What to know about the link between tattoo ink and cancer risk

Mounting evidence suggests tattoos are linked to elevated cancer risk.

While tattoos continue to become ever more prevalent, recent years have brought a steady drumbeat of scientific studies linking tattoo ink to an elevated cancer risk—findings that might give you pause if you’re thinking about getting one.

One such study, published in a 2024 issue of The Lancet, found that people with tattoos had a 21 percent higher risk for lymphoma, or cancer that affects the lymphatic system, an important part of the body’s immune system. Another study of nearly 2,700 twins in Denmark, published in the January 2025 issue of BMC Public Health, found that people who had tattoos had a 62 percent increased risk of developing skin cancer and a nearly three-fold increased risk of developing lymphoma with large tattoos.

These studies are far from conclusive. While they have found correlations between tattoos and an increased risk of cancer, they haven’t proven causation. And there is some conflicting evidence: A study in the December 2025 issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that people with three or more large tattoos had a 74 percent lower risk of melanoma, the most serious form of skin cancer, than those who were tattoo-free.

(The curious link between Alzheimer’s disease and cancer.)

Still, this new research raises interesting questions about what tattoo ink does once it’s inside the body—and how various risks enter the picture. And it’s more important than ever for scientists to answer those questions: According to a 2023 survey by the Pew Research Center, 32 percent of adults in the U.S. revealed that they have a tattoo and 22 percent have more than one.

“People should not panic but they should better understand the nature of tattoo ink and the types of heavy metals and other carcinogens in those inks,” says Christopher Bunick, an associate professor of dermatology at the Yale School of Medicine.

Whether you already have a tattoo or are thinking of getting one, here's what scientists are learning about the long-term effects tattoo ink can have on the immune system, whether the size of a tattoo matters—and why getting one removed isn’t the answer.

Mysterious mechanisms behind the link

Experts don’t fully understand the underlying mechanisms linking tattoos to an elevated cancer risk, but there are several widely accepted theories about what may be going on.

