What Maui’s tattoos in ‘Moana’ say about Polynesia’s tattoo culture

Tattoos in places like Samoa, Tonga, and Hawai‘i can signify a sacred oath to protect and honor one’s community.

Audiences are buzzing with anticipation for another rich adventure through Polynesia in Moana 2. The first film was celebrated for its joyous honoring of Oceanic cultures, nominated for two Oscars, and made more than half a billion dollars worldwide. Who knows how far this one will go?

Experts across the Pacific, including the islands of Fiji, Tahiti, and Samoa helped bring to life the demigod Maui—a shapeshifting trickster with humor and heart, plus a set of impressive pipes. His character has deep roots in Polynesian myth and folklore.

(Get tickets for Disney's Moana 2, now playing in theatres everywhere.)

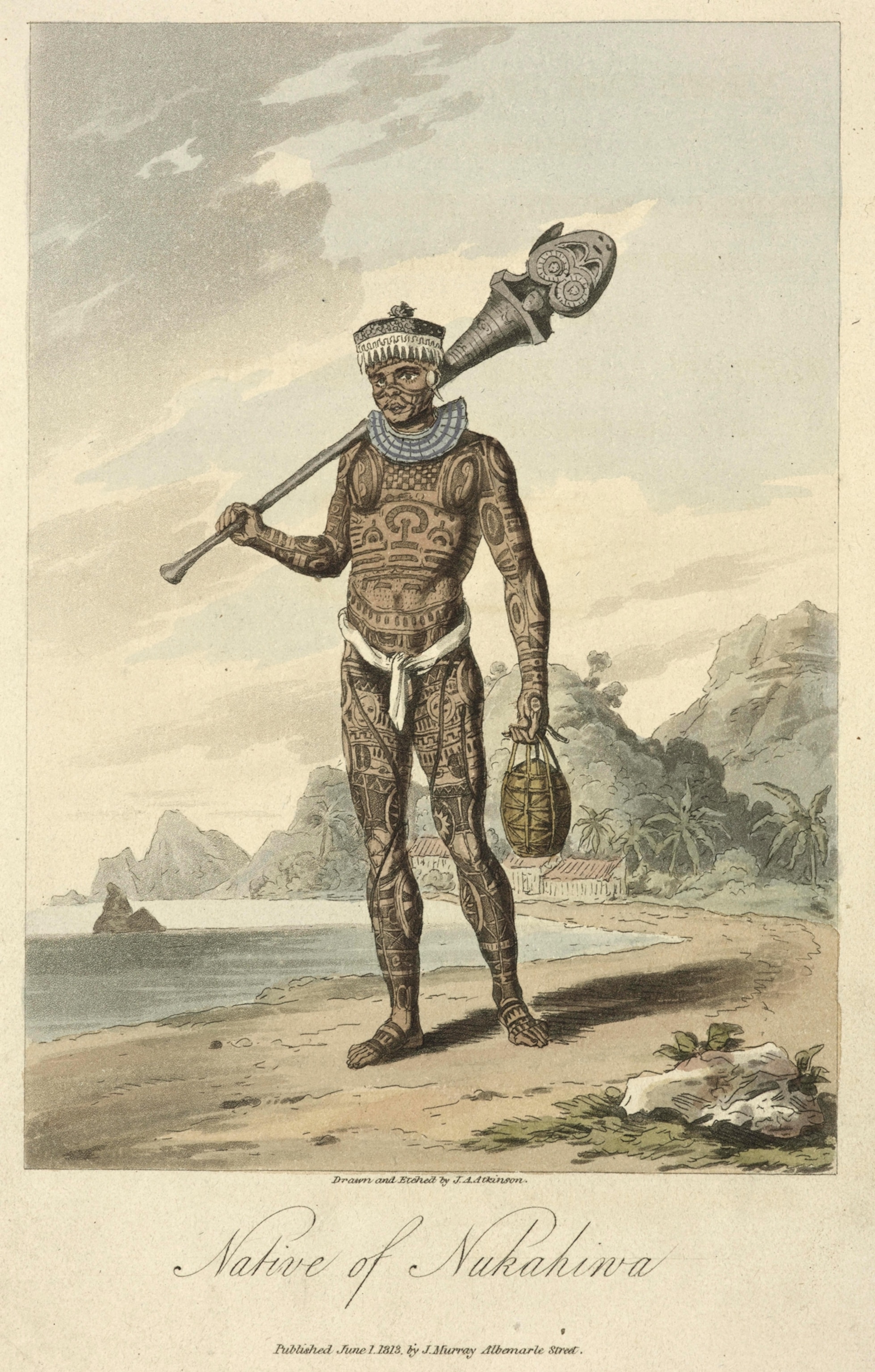

From his signature tattoos, we can learn about the place of the practice across the Pacific Islands, what its images communicate, and how tattoos tie leaders to their communities.

Who is Maui?

Although stories surrounding his character vary, Maui has a place in legends across the islands as a demigod. Tales of his exploits, including pulling up the islands, are one common thread. “Each island tells a slightly different story,” says Su‘a Sulu‘ape Toetu‘u, a Tongan tattooist based in O‘ahu.

One of Maui’s most famous legends is his slowing of the sun, a feat he accomplishes by snaring it with a magical rope, allowing longer days for the people to work. Maui references this story in Moana when he sings “You’re Welcome.” “In Tongan culture, Maui fixes everybody’s mishaps or problems,” Toetu‘u says. “For us, Maui was a working-class hero who was for the people.”

