6 Female Artists Who Turned Modern Art On Its Head

These often overlooked women helped shape modern art around the world.

Despite their mastery and innovation of the arts, the visionary women of the modern art world are rarely discussed in mainstream histories.

“When you look at the way most art history [of the modernist era] has been written, if these women are mentioned, they’re mentioned in passing,” says Deborah Gaston, the director of education and digital engagement at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. “A lot of them are also involved with other artists who are part of that circle. It continues that narrative of them being followers instead of creative innovators in their own right.”

Here are six often overlooked women who had major impacts on the modern art scene.

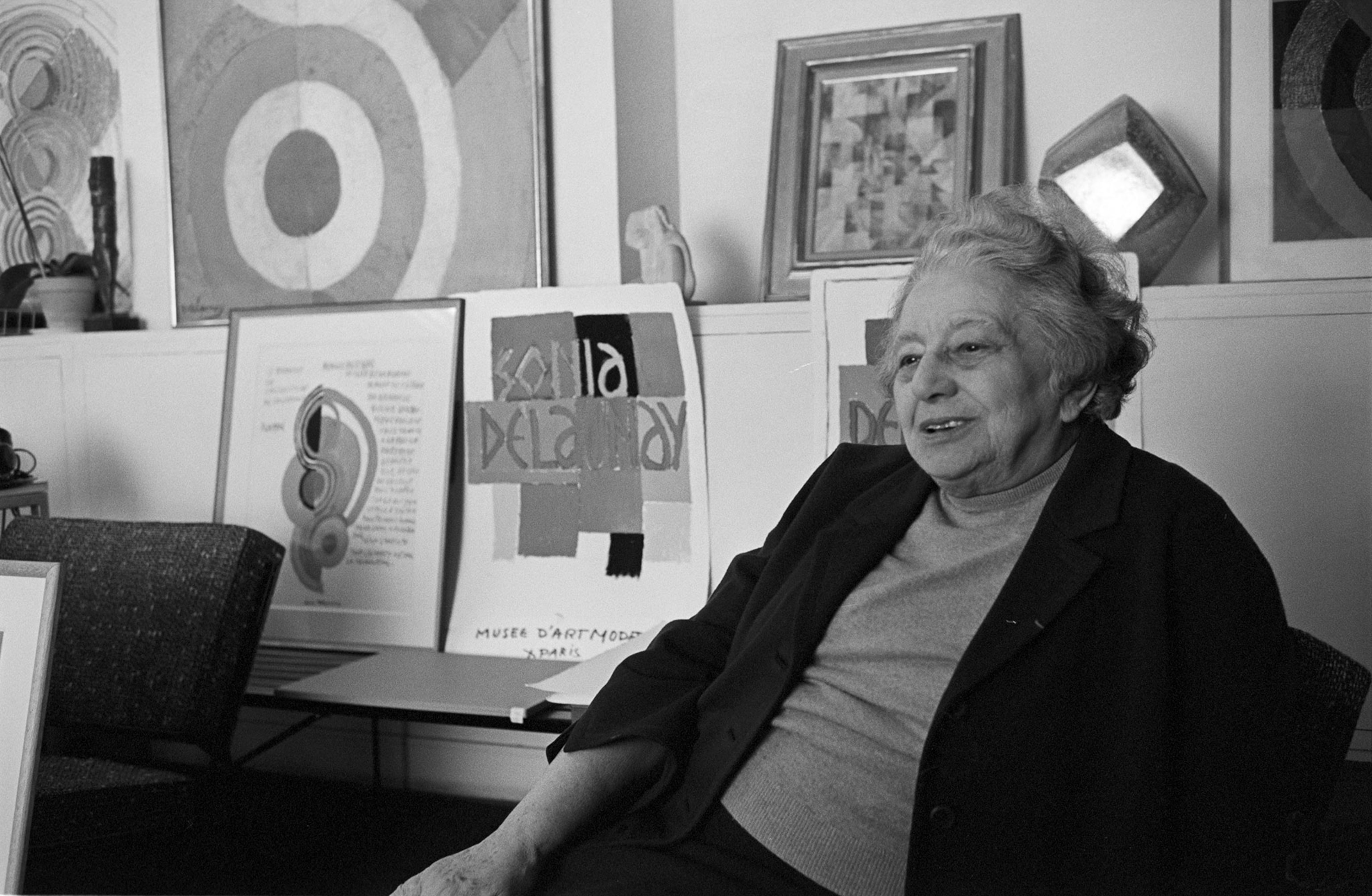

Sonia Delaunay: The Mother of Orphism

Born in Ukraine on November 14, 1885, Sara Élievna Stern grew up using the nickname “Sonia.” Delaunay studied art in Germany and France, where she later married art dealer Wilhelm Uhde in Paris. The union kept her family from forcing her to come home and also served as a cover for Uhde’s homosexuality.