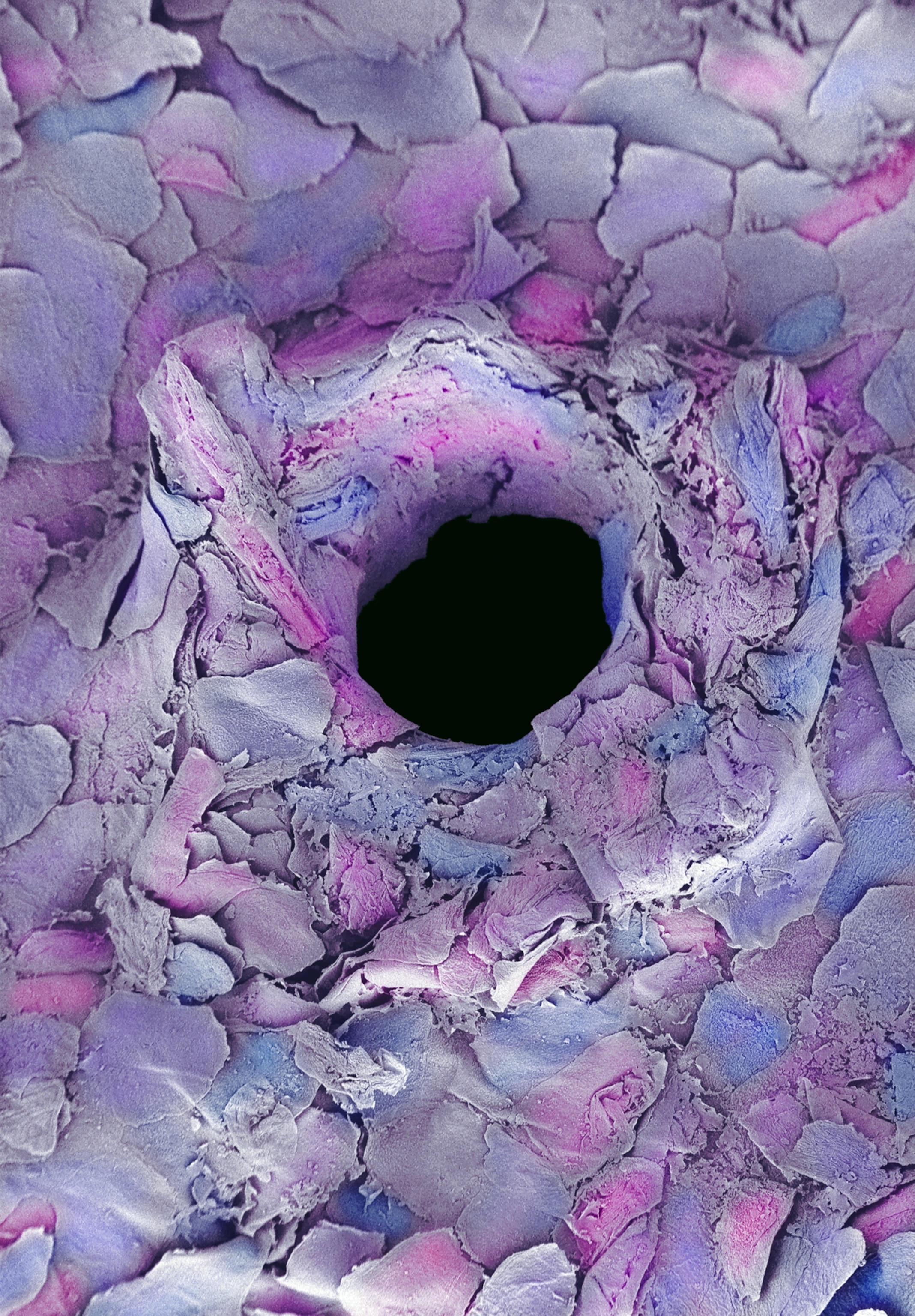

For one thing, even though tattoos appear on the skin, they are more than skin deep. When ink is injected deep into the skin, over time tiny particles can travel through the lymphatic system and end up in the lymph nodes; this can lead to hidden inflammation.

“Your body recognizes the ink as foreign substances and activates the immune system to try to remove it,” explains Christel Nielsen, coauthor of the Lancet study and a researcher in the division of occupational and environmental medicine at Lund University in Sweden.

