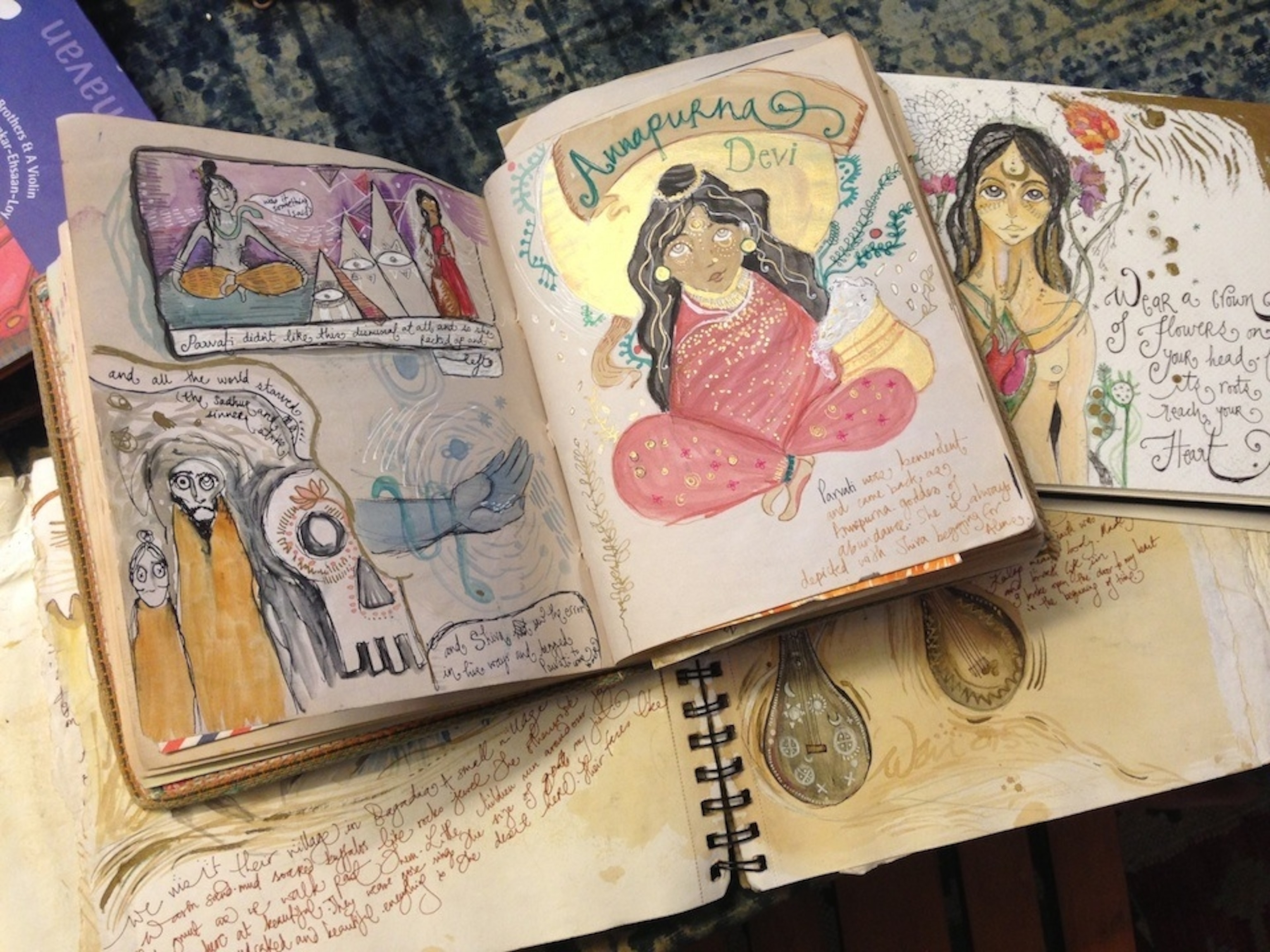

Meet Raghava KK, a 30-something who embodies the contrast and is dying to tell his country’s story. He has an energy that’s hard to match, a constant get-up-and-go that has made him one of India’s most dynamic spokespeople. In a large house in Bangalore’s Jayamahal Extension, Raghava explains who he is. Foremost, he’s an artist, who paints canvases that sell all over the world for as much as $250,000. He’s an activist, speaking out on social issues that push people to find their personal compass. He’s a mentor, helping kids learn hacks—the tech term for easier ways to do things—by animating classrooms and simplifying complex ideas. At one school in Bangalore, he works with kids with autism, helping them master certain motor skills with murals they can interact with and cartoon caricatures that mimic human actions. With all his spare time, he’s a businessman trying to get a start-up off the ground.

