Scientists are learning how to interrupt pain before it forms

New research suggests pain is not a simple signal of injury but a process that unfolds across nerves, spinal cord, and brain. Scientists are now targeting earlier points in that pathway, before pain fully forms.

One in ten people worldwide now lives with chronic pain—a condition medicine still struggles to treat without creating new harm. After the collapse of the “pain-free” promise that fueled the opioid crisis, doctors are rethinking what pain actually is—and where it can be changed.

Nearly 20 years ago, pediatric anesthesiologist and researcher Amy Baxter began exploring that question by poking people in the arm with a toothpick—on sidewalks, at dinner tables, wherever she could recruit a volunteer. “Tell me when the sensation turns from sharp to dull,” she’d say, while holding a vibrating device against their skin until the sensation changed and writing down their data.

Today, pain is no longer understood as an on–off switch to be flipped, but as a dynamic conversation between the body and the brain. Sensory signals are shaped by context, memory, and emotion, and those signals can be amplified, muted, or redirected at multiple stages.

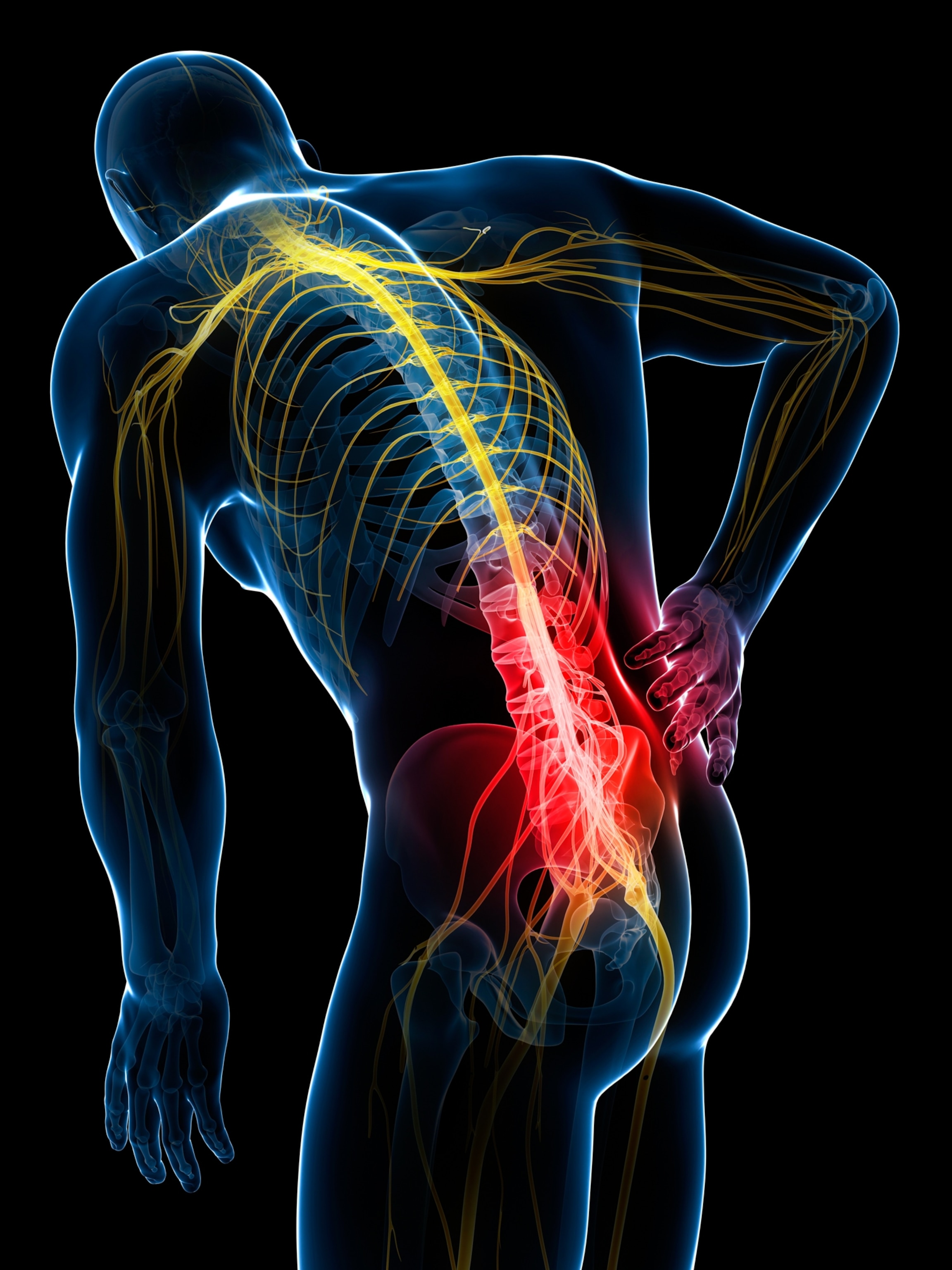

For decades, pain medicine has focused on what happens after pain reaches the brain. A new wave of research is shifting attention earlier, to sensory nerves, where nociceptive signals can be altered before the brain constructs pain at all.

Pain forms in the brain

Before pain is perceived, it begins as nociception, the detection of potential harm by specialized sensory nerve cells called nociceptors. These peripheral neurons extend long, branching fibers through the fascia, skin, muscles, and internal organs, where they’re tuned to detect extremes: heat or cold, pressure, friction, impact, chemical irritation.

When activated, a nociceptor fires off an electrical message to the spinal cord, where it’s translated from electricity into molecules and dispatched to the brain. It first reaches the thalamus, which functions like the brain’s switchboard. This is where feeling an injury actually begins.

For more than 40 years, University of Toronto neuroscientist Michael Salter has studied this dialogue between the nociceptive system and the brain, from the physical pathways of pain transmission to the genetic reasons why pain differs between men and women.

(Painkillers don’t work as well for women. Here’s why.)

