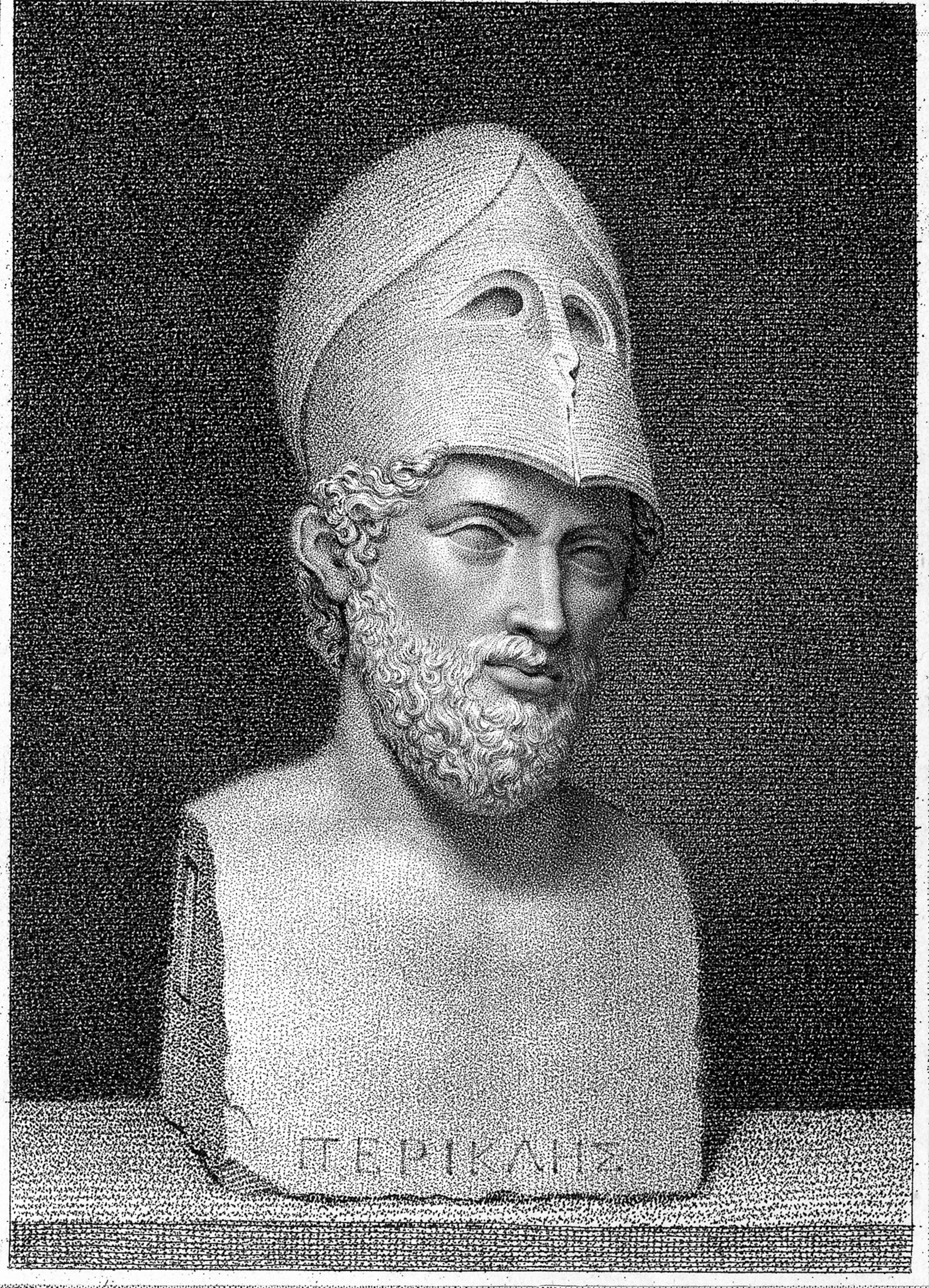

The ancient Greek statesman Pericles (ca 495–429 B.C.) left his mark on the world in far more ways than the iconic Acropolis that still defines the skyline of Athens. He advanced the foundations of democracy and governed during Athens’s Golden Age, when the arts, architecture, and philosophy—as well as Athens itself—reached new heights.

