What drew these 1,300 perfect circles on the sea floor? We may finally know.

When hundreds of eerily perfect circles were discovered on the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, theories abounded about what they could mean. Four years of underwater research revealed a lost world.

On a bright, hot day in mid-September 2011, Marine biologist named Christine Pergent-Martini was hunkered down inside the cabin of a small research vessel, a 97-foot-long catamaran, cruising through the Mediterranean Sea about 12 miles off the coast of Corsica. Outside the ship’s windows, the sun glinted off the dark-blue water, but Pergent-Martini ignored the waves. She was more interested in what lay beneath them.

A monitor in front of her displayed images from the vessel’s onboard sonar system, which was emitting a series of short acoustic pulses to reveal the underwater topography about 400 feet below. The ocean scientist was nearing the last day of a month-long mission: With a small crew, including her husband, oceanographer Gérard Pergent, and a graduate student from the University of Corsica Pasquale Paoli, Pergent-Martini had been mapping the seafloor in this region. The seemingly simple goal actually targeted one of oceanography’s major blind spots.

The Mediterranean Sea covers about a million square miles, stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar in the west to Lebanon in the east. While its surface has been traversed since ancient times by everything from Greek triremes to Etruscan warships, its depths are mysterious to modern science. Much of its seafloor exists in something of a liminal zone: too shallow and close to the shore to draw interest from deep-sea mining companies but still too deep to be reachable by conventional scuba divers. Pergent-Martini and her colleagues wanted to learn more about what lived on the bottom at these depths. At first, the day was no different from any other. As the boat moved across the water, the scientists watched a series of predictable grainy black-and-white images appear on-screen: Sand. Small rocks. More sand. It was all stuff they’d seen before. But then something truly bizarre scrolled into view.

A perfect circle, then another, then another. They were all about the same size—around 67 feet in diameter—with a distinct outline and striking symmetry. Weirder still, almost every ring had a dark spot directly in the center. They looked like fried eggs, Pergent-Martini thought, and there appeared to be several dozen of them.

The scientists looked at each other. “We had no idea what it was,” Pergent-Martini says. Her team carefully logged their location and used a remotely operated vehicle to gather images.

Still, the mystery only deepened. They captured video footage of the circles, but the view was too murky to confirm much more than the fact that this wasn’t sunken cargo.

When the researchers presented their findings at a 2013 scientific meeting, they were still in search of answers about the nature of the rings. Even a follow-up study with a submarine in 2014 didn’t answer all their questions. In time, researchers would count more than 1,300 of these circles over a nearly six-square-mile area.

After years of applying for grants to study the rings more closely, the Pergents reached a dead end. “It was very difficult to obtain money,” Pergent-Martini said. The Pergents are specialists in seagrass meadows, and this was a bit outside their focus. “We had no way to go farther.” Then, just the right person got in touch.

In the world of undersea exploration, Laurent Ballesta is known for going to extremes. A photographer, marine biologist, technical diver, and National Geographic Explorer, he co-runs Andromède Océanologie, a company that leads scientific missions to document some of the world’s most inaccessible places. These undertakings often require specialized equipment and elaborate dive plans.

In Antarctica, for instance, he once used a bespoke system of cables to photograph the underside of an iceberg. In South Africa he has explored deep underwater caves to capture images of rare coelacanths, which were thought to be extinct for millions of years before small, fragile populations were rediscovered. And in French Polynesia he’s used a customized rebreather system to stay underwater for 24 hours at a time to observe the hunting habits of gray reef sharks, as chronicled in a 2018 story for National Geographic.

Ballesta and his team are always on the hunt for their next target. He also had a connection to the Pergents—he’d studied under them while working toward his master’s degree. So when he read his former teachers’ scientific paper about the mysterious pockmarked sonar scans, he was riveted. Some organisms have been known to grow in circular formations—corals make atolls, for example. But these rings repeated with an eerie regularity.

(Scientists discover world’s largest coral—so big it can be seen from space.)