In addition to her traditional art schooling, Delaunay was a powerful force in the world of decorative arts, with a particular talent for textiles and interior design. After her amicable divorce from Uhde and marriage to French painter Robert Delaunay in November 1910, the Delaunays spearheaded Orphism, an abstract, vibrant, variation of Cubist and Futurist art.

“I always changed everything around me,” Delaunay famously said. “I made my first white walls so our paintings would look better. I designed my furniture; I have done everything. I have lived my art.”

In 1964, Sonia Delaunay became the first living female artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre in Paris.

Marie Laurencin: The Feminine Cubist

Marie Laurencin was born in Paris on October 31, 1883. She was raised by her mother and studied art alongside Georges Braque, who would go on to help develop the Cubism movement.

Laurencin created paintings, watercolors, drawings, and prints. She’s one of few female Cubist painters, along with Delaunay, and developed a unique approach to abstraction. The pastel hues and willowy figures in her works lend them a feminine aesthetic. She painted portraits of Parisian celebrities, featured animals in her work, and produced theater sets.

In 1983, the Musée Marie Laurencin opened in Japan, becoming the only specialty art museum in the world to focus on a female painter. The museum houses more than 600 of her works in its archive.

Aleksandra Exter: The Art School Rebel

Also known as Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Ekster, Aleksandra Exter was born in Białystok, Poland to a wealthy Belarusian family on January 6, 1882. During her private education, she studied languages, music, and art, and she eventually rose to international fame in the European art scene.

At Kiev Art School, Exter mixed and mingled with other artists who would resurface in Russian New Art. In 1908, she married a Kiev-based lawyer and the two became prominent cultural and intellectual characters. They moved to Paris, where Exter briefly studied at Académie de la Grande-Chaumière until she was expelled for rebelling against the institution’s artistic vision.

Exter’s style became increasingly radical and avant-garde over time. She cycled through Impressionism, Cubism, Cubo-Futurism, and nonobjective art with abstract paintings of cityscapes, geometric forms, and still lifes. Her work is dynamic, and in addition to her exhibitions, the multitalented artist excelled in theatrical work and book illustrations.