When Salter started out, he says, “The pain field was kind of a backwater. Pain people, I think, were considered just ‘odd.’” But especially since the arrival of functional MRI in 1999, which enabled scientists to watch pain unfold in the brain for the first time, “the richness of understanding of pain has changed quite dramatically.”

One of the most important realizations is that pain is not a direct readout of tissue damage. “It’s like beauty,” Salter says. “Beauty isn’t photons hitting your retina. There’s a lot more to it that the brain gets involved in.” Nerve signals, like the photons, provide raw input, but perception is constructed. “When you ask people, ‘Where’s the pain?’ they’ll say, ‘It’s in my hand,’ or ‘It’s in my back,’” Salter says. “It’s not there. It’s in your brain.”

What a person experiences when nociceptive signals reach the thalamus depends on what their brain does next. The thalamus may recruit attention, emotion, memory, and fear—physiological dimensions of pain that make it feel worse—by design. This is why some researchers say that “all pain is psychological.”

But this isn’t the type of psychology one can control, Baxter explains. They’re the products of neurotransmitters, programmed to help a human survive by activating pain as a means of training a human to avoid danger. Pain is a security system—designed to be so complex it is impossible to override. A painkiller may disrupt this system’s operation, but only temporarily.

Fear of pain, in particular, lays down tracks in the brain called neural pathways that carry alert signals from an injury site long after the injured tissue has healed. This continuous echo of pain can lead to a domino effect of changes in movement, reduced blood flow, and muscle weakness—changes that, together, bring about chronic pain.

(How scientists are unraveling the mysteries of pain.)

“Everybody who’s in science or went to medical school had to take a multiple-choice test, so people want a single, right, answer,” Baxter says. “And with something like pain or the immune system, there simply isn't one. You can override it short-term, but it’s going to adapt.”

Pain researchers see that adaptability as an opportunity. Throughout the nociceptive system, there are multiple points where signals can be dulled, scrambled, or outcompeted—well before the brain decides whether a bad feeling is safe, or whether it means danger. Topical analgesics take advantage of this pre-pain window by cutting off shallow, surface-level signals of “ouch.” Baxter wondered whether deeper pain could be addressed similarly.

