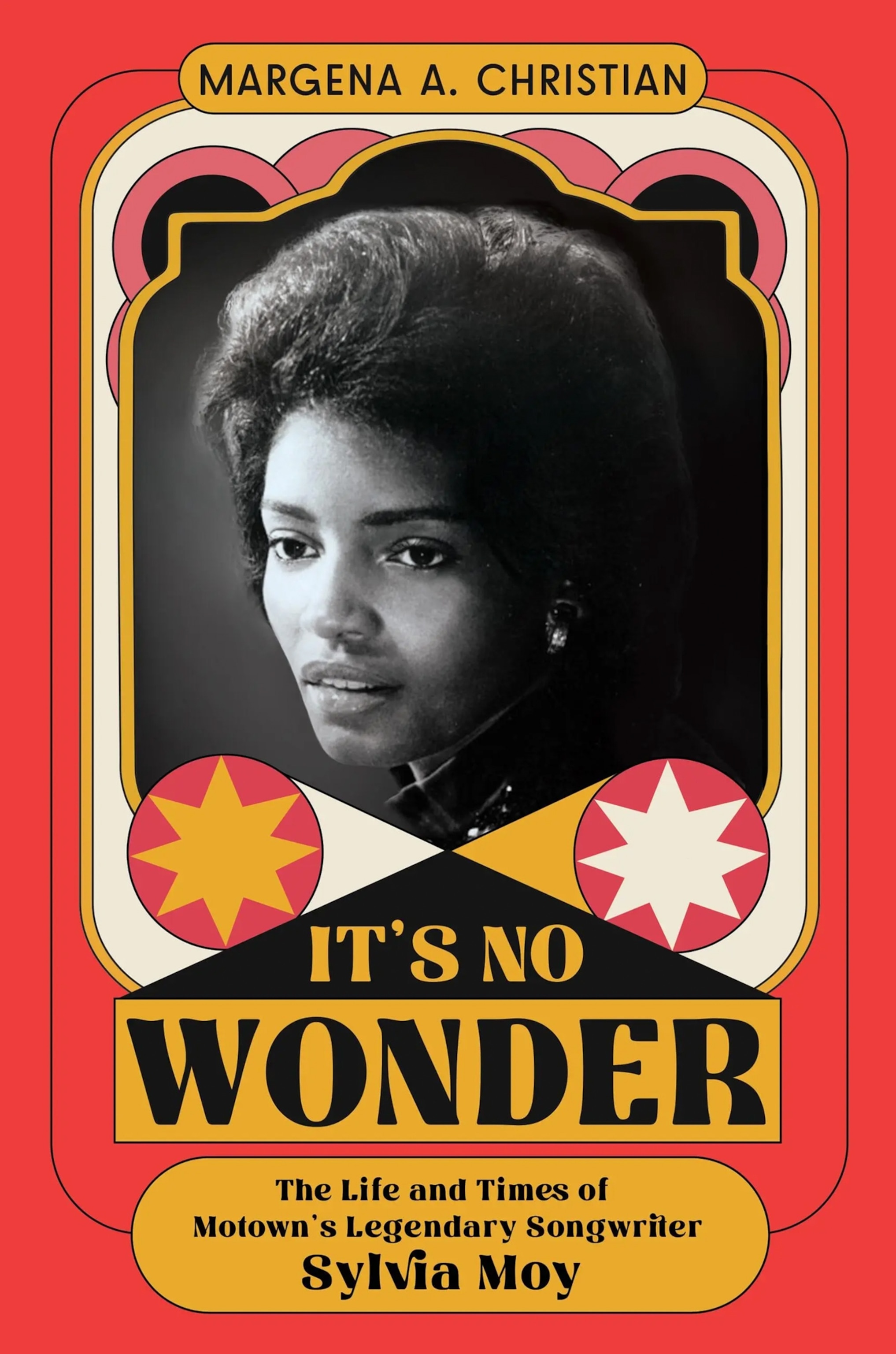

The female songwriter who saved Stevie Wonder's career

It's hard to fathom life today without the hit songs of Stevie Wonder. If it wasn't for Sylvia Moy, an unsung Motown powerhouse, we might never have gotten those tunes.

In 1963,“the Sound of Young America,” as Detroit-based Motown Records was known, was a source of unity in a deeply divided country. Appealing across racial barriers, a steady stream of crossover songs helped it become widely known as Hitsville U.S.A. From Mary Wells, Marvin Gaye and Martha & The Vandellas to The Miracles and The Marvelettes, the hits kept coming and its artists garnered recognition in mainstream American culture on record charts and television shows.

Even the label’s youngest musician, 13-year-old Little Stevie Wonder, scored big that year with a harmonica-driven groove called “Fingertips-Pt 2.”

Performed in Chicago at the Regal Theater a year earlier, the single reached number one, and when the album, Recorded Live: The 12 Year Old Genius, was released, it topped the charts, too, allowing the youngster to stay in alignment with his hit making colleagues. When Wonder was signed to the label in 1961, Motown’s president and founder, Berry Gordy, made it no secret that he was more impressed with the blind kid’s harmonica skills instead of his singing.