“How is this possible?” he remembers thinking. Perhaps they were craters caused by erupting underwater vents or a strange geological formation. Pergent-Martini and her husband had a different hunch. Based on their submersible explorations, they believed the rings were coralline algae growing in a previously unknown shape. Another theory, put forth by some scientists, was that they were craters left by unused World War II bombs jettisoned by U.S. planes returning to their bases on Corsica. With the Pergents’ approval, Ballesta decided to pick up where they’d left off in hopes of solving the mystery, using their data to locate the rings.

In July 2020, Ballesta and two other divers from Andromède Océanologie arrived above the rings in their own research vessel and donned scuba gear to descend into the abyss. While they quickly sank to the bottom, they stayed there only about 30 minutes because they had to account for at least several hours of decompression time on the way back to the surface.

Equipped with a waterproof camera and lights, the team swam down through the bright upper waters of the ocean, the daylight gradually dimming to twilight. In less than two minutes they were approaching their destination, nearly 400 feet below the waves. “I stopped before I reached the bottom, some 20 or 30 meters up,” says Ballesta, “because I saw the rings.” They loomed out of the darkness, alien, enormous; they resembled gigantic platters etched onto the seafloor.

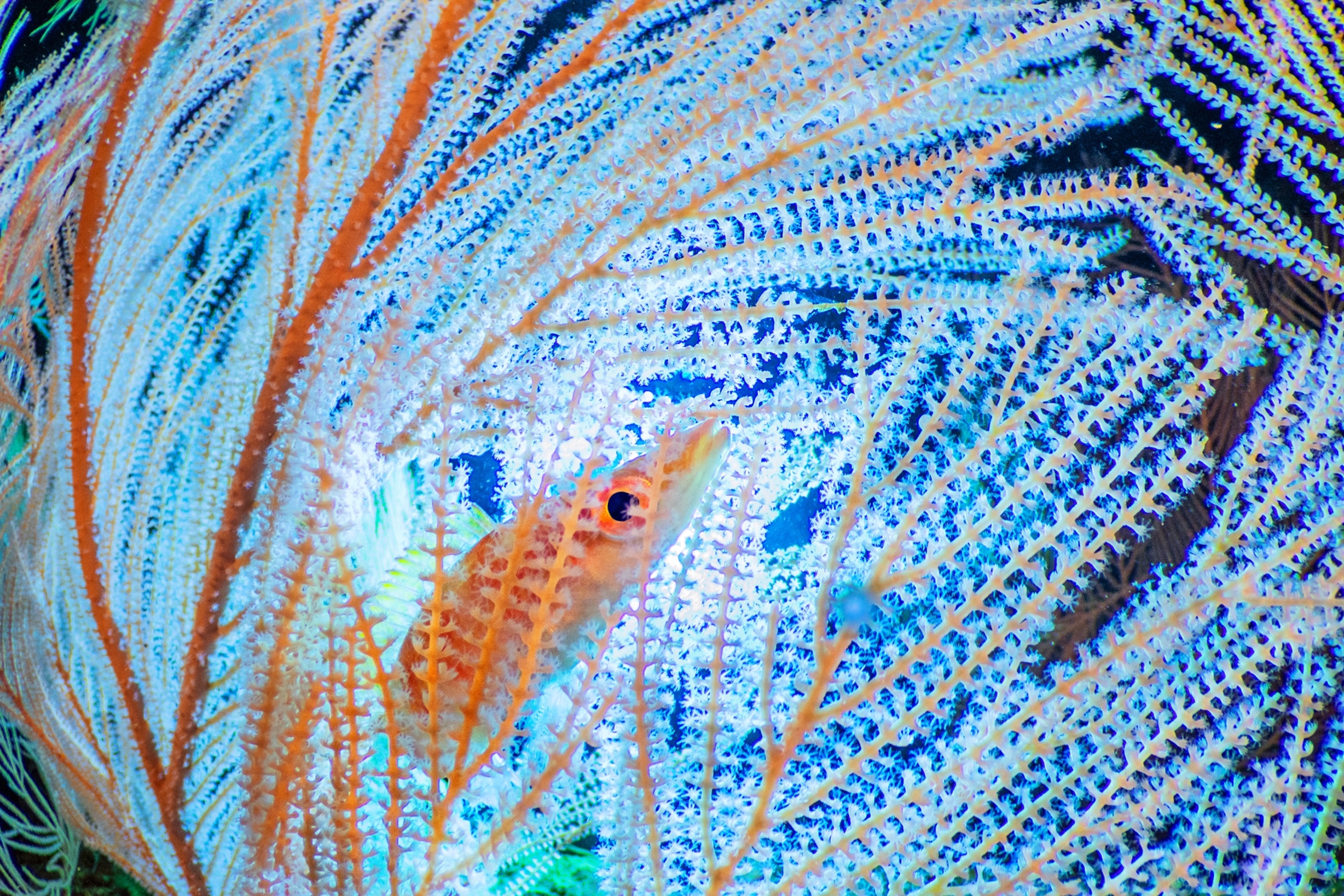

After he snapped some photos, Ballesta dived to the bottom and approached one ring. At its center was a large knob made by red calcareous algae, measuring around three feet high and several feet across, with swaying fanlike growths atop it. The knob was surrounded by a vast wasteland of pale, scree-like debris. And slightly downhill, about 30 feet beyond the center, was the dark outer ring, a circular perimeter that appeared to be made up of rhodoliths, a collection of craggy, firm, pebble-size algae. Looking at the structure, Ballesta realized that the Pergents were right. “It was alive,” he says.

(Sea creatures pollinate marine plants and algae, surprising scientists.)