In Māori legend, Maui and his brother fished in a canoe that is now the South Island of New Zealand (Te Waipounamu). Using a fishhook taken from his grandmother’s jawbone, Maui captures the giant fish now known as the North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui). Over in Hawai‘i, it’s said that Maui went fishing with his brothers and pulled up the Hawaiian islands with his magical fishhook. “We may be from Tonga, Samoa, Hawai‘i or Tahiti, but we’re all one people,” says Toetu‘u. “We tell his stories to our children over and over again. He’s a real person to us.”

Maui’s tattoos

In 2011, Disney filmmakers John Musker and Ron Clements embarked on a research trip through Polynesia for Moana. This expedition led to the creation of the Oceanic Trust, an eclectic group of historians, anthropologists, linguists, and cultural practitioners who shaped many of the film’s details. Among them was master tattoo artist Su‘a Peter Sulu‘ape and anthropologist Dionne Fonoti. They were key in getting the movie’s tatau (Samoan for tattoo) designs just right.

Su‘a belongs to a long lineage of Samoan tattoo practitioners—one of two remaining practicing families, he says. “It’s jealously protected knowledge,” says Fonoti. Certain elements of tatau are sacred, so much so that only few carry the knowledge.

They wanted to “make sure that these characters have characteristics that Samoans would recognize,” says Fonoti. “We know what tattoos look like today, so what might it have looked like thousands of years ago?”

Maui’s tattoos were purposefully designed as narrative exposition rather than a realistic or accurate depiction of tatau. For example, an inked version of Maui lassos the sun on his chest. In Samoan culture, one’s achievements are not so explicitly tattooed. “Samoans have a great deal of humility. We never brag or praise ourselves in a literal sense. Even our language and how we express emotions, it’s very metaphorical,” says Fonoti.

Toetu‘u, who apprenticed under Su‘a’s father Su‘a Alaiva‘a, points out that “Maui bears ‘Neo-Polynesian Tribal’ tattoos, which is a contemporary style that began in the late 1990s as a fusion of Polynesian and Asian art, graffiti and illustration, mixed with tribal designs.” It is also understood throughout Polynesia that people of all ethnicities may bear Neo-Polynesian Tribal tattoos.

On the other hand, traditional tatatau (Tongan for tattoo) using handmade tools is reserved only for people of a certain ethnicity, descent and rank. “Tatatau is spiritual and sacred because it is anchored deeply in the people of Oceania’s heritage,” Toetu‘u says. “Some symbols reconnect us to our ancestors and to elements such as fonua (land), moana (ocean), langi (sky) and celestial stars for guidance as they navigate the vast ocean.”

When Toetu‘u practices tatatau, he will enter a different room sanctioned for this type of work. During the tattoo process, the door will remain closed. “There is weight to it. It’s an oath that you make to lay down and make that commitment to your people,” he says.

The individual receiving tatatau is joined by their family or village during the tattooing process so they can support him as he endures the mental and physical pain. These sessions may take weeks or months, and when the tatatau is complete, there is an ordination ceremony followed by a celebratory feast held by his family and village. “This ordination symbolizes his commitment and duty to serve his God, ancestors, family, and the village,” says Toetu‘u.

In the film, Maui also has a small, tattooed version of himself that comes to life on his body and has an attitude and mind of its own. Mini Maui takes on almost a Jiminy Cricket role, a conscience guiding Maui to make right decisions.

Traditional Hawaiian tattooist Kalehua Krug says that conscience applies to real-life tattoos too: “The marks left on your body are there to remind you of the commitment that you’ve made and should help guide your behaviors and decisions in the role that you’ve accepted in your community.”

In Hawai‘i, maka uhi (face tattoo) is another symbol of power and status. Krug bears multiple maka uhi—triangles run from the back of his head to his chin, and a thick black stripe across his mouth to represent his role as a ceremonial speaker.

“The idea of kākau (Hawaiian for tattoo) and putting designs on skin permanently reflects the concept of commitment in Polynesia,” he shares. “When you take on these designs, it is a physical manifestation of an agreement you’ve made with yourself, your ancestors and community. It is a sign of kuleana (responsibility).”

Markings of leaders

Moana’s father and chief Tui bears the pe‘a, an intricate body tattoo traditionally worn by Samoan chiefs. The pe‘a have distinctive black bands, arrows and dots, spanning from the middle of the back and down to the knees, representing the bearer’s readiness to serve their community and lead with honor. Each linear row differentiates families, ranks and profession.

“It was important to take into account Tui’s rank in Motunui, as well as his personality and how he speaks to his people… the pe’a represents what kind of person he is,” says Su‘a. “His pe‘a signifies service, kuleana to the ocean and the land.”

The pe‘a stood out immediately to Su‘a Sulu‘ape Pili Mo‘o, a fellow tattooist based on Maui. “I was very happy to see that Disney got that right by giving Moana’s father this tattoo reserved for chiefs,” he says. Like Hawai‘i’s maka uhi, the process of receiving a pe‘a is grueling. Taking weeks or even months to complete, it’s considered a rite of passage for those ascending to leadership roles. Refusing or failing to complete the tattoo process is seen as a sign of weakness, unfit for a person in power.

Certain chief designs are sacred motifs designated for certain parts of the body, symbolizing ancestral lineage. “These tattoos identify rank and leadership as an oath to serve their territories,” Toetu‘u explains.

In Moana 2, Su‘a has left his mark once again, this time unveiling new tattoo designs on Matangi, a debut antagonist. He and Fonoti also assisted Disney in creating the Samoan motifs you might see in the film’s petroglyphs, clothing, and canoes.

“It has been a big responsibility,” says Su‘a. “Tattoos are a very important part of our culture. From day one, I’ve wanted to make sure I was able to keep our culture on the right side of the road, that we are actually telling the right and true story. I hope that I was able to bring our culture to light for viewers.”