Riffing with Mulatu Astatke, the king of Swinging Addis

His legendary jazz fused American style and Cuban rhythms with East Africa’s pentatonic scales. Now, at age 82, Mulatu Astatke wants to turn the spotlight on the tribal musicians of his beloved Ethiopia.

At age 82, Mulatu Astatke has one subject he wants to talk about. Never mind the many things one might be anxious to ask the jazz giant: How was it that he came to invent the world-changing music known as Ethio-jazz? What was it like to be part of the jazz scene in 1960s New York, or in Ethiopia’s capital during the creatively fertile period known as Swinging Addis? What were the long years of the Derg, the military junta that gripped his country through the 1970s and 1980s, like? What does he see as the future of world music, a category he helped create?

From any of these lines of inquiry, Mulatu is sure to politely but reliably steer the conversation to the one subject he wants to discuss: the tribal musicians of Ethiopia, who he calls “the bush people,” and what he sees as their underappreciated contributions to the history of music—not least, and perhaps most pointedly, his own.

“As an African, it is my duty to give the respect to the geniuses of Africa,” he says, his voice hoarse and low. “That’s the whole thing.”

So be it. The man has earned the right to talk about what he wants.

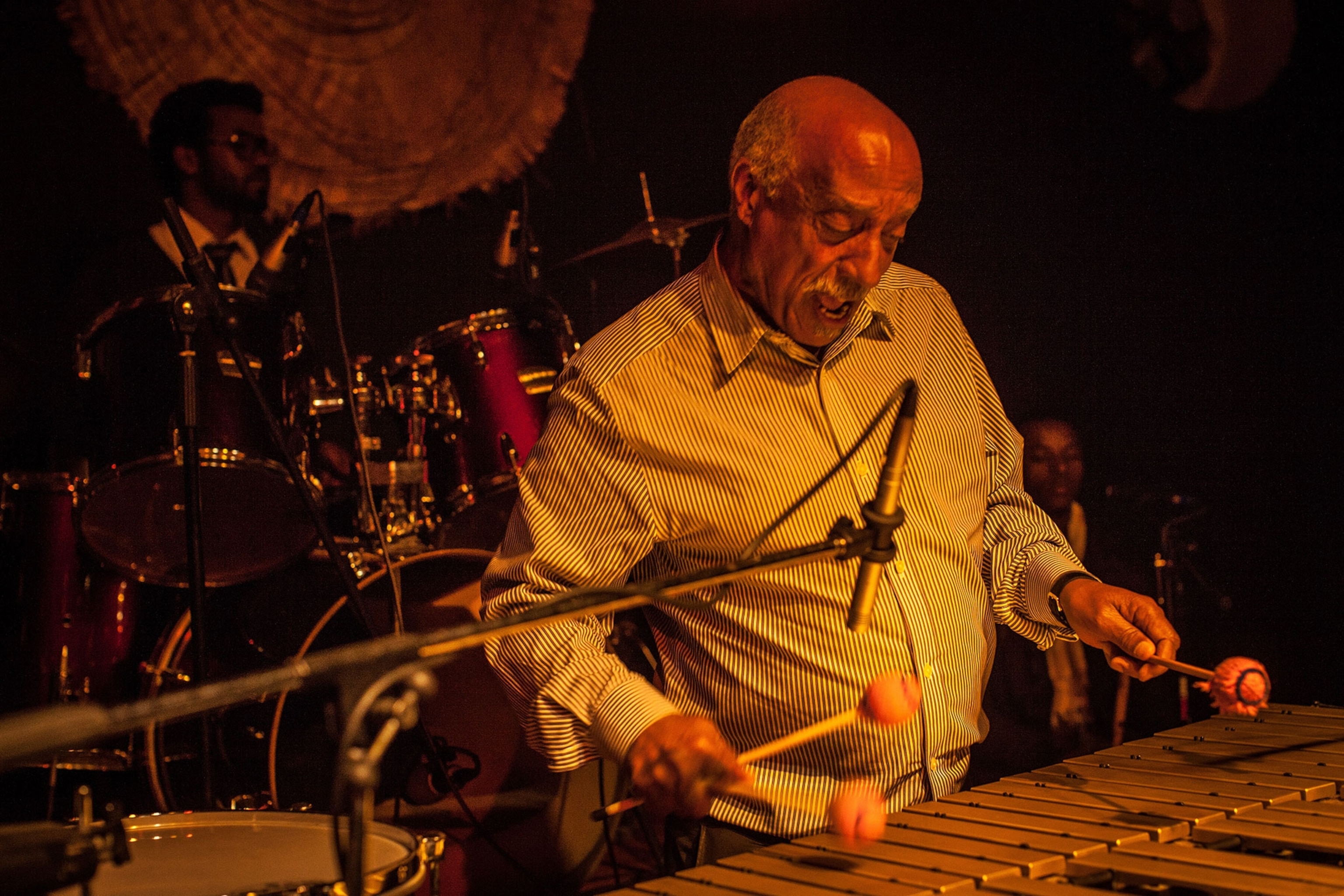

Mulatu is sitting outside a hotel in Pisa, Italy, on a fall day, dressed in an overcoat, despite the unseasonable warmth. (In Ethiopian tradition, people are referred to by their first names; Mulatu, in turn, calls everybody Chief.) That night, he and his band will play in nearby Cascina, a stop on what has been billed as his final European tour. It was occasioned by his most recent album, Mulatu Plays Mulatu, which revisits some of his most famous compositions (one of them, yes, also named “Mulatu”).

(A mecca for rap has emerged from the birthplace of jazz and blues)

