Scientists record coldest ocean temperature ever in Earth's history—and wonder how life survived

Ancient rocks once beneath the ocean hold clues of severe conditions unimaginable on today's planet.

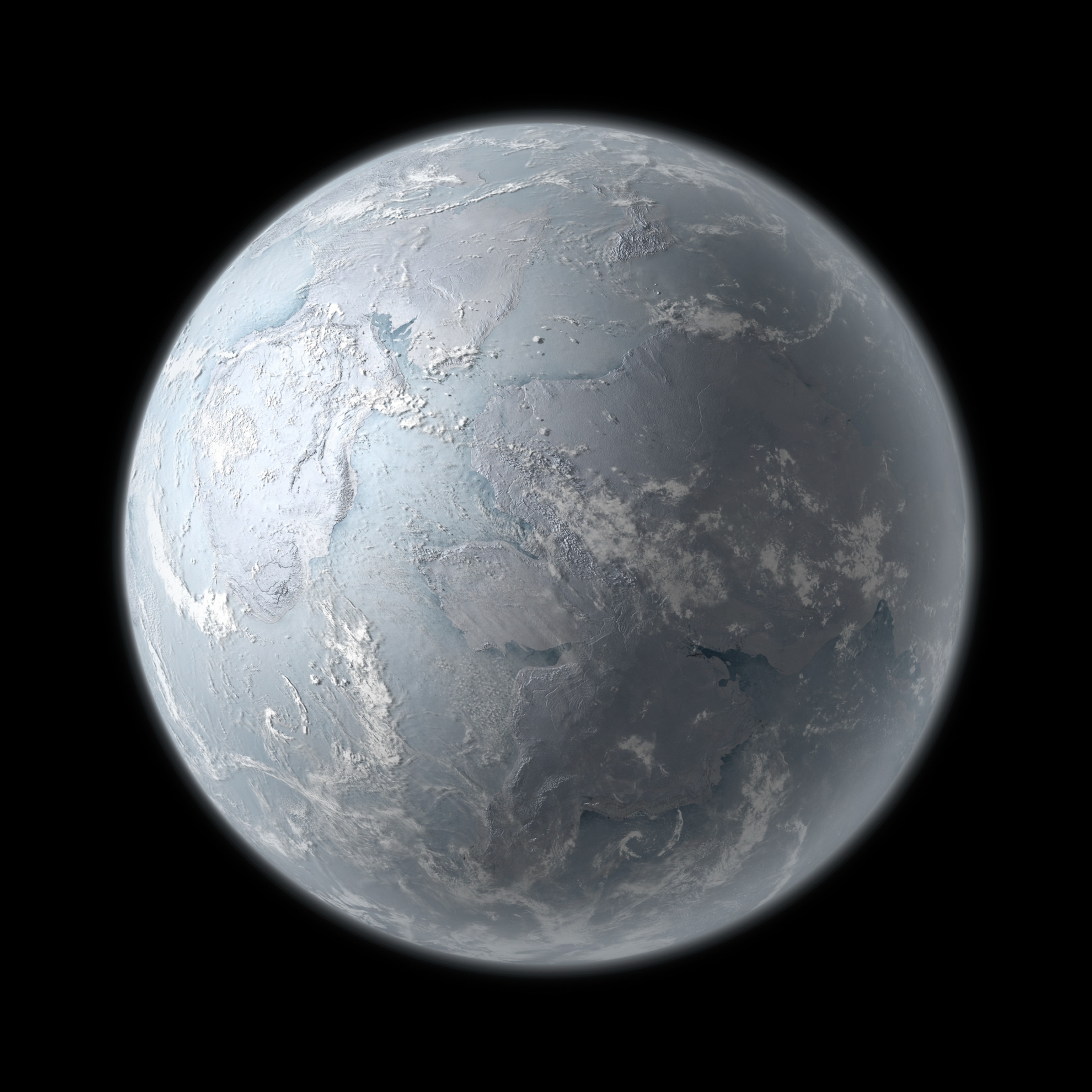

About 700 million years ago, Earth was entombed in a veneer of ice hundreds of feet thick—a frozen state scientists refer to as “Snowball Earth.” Oceans cooled but managed to retain some heat to avoid freezing.

Now, researchers have an estimate—published in Nature Communications—of how cold and salty oceans were during this period.

By analyzing data from rock deposits, the study’s authors estimate that sea temperatures were 5°F (minus 15°C). That’s about 22°F (12°C) cooler than even the coldest ocean temperatures today. The study also notes salinity was more than four times higher, allowing the ocean to get extremely cold without freezing. These estimates suggest all the microbes, phytoplankton, algae, and sponges that lived on Earth during this time endured even harsher conditions than scientists suspected.

“These new temperature and salinity numbers raise the bar on environmental stress,” says the study’s coauthor, geologist Ross Mitchell of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

An anomaly in ancient rocks

The team’s research was sparked when another study coauthor, geologist Paul Hoffman of the University of Victoria in British Columbia, wondered whether the temperature of Snowball Earth’s ocean could explain an anomaly in data previously collected from layers of iron deposited on rocks on the sea floor.

These bands of rust formed because oceans suddenly received pulses of oxygen that reacted with dissolved iron that had accumulated in the water.

According to research led by another of the study’s coauthors, geologist Maxwell Lechte of the University of Melbourne, the iron deposits were located near ancient coastlines where glaciers met the seas and oxygen-rich meltwater under the ice seeped into the ocean.

But the deposits during Snowball Earth had much heavier iron particles than layers of iron that were deposited on ocean rocks about 2.4 billion years ago; Hoffman wondered if the temperature's that existed in the Snowball ocean caused these iron deposits.

Mitchell then worked with the study’s lead authors, geochemists Kai Lu and Lianjun Feng, also of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who calculated the ocean temperature that could explain the excess of heavier rust particles—a frigid 5°F.

“I like the approach they used,” says geochemist Timothy Conway of the University of South Florida, who was not involved in the study. “It’s based on experimental data and a theoretical model where they’ve made assumptions, but it seems to make sense.”

The team also considered the possibility that the anomaly was caused by heavier iron particles present in the Snowball ocean from glacial erosion on land or hydrothermal vents, but their analysis showed this wasn’t likely.

They also calculated that the oceans adjacent to the ice margins must have been more than four times saltier to lower the freezing point of the water enough to prevent it from freezing over.

How did life survive?

Scientists have been studying how life could have survived the Cryogenian era, which includes the Snowball Earth period, plus another such episode about 650 million years ago.

One theory is that life was more adapted to the extreme conditions of limited oxygen and little to no light, or that life persisted at hydrothermal vents where it could produce food from other chemicals.

Another theory is that life survived in meltwater ponds on the ice, like the cyanobacteria and algae that currently live on the McMurdo Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

“These surface settings could have enabled a diverse assemblage of life to persist and continue to evolve throughout the glaciations,” says geochemist Fatima Husain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the study but led research on this topic last year.

Yet another possibility is that organisms survived or moved to ice margins to access the oxygen in the meltwater at the base of ice. But they would have had to deal with the extreme conditions predicted by the new study. Lending weight to this possibility is bacteria that have been found living in similarly cold, salty brines underneath the ice on Lake Vida, Antarctica.

“We keep learning more about how extreme the Cryogenian was,” says Husain, “ and that makes life persisting and diversifying dramatically after that, all the more amazing.”