And yet, he says one morning while sitting next to a chalkboard wall that he had free-associated ideas onto, “maybe I’m none of those things. I don’t even think I’m an artist. Maybe I’m more of an…” he trails off, looking out the window for the right word. “Maybe I’m just an explorer.”

Fine. Call Raghava KK (who’s last name is traditional Indian and much longer) an explorer. Others have. In fact, the artist/businessman/activist/hacker (those last two he has morphed into “hactivist”) was named a Emerging Explorer from National Geographic this year, a title granted to up-and-coming thinkers leading their fields, or their countries. He loves the title, he says, because of the potential it conveys. His best work is still ahead.

Six hundred million people—half of India’s billion-plus population—are under 35. It’s the largest population of young people anywhere in the world, and as the country continues to rapidly industrialize, demographers have pointed to India as a case study of how a country can survive or fail depending on whether it opens social and political barriers for young people who want to create things.

“The next five years will make or break India,” says Lakshmi Pratury, the head curator of India’s annual Innovation and Knowledge (INK) conference, an Indian version of TED. “If we don’t give young people the opportunities to pursue their ideas, we’ll miss the boat.”

Some people in India used to think in terms of shortage. Now they think about abundance. The U.S. is an example, Raghava explains, of what happens when you eliminate roadblocks and let people pursue their ideas. Silicon Valley is the model for Bangalore’s tech scene. Hollywood, the inspiration of its movie-making industry. New York is the mold of every kind of diversity. Last year when Raghava met President Obama in Washington he told him, “You have a melting pot here, but in India, we still have a buffet.” Obama laughed.

India has its challenges. The rupee is still weak against the dollar. Over the next 30 years, the country will need to create 10 million new jobs for its bulging population. It might, however, also have a hard-fought competitive advantage. Packed cities of 10 million or more are likely to become the norm around the world. New York will hit that benchmark in the mid 2020s, as will London. “We have a 60-year head start living in these conditions, where people and knowledge are fragmented,” he said. The translation: India has already figured out how to run amidst urban chaos.

One afternoon, while driving around town, I asked Raghava if he could summarize the “new India,” just enough to make sure I fully understood the nebulous idea.

He thought for a long time. “You know, it’s difficult to come up with an elevator pitch for what this country is becoming. How do you form one single identity in one sentence when you have so many dismembered parts? But think of it like this. We don’t want our heroes to be billionaires or politicians, we want to celebrate individual spirit.”

I laughed and told him that only slightly clarified the concept.

He had an idea. “Let’s have a party tonight,” he said. He made a few phone calls and mobilized about 25 friends with less than two hours notice to come meet a strange reporter from America. It seemed like Raghava was lining up his close friends to come give good testimony about his work. But true to the man of contrasts, it was the opposite. He asked everyone to go around the room pitch his or her ideas. “Just explain what you’re working on.”

One by one, vibrant projects piled up. One guy was developing a new type of 3-D printer that could print chocolate. Someone else was trying to turn old shipping containers into movable stadiums. A 22-year-old woman described how she was helping to push the women’s’ rights movement in India, a pursuit with risks in light of several episodes of sexual assaults, including several in Delhi and Kerala last year. There were local ideas: one enthusiastic idealist wanted to bring accountability to Bangalore’s sometimes unsafe public taxi system. And global ones too: a savvy entrepreneur had built a tech company that let people in rural areas use search engines via text (the most common query topic: sex).

The group spoke with irreverence, willing to pursue their ideas despite what anyone else thought, unmoved by a sluggish economy or their political leaders or a culture often rooted in the past. After a few hours, the American reporter excused himself, jet-lagged and spent. While in the next room, India’s new creative class partied unfatigued much longer into the night.