After 27 minutes on the bottom, Ballesta and his crew spent nearly five hours gradually rising to decompress safely, allowing their bodies to equalize to the shifting pressure. Long before he got back to the boat, Ballesta was convinced he had to return. “I didn’t need 27 minutes,” he says about his time on the seafloor. “After the first minute, I knew.”

Julie Deter, a marine ecologist who was waiting for the team back on the ship deck, saw the excitement on their faces the moment they surfaced. Usually, by the time divers complete their long monotonous ascent, the thrill has faded. “But they were still very marked by what they had seen,” she says.

There was still no explanation for why the rhodoliths would have formed such perfect circles so many times over. Ballesta decided he needed to spend more time among the rings, which would require a way to stay longer in the depths.

In July 2021, Ballesta returned to the waters north of Corsica with three divers—Roberto Rinaldi, Thibault Rauby, and Antonin Guilbert—and a bold plan that would give them more time for exploration on the seafloor. They were inspired by divers on oil rigs who can quickly travel back and forth to the ocean bottom. At the surface, those rig divers live in sealed, pressurized chambers that match the conditions beneath the sea, where the pressure can increase by 10 or more times. They can then rapidly ascend and descend in a diving bell without having to slowly adjust to the change in pressure.

(How billions of dollars and cutting-edge tech are revolutionizing ocean exploration.)

Inside their own chamber at the surface, Ballesta and the others would live a bit like astronauts. Food would be passed in through an airlock. When they were ready to descend, they’d suit up and squeeze into the diving bell that would take them down to the seabed.

The team had expected to spend three weeks exploring the rings and nearby reefs, but the weather turned against them. Heavy wind and waves rocked the boat, making leaving the chamber dangerous on several occasions. For multiple days, the four men were trapped, unable to see out of their increasingly humid chamber, which barely held their small beds and a dining table. Ballesta’s voice turns bitter as he recalls this period. Time for exploration was precious, and they were spending it reading novels.

Finally the weather shifted, offering them the chance to drop down through the elevator chamber. “We found ourselves in another universe,” says Guilbert.