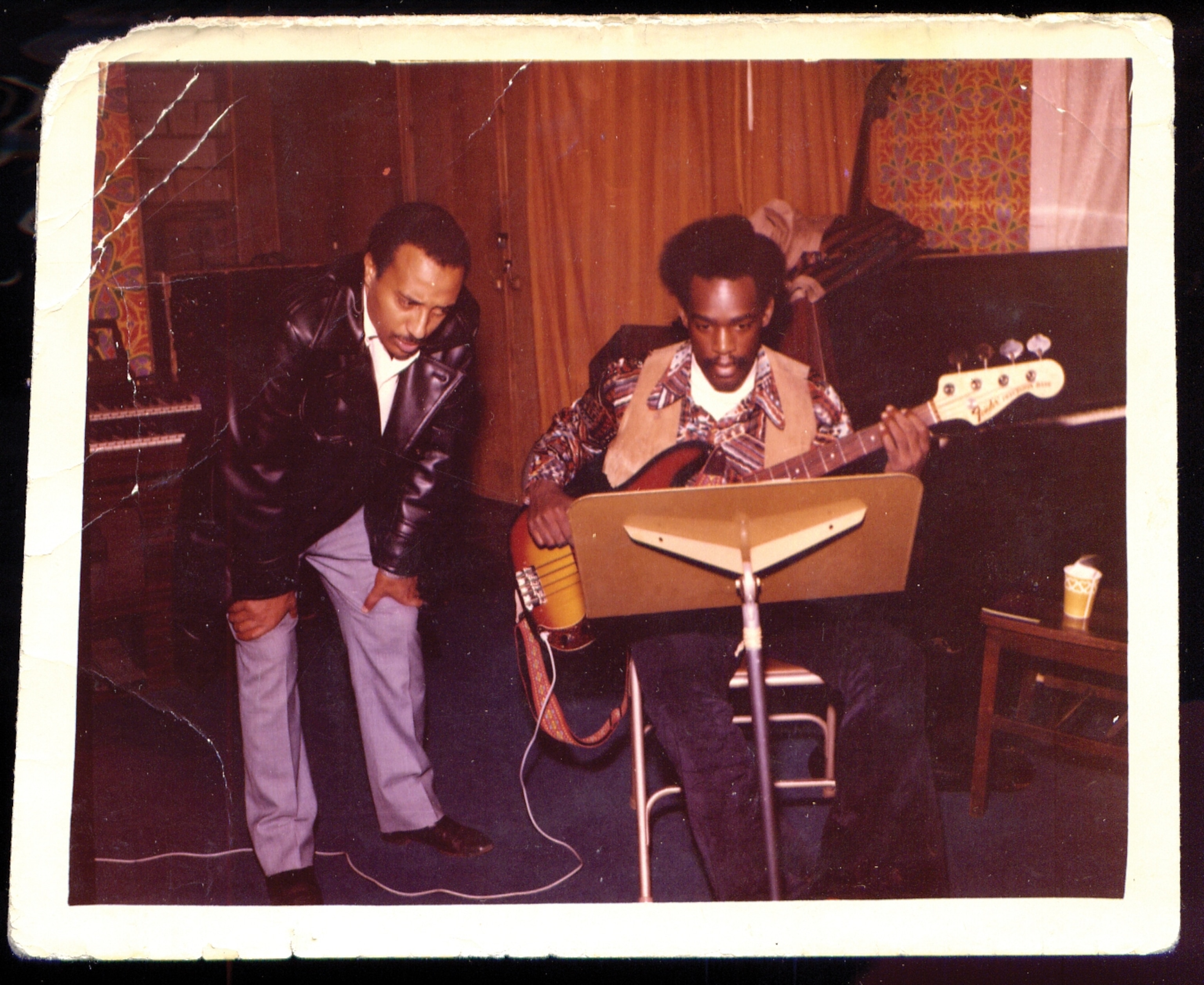

Starting in the early 1970s, Mulatu released an epochal series of albums that fused American jazz and Cuban rhythms with the pentatonic scales based around the four "modes" of his native Ethiopia. Ethio-jazz, as Mulatu named his creation, not only expanded the definition of what jazz could be but changed how the world listened. It implicitly connected the West with a diverse and deep tradition, halfway across the world, that few knew anything about.