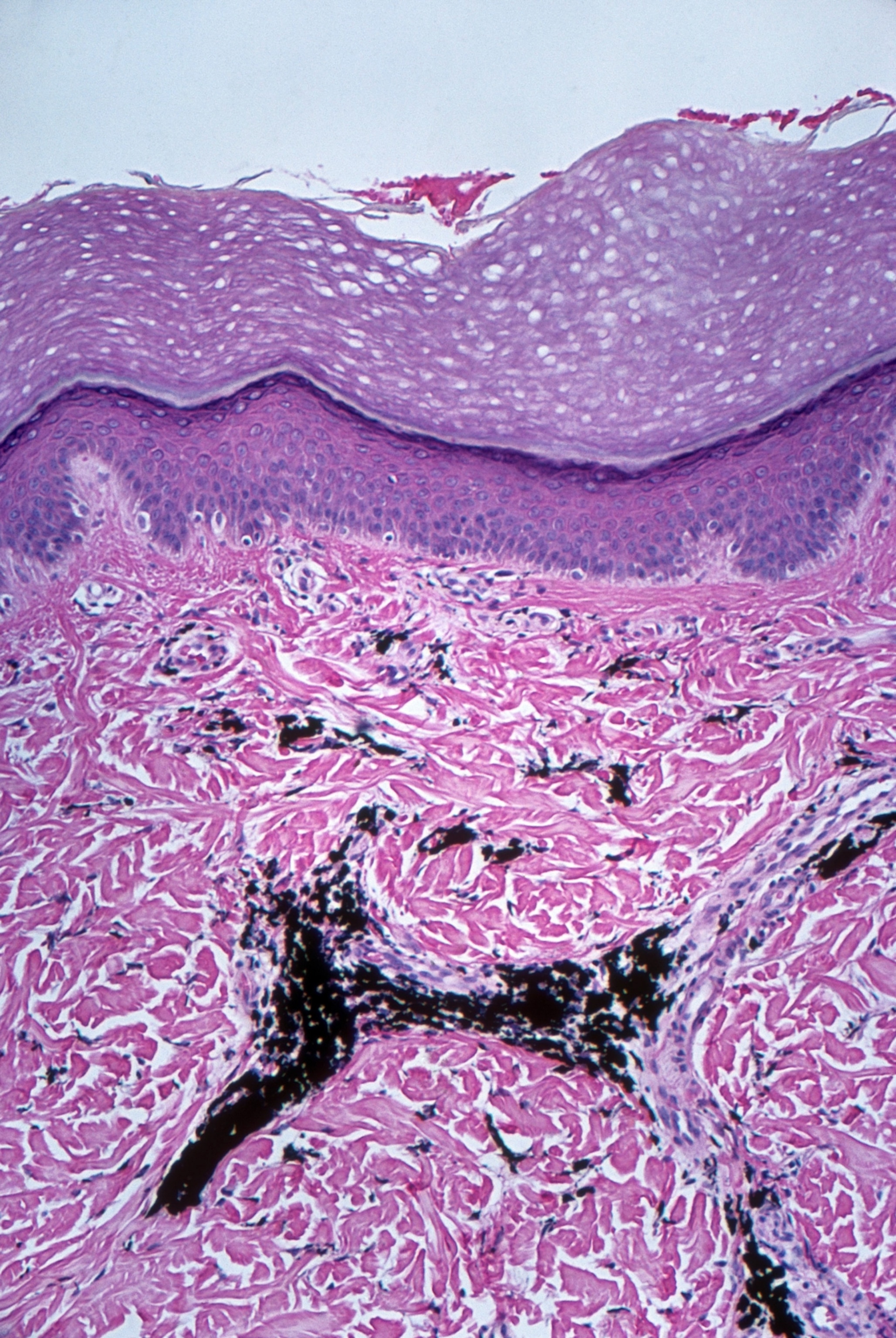

In a study in a November 2025 issue of PNAS, researchers gave mice tattoos on their footpads, using black, red, and green ink, then monitored how the ink was transported by the lymphatic system and accumulated in lymph nodes. They found that the ink is retained in certain immune cells called phagocytes within lymph nodes, and the phagocytes die and trigger a long-term inflammatory response. What’s more, when the mice were given two different types of vaccines (for COVID-19 and influenza), the tattoo ink at the vaccine injection site altered the immune response to the vaccines.

There are other factors at play. For one thing, tattoo inks contain various chemicals and some of these may be carcinogenic, meaning they’re linked to causing or increasing the risk of cancer. For example, black inks may contain chemicals called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which may increase cancer risk, and red ink may contain azo dyes that can break down into compounds that may cause cancer under UV light exposure, says Matthew Cortese, a lymphoma specialist at the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York.

(Colon cancer is rising in young people. Finally, scientists have a clue about why.)

In addition, some tattoo inks may contain heavy metals—such as lead, cadmium, mercury, and others—that are known to be toxic, as well as solvents and other additives like formaldehyde and phenol, which are associated with allergic reactions, notes Kelly Johnson-Arbor, a physician and toxicologist at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C. “

“This deposition of ink and metals triggers three responses that are well-recognized risk factors for cancer—chronic immune [system] activation, oxidative stress, and abnormal growth of white blood cells called lymphocytes,” says Joe K. Tung, medical director of Falk Dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Oxidative stress, which may be triggered by introducing foreign substances into the skin from tattoo ink, can damage tissue and increase cancer risk; by contrast, when lymphocytes grow in an uncontrolled way, they can turn into cancerous cells and tumors can form.