Pericles first made a name for himself in the city-state during his 20s as a wealthy aristocratic arts patron. At the Dionysia Festival in 472 B.C. he sponsored the play Persians by the great tragic playwright Aeschylus.

Politics soon took priority over the arts for Pericles. In 461 B.C., he joined the reformer Ephialtes in organizing a vote in the popular assembly that stripped all remaining powers from the Areopagus, the old noble council. Many historians consider that event to have marked the birth of Athenian democracy. After Ephialtes was assassinated in 461 B.C., Pericles emerged as Athens’s foremost politician, and he would lead the popular assembly and the city until his death three decades later.

Pericles ushered in what is considered “radical democracy.” This meant that ordinary Athenian citizens were paid by the state to participate in public affairs. Previously, only the wealthy could afford the time to participate in politics. Pericles approved payment for jury duty and for soldiers, sailors, and administrators. That development transformed the character of Athenian democracy and society; lower-class Athenians (called thetes) could now participate as fully as citizens with property. A noted orator, Pericles stated in his famous Funeral Oration that Athenian citizens regard “a man who takes no interest in public affairs not as a harmless, but a useless character.”

Athens at war and peace

Pericles also elevated Athens’s role within the Delian League, a naval alliance of Greek city-states unified to fight the Persians. He maneuvered Athens to primacy over other league members, first by transferring the league’s treasury to Athens in 454 B.C. and then by imposing Athenian weights and measures on all league members three years later. The Delian League effectively became an Athenian empire.

Around 449 B.C., the Delian League signed the Peace of Callias, which ended nearly 50 years of fighting with the Persians and ushered in two decades of peace. To honor the gods for the victory and to glorify Athens, Pericles proposed using the Delian League’s treasury to mount an unprecedented building campaign.

Work began in 447 B.C. to turn the rocky hill known as the Acropolis into a breathtaking temple complex. More than 20,000 tons of marble were used, producing the iconic Parthenon and the imposing colonnade of the Propylaea, the entrance gateway. The arts and philosophy also flourished during Pericles’ reign, when Socrates and the playwrights Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes produced some of their finest works.

But the peace of Athens was not to last. In 431 B.C., Pericles urged the popular assembly to declare war against Sparta. “It is from the greatest dangers that the greatest glories are to be won,” he stated in front of the assembly. Unfortunately, the 27-year-long Peloponnesian War resulted in great losses for Athens. When a plague broke out, an estimated 20,000 people died—including Pericles and his two legitimate sons. Athens lost its “first citizen,” but his legacy endures in the Athens skyline and in democratic institutions around the world.

Athens: power and glory

Athens was one of the most important and powerful cities in the ancient world. The bustling main thoroughfare was the Panathenaic Way. For the annual summer birthday celebration of Athena (the Greek goddess of wisdom for whom the city is named), a procession started at the Dipylon Gate—the largest of 15 gates in the city—and marched more than a mile to the Altar of Athena on the Acropolis. Men gathered frequently at three public gymnasia to prepare for the (naked) athletic competitions in the Panathenaic Stadium.

The thousands of citizens who participated in Athens’s fledgling democracy attended the popular assembly at the Pnyx, a rise in the center of the city. But the heart of daily life was the agora, or marketplace, a sprawling complex of more than 200,000 square feet that featured trade in everyday items but also sported brothels, bars, and bathhouses.

Herodotus, the historian

The ancient Greek Herodotus is considered by many to be “the father of history.” It is from his groundbreaking work, the History, that our modern meaning of the word was handed down through time. Bequeathed, too, was his innovative approach of conducting an orderly, thorough examination of the past to explain the causes—and outcomes—of past events. He traveled the far reaches of the Persian Empire, recording his own personal inquiries (which he called “autopsies”), as well as the multitude of myths and local legends he heard along the way.

While the theme of the History was the Greco-Persian Wars, Herodotus’s purpose was far broader and enduring: “in order that the deeds of men not be erased by time, and that the great and miraculous works ... not go unrecorded.”