It seemed that others felt the same way. As quickly as Wonder landed atop the charts, follow-up efforts, including Tribute to Uncle Ray and With a Song in My Heart, failed miserably. While some at Motown surmised that the child seemed to have been on his way to becoming a one-hit wonder, Gordy remained encouraging. Despite doing just about everything to promote and expand the youngster’s audience—even having him appear in the popular beach party movies—Gordy’s best attempts were no match against puberty. Wonder’s voice began to change and the situation appeared hopeless. By 1965, after a three-year lull without another hit, Gordy really didn’t know what else to do with the teen.

Providentially, Sylvia Moy, the label’s first female in-house songwriter at the time, did.

An aspiring music teacher and singer looking to earn money for college, Moy arrived to Motown hoping to perform. The song stylist also could produce and play instruments, including piano, guitar, and drums.

She was discovered in 1964 singing at Detroit’s Caucus Club (the same place three years earlier where singer Barbra Streisand performed for the first time outside of New York) by Motown A&R Head William “Mickey” Stevenson and soul crooner Marvin Gaye. Stevenson suggested Moy audition at Motown.

He recalled her voice being impressive, but her skills as a songwriter stood out more with the two original tunes she performed during the audition. Since timing was everything and with the label’s skyrocketing success, cranking out hit songs like an automobile assembly line, Moy was signed as the label’s first female in-house songwriter.

Though women songwriters existed at Motown before—notably Janie Bradford and Raynoma Gordy Singleton, Berry Gordy’s second wife who also did production-vocal arrangement and played a multitude of instruments—Moy was in her own lane as the first to be signed and having to go up against males, consistently, consecutively, and simultaneously, in the extremely competitive Motown environment.

Reporting directly to Stevenson, Moy was thrown in the mix with songwriting heavyweights like the Holland-Dozier-Holland team, Smokey Robinson, and Norman Whitfield. While Moy stood out in her abilities, like other females across the music industry at large, structural sexism and power dynamics kept her efforts and accomplishments concealed.

This was the Sixties, a time when women songwriters were expected to partner with men for credit, and even then nothing was guaranteed. Many partnered with their husband. Valerie Simpson and Nick Ashford, who arrived at Motown two years after Moy. Carole King and Gerry Goffin. Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry. Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann.

Therefore, after joining Motown, Moy was offered a fighting change—producer Henry “Hank” Cosby, who worked with the 11-year-old Little Stevie when he arrived at the label, offered to take her under his wing. Nevertheless, opportunities remained limited. Quiet and mild-mannered, Moy was the only woman in the all-male producers’ meetings where songwriting assignments were handed out by Stevenson.

In 1965, during one meeting when none of her male colleagues volunteered to work with an almost forgotten artist, Stevie Wonder, Moy recalled Stevenson saying that Wonder would be let go. Unsettled with what she heard, as soon as the meeting adjourned, Moy approached her boss to tell him how she didn’t believe it was over for him. Begging Stevenson for the opportunity to work with the now-15-year-old, she negotiated that if she could write and produce a hit for him, Wonder could remain at Motown.

After the song was completed and released, Moy kept her end of the bargain, writing a No. 1 R&B song for Wonder called “Uptight (Everything’s Alright).” The catchy dance tune, which also topped the pop charts, earned him his first two Grammy Award nominations, Best R&B Song and Best R&B Performance, solidifying him not only as an instrumentalist but as a well-developed singer with a mature sound that Gordy now praised.

In terms of formally receiving the label credit she deserved as a producer, however, Moy was denied. While Moy and Raynoma Gordy Singleton both asserted Moy's role as a producer, only Stevenson and Cosby were credited. In fact, in Stevenson’s 2015 memoir, The A&R Man, he said, “Just between you and me, I would have loved to have had a female producer who could make hit records. Can you imagine the publicity we could’ve gotten out of that?” It’s no wonder that official paperwork never reflected Moy’s contribution at Motown or in music history as a pioneering producer, making the depth of her labor ignored and invisible.

Today, some still find it hard to believe that during Wonder’s early career he didn’t write his own lyrics. While it was customary during the Sixties to place the spotlight on the stars at Motown, rarely were those behind the scenes ever mentioned.

Yet, Moy was a central yet overlooked architect of the Motown sound, breaking down gender and racial barriers while opening doors to pave the way for all women across the music industry.

This is the same woman who would go on to write more classics with the teen Wonder, including “I Was Made to Love Her,” and “My Cherie Amour.” Even with the odds stacked against her, Moy attained industry recognition as a solo songwriter. At Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI)’s first-ever R&B ceremony in 1969, Motown cleaned up in a three-way tie against Norman Whitfield and duo Ashford and Simpson. Moy won the 1968 BMI Rhythm and Blues Songwriter of the Year Award for Wonder’s “I Was Made to Love Her” and “Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Da-Day” along with Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’ “Honey Chile.”

Other noteworthy classics by Moy include Kim Weston and Marvin Gaye’s “It Takes Two,” The Isley Brothers’ “This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak For You)” along with Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’ “My Baby Loves Me” and “Honey Chile.” And early on because Motown had limited resources but tons of ingenuity, all hands often would be on deck in the recording studio to do whatever was needed.

Listen closely to The Supremes’ 1964 song “Baby Love.” Though uncredited, at least one pair of the heels stomping on boards in the background throughout belonged to none other than Sylvia Moy.