Some of the effects can be long-lasting. When “microscopic pigment particles and metal contaminants travel through lymphatic channels to our lymph nodes, they can accumulate and persist for decades,” Tung says.

Timing—and size—may matter

Because the ink and other substances in tattoos can take up long-term residence in the lymph nodes, there can be a cumulative effect from them over time. The Lancet study, for example, found a U-shaped curve to the risk of developing lymphoma: It was highest during the first two years after getting a tattoo then decreased from years three to 10 before increasing again after 11 years.

Unfortunately, the potential cancer risk doesn’t seem to hinge on the era in which someone got a tattoo. “Ink today is not safer than it used to be because tattoo vendors get their inks from innumerable sources, without clear quality control regulations or composition transparency with clients,” Bunick says.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration considers tattoo inks and pigments to be cosmetics and color additives so it doesn’t pre-approve or closely regulate these products. If safety or contamination issues are reported, the FDA will investigate these claims but “recalls of contaminated tattoo ink products are rare,” says Johnson-Arbor.

(The ancient history of tattoos—revealed by inked-up mummies.)

Which means the onus is on consumers who are interested in getting a tattoo to research and choose reputable tattoo vendors, ask about the chemical composition of the inks that are used, and request to see safety documentation about them, Bunick says.

The question of how tattoo size affects your cancer risk is a little trickier. The 2024 study published in the Lancet found no evidence that tattoo size put people at greater risk of lymphoma. However, the 2025 study suggests that those with tattoos bigger than the palm of a hand had a nearly three times higher lymphoma risk than non-tattooed participants.

“In our study, tattoo size does appear to matter—a reasonable interpretation is that larger tattoos reflect a higher overall exposure to ink,” says study coauthor Signe Bedsted Clemmensen, a scientist in the Research Unit for Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Biodemography in the department of public health at the University of Southern Denmark. “The more ink that enters the body, the greater the potential for accumulation in lymph nodes and for prolonged interaction with the immune system.”

However, Clemmensen adds that “tattoo size is only a rough indicator. Two tattoos of the same size can differ greatly in density and how much ink they contain.”

Protective measures

Despite these worrisome findings, it’s important to remember that correlation isn’t the same thing as causation. More research needs to be done to figure out the role tattoos may have in this picture, experts say.

“Many confounding factors in real life—including lifestyle, UV exposure, occupational hazards, and immune status—can influence cancer risk,” says Tung. “As with many environmental exposures, tattoo-associated cancer risk is likely cumulative and modified by other behaviors that can augment or mitigate some of these risks.”

