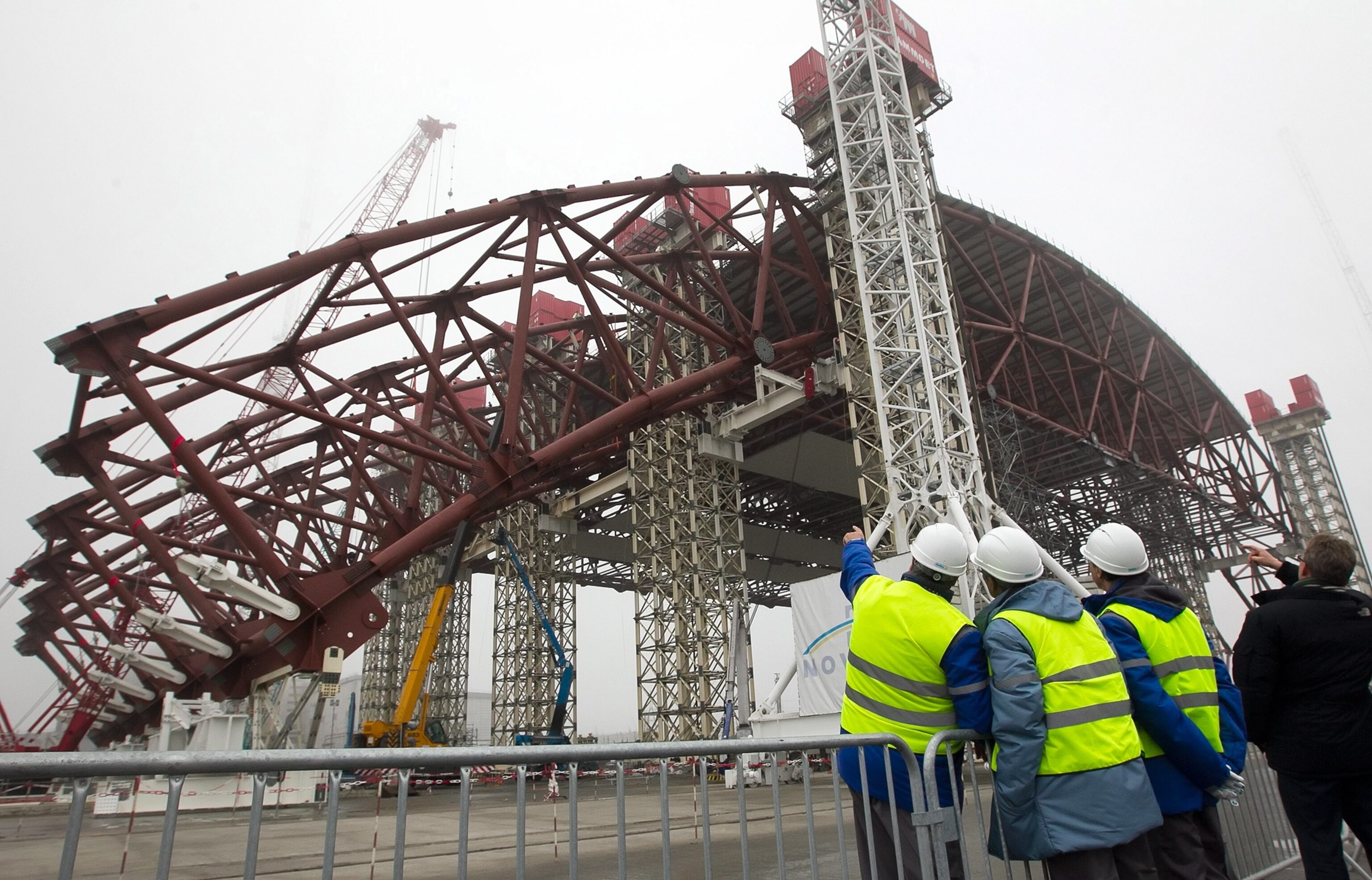

Visitors gaze overhead at the steel lattice that will underpin the new protective shelter at Chernobyl, site of the worst nuclear accident in history. The so-called New Safe Confinement, designed to seal the destroyed reactor and contain the radioactive material inside, is the latest step in a more than 26-year cleanup at the desolate plant site in Ukraine. (Related Quiz: "What Do You Know About Nuclear Power?")

On April 26, 1986, an explosion in one of the plant's reactors spewed large amounts of radioactive material over Ukraine, Belarus, and western Russia. The immediate area was evacuated, but the cloud that rose from the burning reactor spread iodine and radionuclides over much of Europe. Some 30 workers were killed immediately, and as many as 4,000 people are expected to die eventually as a result of radiation exposure from the Chernobyl plant, by the World Health Organization's reckoning. Some estimates of the excess cancer toll are far higher. Immediately following the accident, workers braved dangerous conditions to build a steel and concrete structure to contain the uranium, plutonium, and other radioactive materials at the ruined plant. Known as the "sarcophagus," the structure was never meant to be a permanent solution. It is supported by faulty beams and has developed cracks, causing experts to worry it could collapse and once again allow radioactive material to escape.

A plan for a more permanent protective solution, developed more than 15 years ago by European and Western experts, finally is being put into action. The $2 billion (1.6 billion Euro) effort, funded by more than two dozen nations and the European Union, is "an unparalleled project in the history of engineering," says the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the project administrator.

After shoring up the sarcophagus, workers raised the first section of the new structure’s arched roof, seen here in November. The new shelter will eventually cover the damaged reactor. The mammoth structure, which is slated for completion in 2015, will weigh 29,000 tons and stand tall enough to house the Statue of Liberty.

—Joe Eaton

Pictures: Race Against Time to Build a New Tomb for Chernobyl

In an unprecedented engineering endeavor, workers are replacing the crumbling structure hastily erected to contain radiation at Chernobyl, site of the world's worst nuclear power disaster in 1986.