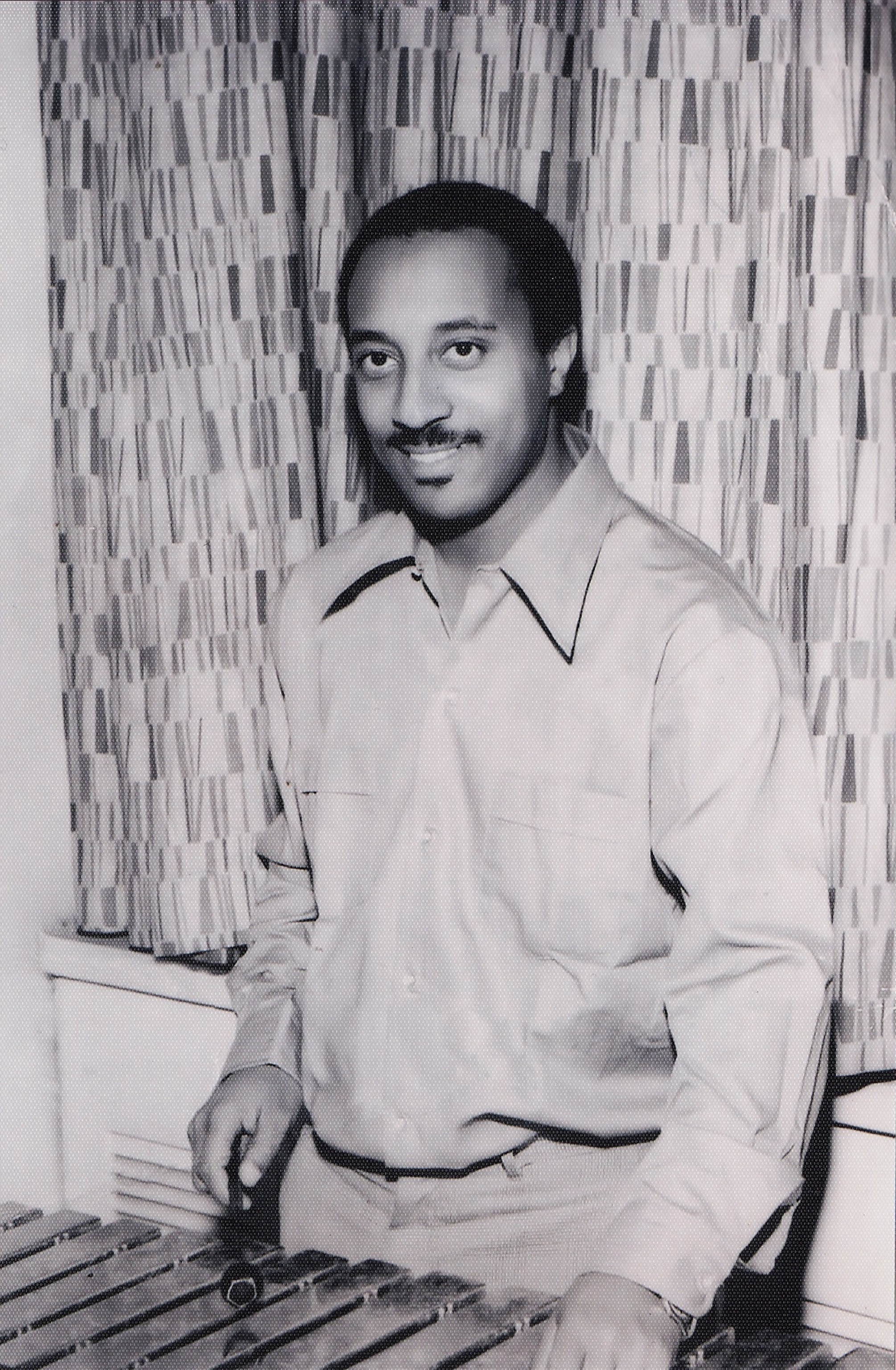

Ethio-jazz’s seed had been planted at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, where Mulatu arrived in 1963 as the prestigious school’s first African student. This was after a stint at a private high school in North Wales, where he was told that, rather than engineering, which he had arrived intending to concentrate on, his future might be in music. Mulatu still expresses surprise that the teachers there took the time to see their young foreign student so clearly.

At Berklee, he remembers sitting in class, learning about such figures as Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, and thinking, “How come I don’t become like this? How come I don’t become like these big famous people?” he says. To do so, he realized, “I had to learn how to be myself.”

There had been interactions between modern Western and Ethiopian music before, going back at least to Emperor Haile Selassie’s fascination with military bands, but until Mulatu, they had never been so deliberately realized and sparklingly constructed. More than half a century later, the music remains impossibly alluring. It is propulsive, melancholy, and mysterious—all the traits that one assumes spurred Jim Jarmusch to use it on the soundtrack to his 2005 film Broken Flowers. Thanks to that movie, and the multivolume French compilation of Ethiopian music, Éthiopiques, Mulatu has become embedded in our sonic landscape, both literally (if you’ve eaten in restaurants the past two decades, you’ve almost certainly heard his songs in the background) and through his influence on funk, hip-hop, and other genres. As Mulatu puts it: “I took the four modes of Ethiopia and, on top of them, I built the world.”

One thing those early records lacked, though, was an emphasis on the traditional instruments and musicians on which the “Ethio” part of Ethio-jazz was based. The omission seems to have haunted Mulatu all these years. “Always, these people were on my mind,” he says.