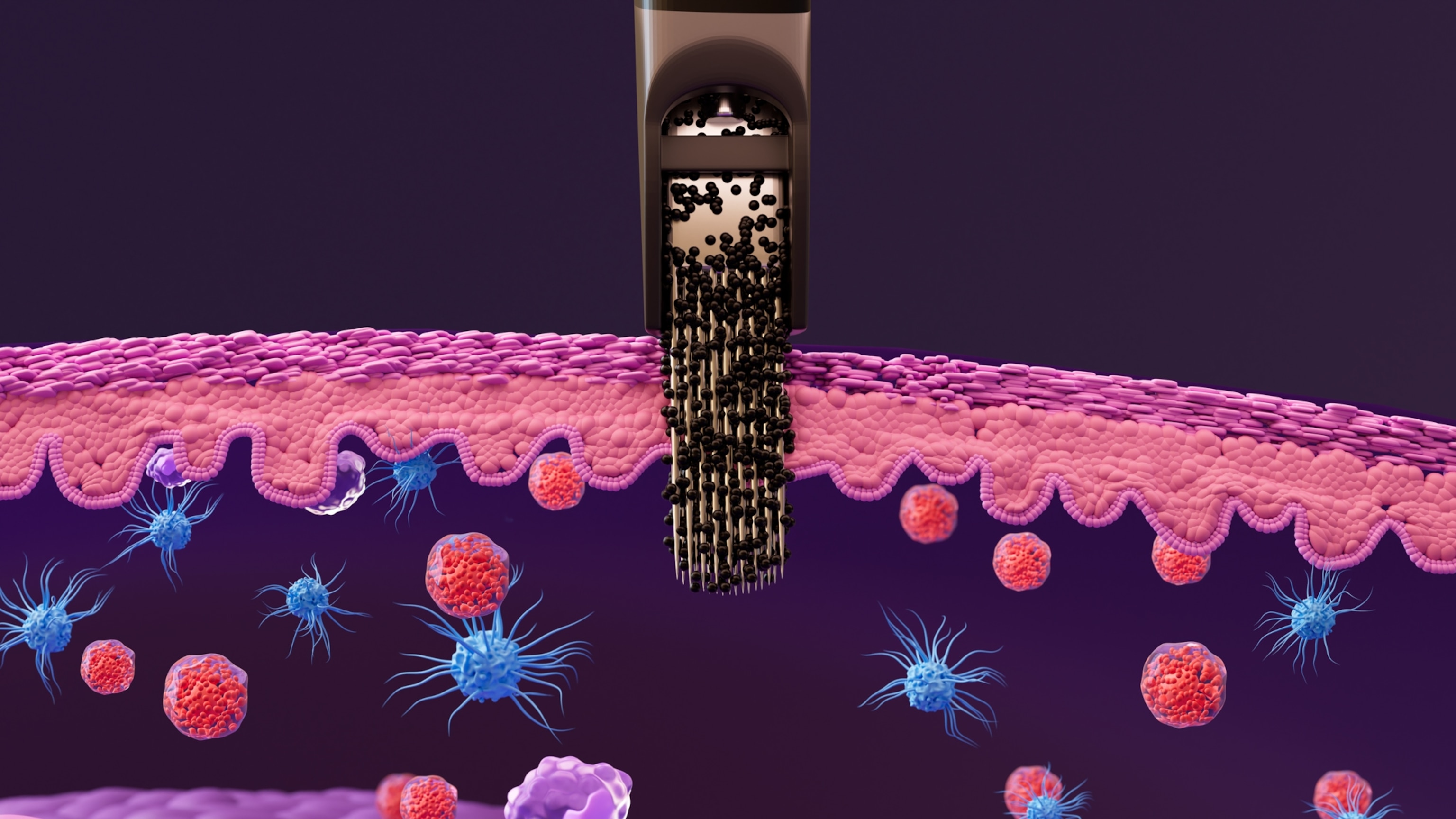

This much is clear: Having a tattoo removed isn’t the solution. In fact, it may actually increase cancer risk. Laser treatment is the most common method for tattoo removal, and it “increases the fragmentation of the ink pigment particles and may [enhance ] migration of carcinogenic compounds to the lymph nodes,” explains Bunick. In fact, the Lancet study found that people who had laser treatment for tattoo removal had a two-and-a-half-times higher risk of lymphoma.

A better approach: Be proactive about following a healthy lifestyle. This includes consuming a wholesome diet, avoiding smoking, exercising regularly, limiting alcohol consumption, and protecting your skin.

“It’s especially important for tattooed individuals to protect their skin from the sun, either by using sunscreen or even better by covering tattoos with clothing,” says Nielsen. Look for broad-spectrum sunscreens with an SPF of 30 or higher, Tung advises.

(How much SPF is enough? Your burning questions about sunscreen, answered.)

People with tattoos should also schedule regular skin examinations by a dermatologist to look for possible signs of skin cancers as sometimes it can be hard for the average person to see worrisome skin growths within a tattoo.

Also, be sure to have regular check-ups with your primary-care physician. Be on the lookout for unusual masses or lumps and swollen lymph nodes and get these checked out promptly, says Cortese. When detected early, skin cancers can often be removed, and lymphomas are highly treatable and often curable.

Above all, it’s important to keep these potential risks in perspective, says Clemmensen. “Lymphoma is a relatively rare cancer, and even if there is an increased risk, the absolute risk for any individual remains low.” Some people may consider this added risk a small price to pay for having body art.