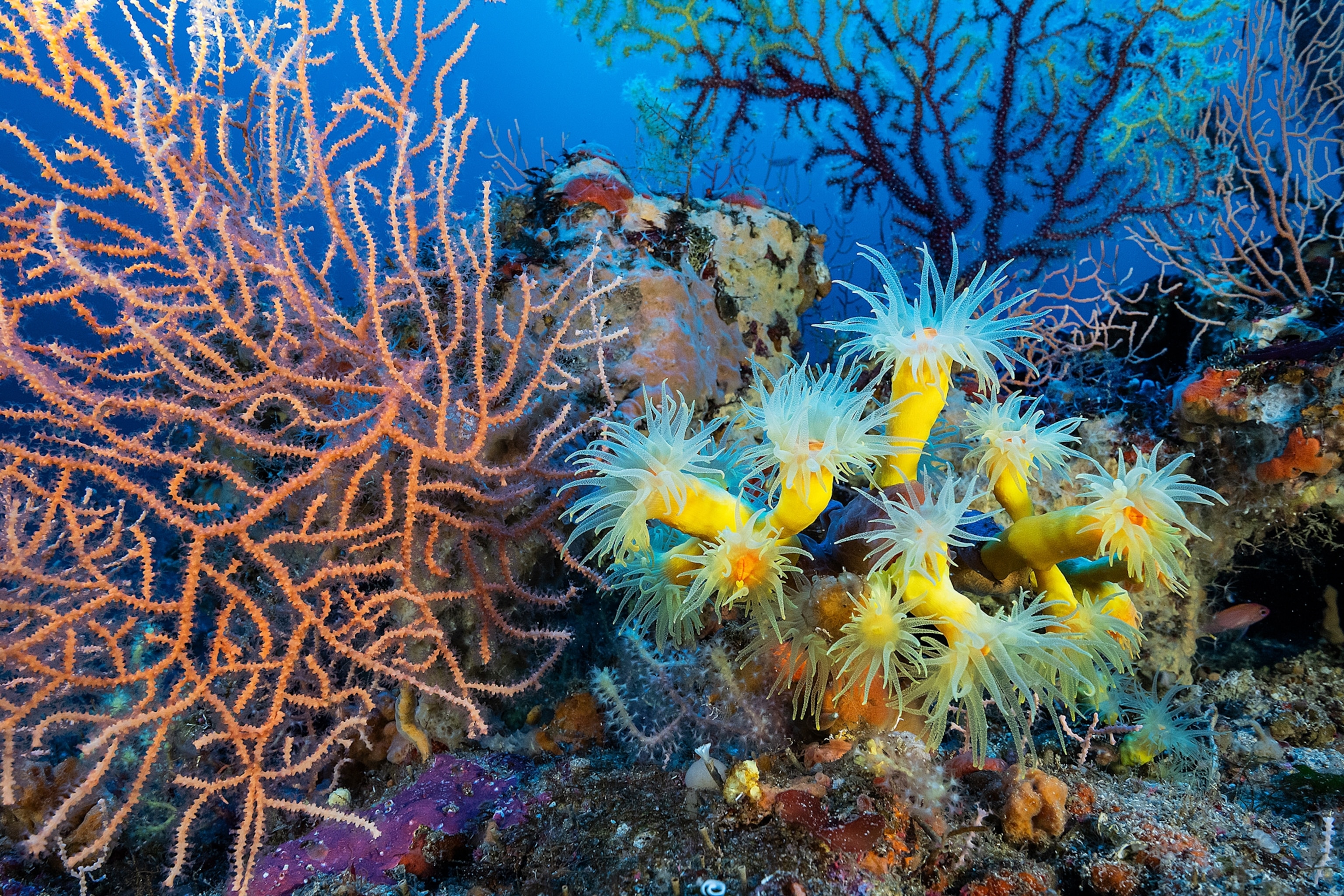

This time, the crew could spend hours exploring it. All around, the divers marveled at the abundance of life. As they made more dives, when weather conditions allowed, they found rarely seen yellow corals in the deep canyons. There were also squat lobsters and colorful small fish hiding among pale pink gorgonians, the sort of fanlike soft corals that are usually seen in deep Mediterranean canyons. At one point Ballesta spotted a blue sea slug wandering about and took a photo. It was the first still photograph taken of this species by a diver.

(These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way.)

Ballesta invited the Pergents to monitor their progress aboard the support ship. “They looked very happy and touched that their discovery made this project happen,” he says. Because of the Pergents’ work, he and his colleagues were exploring a pristine and unusual ecosystem. But Ballesta knew this little universe was in a precarious position: It existed under shipping lanes, and commercial ships dropping anchor could pulverize everything. “Anchors can destroy all the rings very easily,” Ballesta says. The threat fueled a sense of urgency: The more they could learn about the rings, the better chance Ballesta might have of getting French authorities to protect them.

