An unlikely band of water defenders fights chronic shortages in El Salvador

They battle sexism and bureaucracy to bring water to those most affected: women in their communities. “We women were those most in front of the fight.”

Santo Tomás, El Salvador — For months, Jenny Marilyn Sánchez was stuck inside her home, perched at the top of a hill in an urban neighborhood of Santo Tomás, a municipality about 20 minutes south of the capital city of San Salvador.

The country’s president had been encouraging citizens in press conferences and speeches to stay inside and wash their hands during the pandemic. Sánchez wanted to follow this advice but the faucets in her kitchen and bathroom were running dry, a common occurrence for about half of the Salvadorans who have indoor plumbing.

The last time she had running water, Sánchez made sure to fill her plastic buckets, a ritual all too familiar to many Salvadoran women. “The women are the people who worry the most about water because we have to bathe the kids and wash the dishes,” she says.

For weeks during the height of the pandemic, Sánchez’s only way to bathe was by pouring cold water from the buckets over her head. She did so sparingly to have enough water left to cook, clean, and wash clothes for herself and her teenage son.

The amount of time without water was “outrageous,” she says. But she didn’t just sit back and wait for help. She picked up the phone and began calling the local government water agency. When that didn’t work, she posted on their Facebook page, hoping the public call-out would push them to act.

In recent years, Sánchez and other women from Santo Tomás, which is home to 25,000 people, have become an unlikely band of water defenders, organizing in formal and informal ways. These women, mostly mothers in their 40s and 50s, aren’t afraid of confronting officials, waiving picket signs, or coordinating phone and social media campaigns. Sánchez, 44, is not part of any organized movement, but often works with her neighbors to demand water access when they face shortages.

With long skirts and traditional lace and floral bandanas tying back their gray-streaked hair, they don’t look like the younger feminist activists that often march through the streets of Latin America with green bandanas in support of abortion access and messages scrawled across their bare chests. But their demands are just as important.

Women are often disproportionately affected by water scarcity, according to UN Water. They’re in charge of managing their households, which includes making sure there’s enough water to cook and clean, and they need it for female hygiene. That’s why women are more likely than men to be on the front lines in the struggle to bring water to their communities.

The pandemic has laid bare the scope and impact of the water crisis in El Salvador, where an estimated 90 percent of water is unsuitable for drinking, according to a government study. About 15 percent of Salvadorans don’t have running water in their homes and have to collect water from communal pipes and wells or from the nearest river, according to a 2020 study by the University of Central America. (Discover how weak regulations, lagging services, and climate variability are fueling the country's water crisis.)

Sánchez is one of the lucky ones in Santo Tomás. Her home has a drainage system. She gets running water through a system of pipes built by the public water agency, known as ANDA, that pulls water from a nearby river—when there aren’t shortages that leave her tap dry.

Women in the rural communities of the municipality, which stretches for about nine square miles, have to make their way through dirt roads and fields to reach public faucets sprouting from the ground. There, they fill plastic water jugs and buckets to carry back to their homes.

Access to water and proper hygiene could reduce COVID-19 deaths worldwide by more than 6 percent, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but the women of Santo Tomás aren’t able to take all the recommended precautions, including staying at home.

“If we confine the women who are responsible for stocking their houses with water, it is taking away the rights that they have and it is violating their access to health,” says Isabel Quintanilla, an anthropologist and expert in feminist environmental organizing through REDIA El Salvador, a coalition of researchers on environmental issues.