In this way, Mulatu Plays Mulatu feels like a kind of atonement, or at least an attempt to repay a perceived debt. Recorded in London and Addis Ababa, the album reinterprets Mulatu’s classics, this time integrating and highlighting traditional instruments. These include the lyrelike krar, the single-stringed masenqo, and the conical drum known as the kebero. Coupled with the playing of the tight band of young, mostly white, British players with whom Mulatu has long toured, the effect is to expand his canon in two directions—toward an ancient past and a dynamic future.

“I think it was a life’s work for him,” says Dexter Story, the Los Angeles–based musician and ethnomusicologist who produced the album. “He was like, ‘I’ve got to do this. I’ve got to put these things together in a special way.’”

That urgency shows itself in Mulatu’s single-mindedness in conversation. Spend a little time with Mulatu and you may start to believe that all music bears some direct or indirect influence from his beloved bush people. Charlie Parker, he points out, is lauded for his innovative use of dominant-diminished scale in his solos, but the same scale is found among the Derashe people of southern Ethiopia. The cello, he insists, is equaled by the masenqo. Recently, he says, he has been working with an American musicologist to create software that would expand the number of notes available on traditional Ethiopian instruments, opening the possibility that, say, one could play Beethoven on the krar. His eyes light up at the possibility. “I can hear it! I can hear it!” he says.

“He is a dreamer,” says pianist Alexander Hawkins, who has played with Mulatu for over 15 years. And, of course, it was just such a leap of imagination that opened the world of Ethio-jazz in the first place.

Coming home from the show in Cascina later that night, Mulatu smiles thinking of the packed crowd and standing ovations. “I think I have a done a good job of spreading Ethio-jazz around the world. Now I can sleep,” he says.

But back at the hotel, before disappearing upstairs, he has one more thought, flashing a mischievous grin that indicates he’s aware he may have mentioned it once or twice before.

“Chief,” he says, “don’t forget the bush people.”