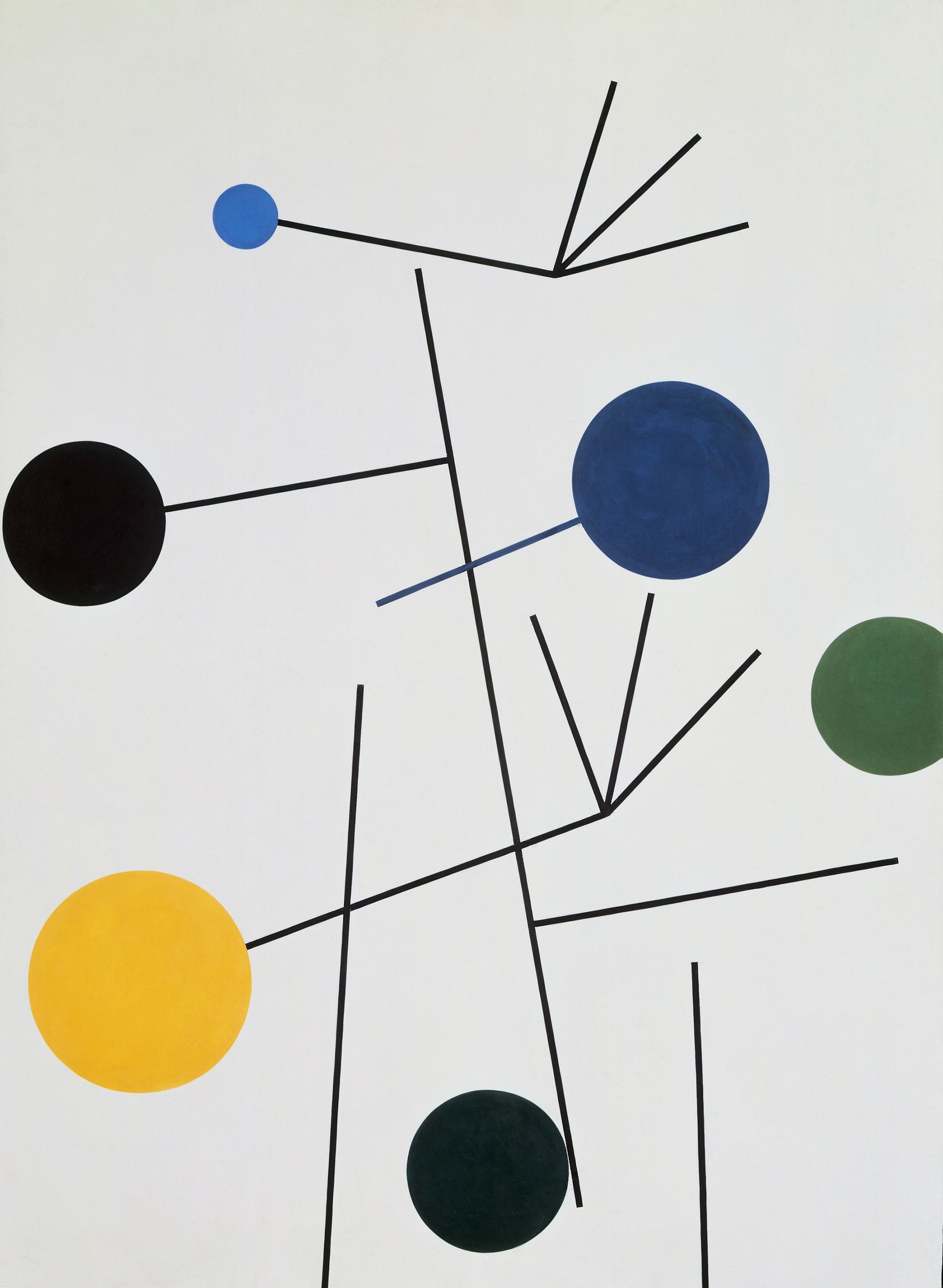

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: The Unbound Visionary

Sophie Henriette Gertrude Taeuber was born in Davos, Switzerland, on January 19, 1889. She studied drawing at the School of Applied Arts in Saint Gallen and then went to Germany to study textile design. She also studied weaving, beadwork, and dance.

Taeuber-Arp was influential in Zurich’s Café Voltaire, and it wasn’t until 1928 that she moved to the Paris area. Her work as a painter, sculptor, and architect—not to mention an accomplished furniture and interior designer—dissected boundaries between different genres of art.

She embraced modernism and Dada art, and she even created costumes and puppets for Dada performances. She collaborated with other artists like her husband Hans to produce shows, dances, writings, and fine art works.

As a nod to Taeuber-Arp’s legacy, the Swiss government redesigned the 50 franc note in 1995 to include her portrait.

Natalia Goncharova: The Experimental Innovator

On June 21, 1881, Natalia Goncharova was born into an elite family in Nagaevo, Russia. She began her studies at the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture in 1901, drawing inspiration from the Impressionists—Auguste Rodin in particular.

As a painter, Goncharova’s work has notes of the sacred mixed with the profane. Some of her art includes rural Russian laborers performing repetitive, everyday tasks, but her traditional style lends itself to religious interpretation. Goncharova’s formal art training ended in 1909 when she was expelled from the Moscow Institute for not paying tuition.

Goncharova also worked in textiles and, with her husband and fellow artist Mikhail Larionov, explored Russian avant-garde styles that would lead to future art movements. Goncharova’s efforts in Rayonism and Futurism influenced her Russian contemporaries and were crucial in guiding future abstraction.

Tarsila do Amaral: The Revolutionary with Roots

Often known simply as Tarsila, do Amaral was born on September 1, 1886 in Capivari, Brazil to a wealthy family of coffee growers. Tarsila’s family supported her educational pursuits, encouraging her to attend school in Barcelona, where she first picked up an interest in art.

Tarsila began her formal art education in 1916, studying sculpture, drawing, and painting, but Brazil’s conservative art world and lack of creative resources limited her exposure. Trips to Paris helped to broaden her artistic horizons, and she eventually became part the Grupo dos Cinco, a movement of artists who actively promoted Brazilian culture without employing traditional European styles.

“I want to be the painter of my country,” Tarsila wrote in 1923. Her style of blending local Brazilian icons with avant-garde aesthetics helped shape Brazil’s modern art, and her legacy remains today.