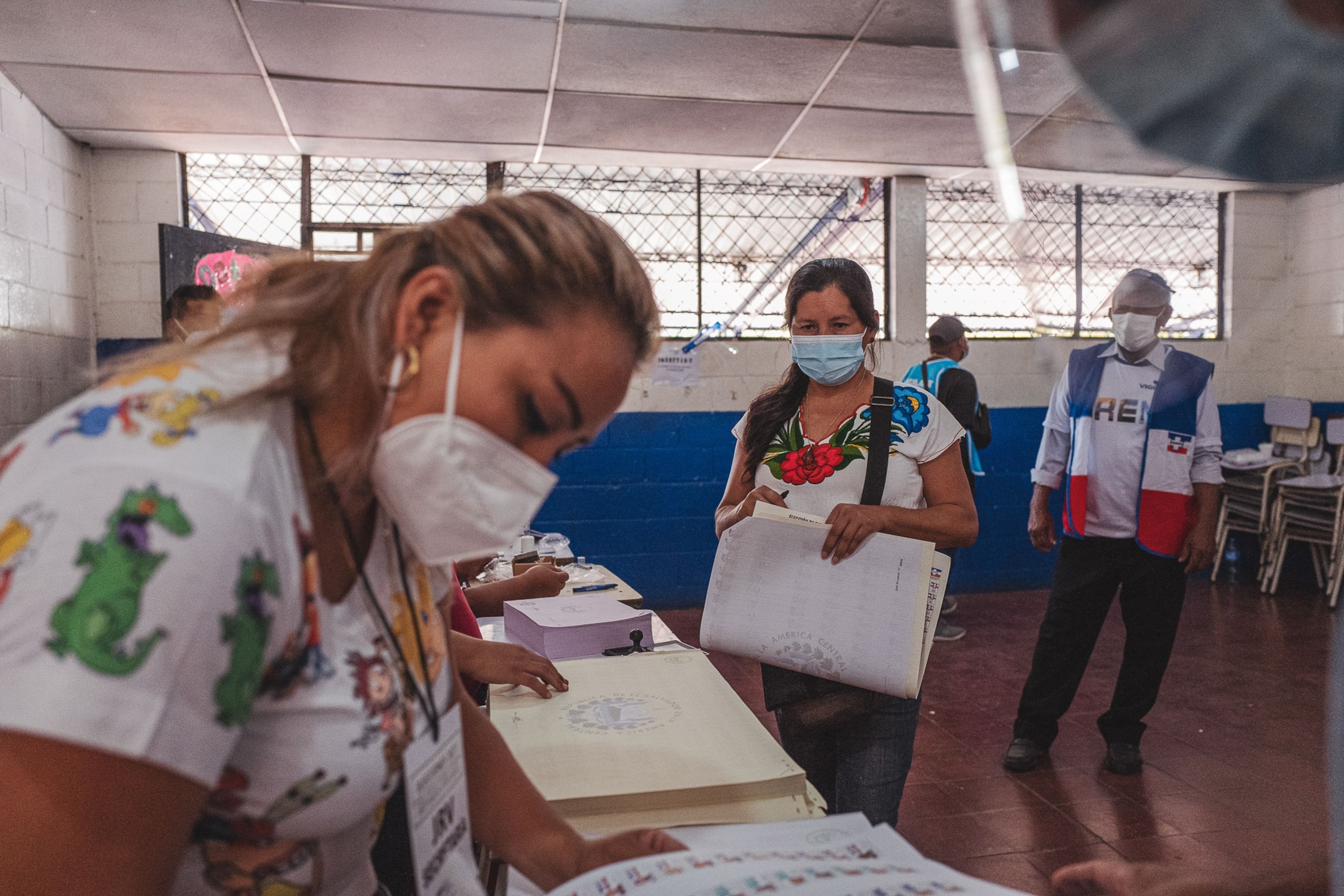

As of mid-March, El Salvador’s Health Ministry had reported more than 60,000 cases nation-wide and 340 cases in Santo Tomás, although a lack of testing in the area may result in an undercount. Strict stay-at-home orders have been relaxed, but the country maintains a public health alert. El Salvador began vaccinating citizens in February and has since vaccinated more than 41,000 people, about 6 percent of the population.

“We can’t talk about health measures to fight COVID if we don’t have water,” says Sonia Sánchez, Jenny’s sister and the leader of the Women’s Movement of Santo Tomás (MOMUJEST), an organization founded in 2009 to support local women in their most pressing daily challenges, including food insecurity, economic independence, and access to water. Membership is now at about 75 women from different neighborhoods.

Sonia is no newcomer to the struggle for water. Since 2015, she has been part of a group of women trying to fend off a major development project that would increase the demand for water, leaving less to go around in Santo Tomás.

She and other environmentalists argued that construction of a new apartment complex should not be allowed because of its damage to the environment. They began protesting the project, showing up with signs outside the construction site and reporting the company for its lack of proper permits.

As tensions between the community and developers heated up, Sonia Sánchez remembers that the men opposing the project slowly stopped showing up to meetings and protests.

“We women were those most in front of the fight,” she said. “We met behind closed doors and analyzed what had happened and asked, ‘What do we do?’”

Activism has traditionally been male-dominated in El Salvador, but in recent years women have become more involved, particularly in terms of environmental rights, according to Quintanilla. They often end up facing sexism from the people and institutions they oppose as well as from their own husbands and fathers.

“These situations can discourage many female activists to join in a more meaningful way and take a more leading role,” Quintanilla says. “Luckily in this case of Santo Tomás, the women haven’t paid attention to these forms of resistance that come up.”

After a years-long battle, the apartment complex was built anyway when the Ministry of Environment granted the required permits. The company accused Sonia of defamation and slander. But in a 2016 trial, Sonia was acquitted of the charges.

The pristine white complex, with its lush green grass requiring constant irrigation, stands as a stark reminder of the unequal access to water in Santo Tomás and El Salvador.

Even though these women couldn’t stop the construction of this development, their activism prepared them for battle during the pandemic.

In Caña Brava, a rural Santo Tomás community of mainly subsistence farmers living in houses with tin roofs, dirt floors, and no indoor plumbing, residents draw water from a few public faucets, slim pipes jutting out from the community’s dirt roads.

They say the water pipes have burst about twice a month during the pandemic, leaving them without water for up to a week at a time.

María Lilian Sánchez (no relation to Jenny or Sonia Sánchez), a 57-year-old seamstress, was left without water recently when she forgot to fill her plastic water bins and pila, a traditional water receptacle made of stone or ceramics.

She didn’t have enough money to buy water, either: Her husband had lost his job and her sewing work dried up during the pandemic. “A friend sent me about 25 small bags of water,” she says, referring to serving-size packets sold at many grocery stores. “Because I had absolutely no water.”

When the water authorities didn’t come to fix the pipes, residents said they had to make repairs themselves.

Then yellow construction trucks arrived unannounced to build a new well in Caña Brava. The women worried authorities planned to divert the community’s already scarce water to another neighborhood.

Years ago, they might have watched the construction without complaining. But since they started learning more about their rights through MOMUJEST, they recognized the power of their voices.

“We all went to ask, ‘For whose benefit were they making this well?’” says Norma Esperanza Martínez, 40, a member of the local community council.

After the women expressed their concerns, authorities agreed to expand the project so it would benefit local residents too. They said they will build indoor plumbing for dozens of houses in Caña Brava, according to Martinez. (Local authorities from Santo Tomás and the national water agency did not respond to a request for comment.)

Residents are pleased with the tradeoff because they say it will help women save time from having to fetch water or wash clothes in a nearby river. “It affects us a lot as women because water is used daily and in every moment,” says Martinez.

Meanwhile, about a mile and a half away, Jenny Marilyn Sánchez and her neighbors also celebrated a win. Their water service was finally restored after nine weeks.

Both cases had one thing in common, says Sonia Sánchez. “It was the women who were present in the process.”