Ballesta and his team made a total of six descents from their pressurized chamber to the rings. They focused their attention on drilling cores of the rings’ central knobs, which were then sent for carbon dating analysis. The hope was that knowing the rings’ age could help solve the mystery of what formed them and how.

When the results came back, the team was shocked. The most ancient material, deep in the center of the knobs, was about 21,000 years old. For those who study climate history, that particular era represents a moment of profound planetary change. “It’s the last glacial maximum,” says paleoclimatologist Edouard Bard of the Collège de France, who organized the carbon dating. That was the peak of the last ice age.

Back then, the Mediterranean was colder and far shallower, and the place where the rings are today would have been less than 65 feet from the surface, bathed in sunlight.

In the summer of 2023, Ballesta returned to the rings, this time with a support vessel capable of launching two submarines to allow ocean and climate experts, including Bard, to make their own extended voyages into the ecosystem. The effort, which received funding from the National Geographic Society, was intended to form a scientifically rigorous hypothesis of exactly how the circles emerged.

On one dive, Ballesta swam alongside the submersible as it scooted above the seabed. Acting as a tour guide, he showed the scientists inside various aspects of the rings and their surroundings. There were underwater caves nearby, set into a small cliff. The divers had found several caverns with layers of sediment that confirmed the area had once been situated above the ancient coastline—the voids may have been first cut through erosion as water washed against the cliffs some 21,000 years ago.

Near the end of the trip, the scientists retreated to the ship’s cabin. Hooked up to the glitchy internet, Bard and the others were reading papers, looking at maps, thinking over what they’d seen. Slowly, over the next few months, they put together a hypothesis.

Even though, to a nonexpert, the knobs in the center of the rings might look like coral, they were not. They were deposits formed by coralline algae, photosynthetic organisms that create skeletons made of calcium carbonate. During the last ice age, thousands of these algae colonies likely took root on what was then a very sunny seafloor.

For 3,000 years or so, these algae flourished, growing outward like domes or pancakes measuring several yards. Then, around 20,000 years ago, the world began to warm and continental ice sheets began to melt, funneling into the Mediterranean, which rose until the sun-loving algae were drowned in darkness. Their domes collapsed, leaving only the central knobs and bits of calcium carbonate scattered like bones from a carcass around them. For thousands of years, nothing lived amid the remains that left a permanent imprint.

But about 8,000 years ago, the sea level stabilized. Deepwater algae laid down new layers on the central knobs, creating the film of life the divers saw. At the same time, rhodolith algae started to encase broken bits of calcium. The nuggets of algae rolled downhill from the knobs, settling around the base of the cones in perfect circles. That’s everyone’s best guess: The simple tug of gravity formed the rings.

(We finally know what caused Florida fish to spin in circles until they died.)

“We don’t have all the proof,” admits Ballesta. “But we have nothing to say our history is wrong.”

Protecting the entire field of rings may prove difficult. Only about one-third of them lie within the Cap Corse and Agriate Marine Natural Park, a French marine protected area. But the park, with help from Ballesta’s Andromède Océanologie, is taking on this challenge. Using data from Ballesta’s dives, it plans to advocate for the further protection of all rings, even those located outside its bounds, in French and Italian waters. The park’s management council will propose prohibiting the anchoring of commercial vessels in the area.

“Normally with this type of regulation, it takes years,” Ballesta says. But because so many of the rings already exist within a conservation zone, he’s optimistic. He’s also no longer thinking just about the rings but about what they represent. Traces like these—signs of the ancient coastline, including rings, submerged caves, and other mysterious structures—may be hidden all around the ocean floor. They are places for studying how the world is always building something new on the husk of a previous age.

While there have been no sightings of the rings elsewhere, “you have to realize that explorations at this depth have been rare in the Mediterranean Sea,” Pergent-Martini says. “Perhaps there are others that have not yet been discovered.”

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Laurent Ballesta’s work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers at natgeo.com/impact.

Veronique Greenwood, a northern England-based science writer, reports often on plant and animal adaptations and recent discoveries in the ocean.

Laurent Ballesta, a French diver, photographer, and marine biologist, spent weeks living in a pressurized chamber that enabled him to withstand more time at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea for this story.