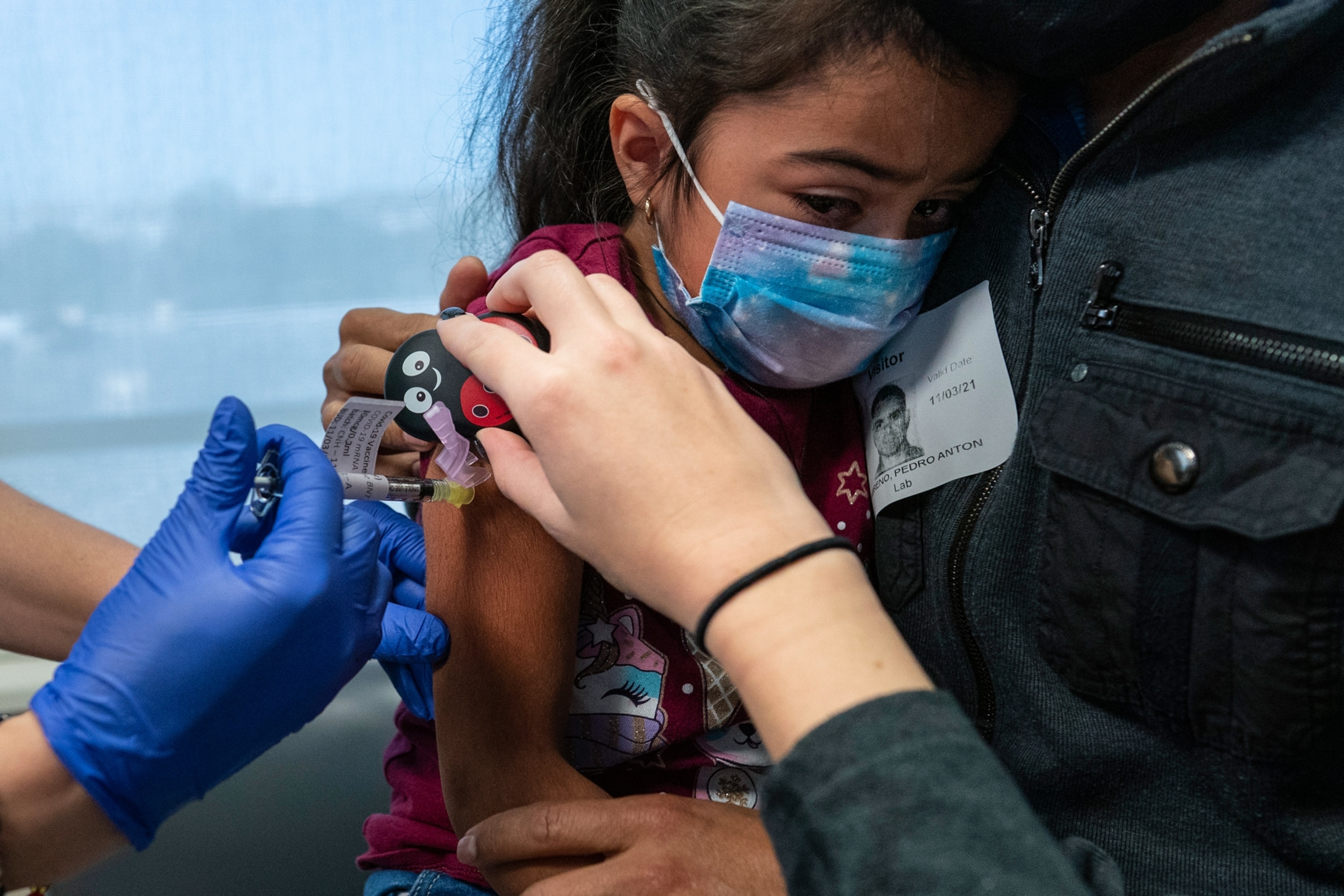

Her early experiments—including the journey of the toothpick—grew out of a practical pursuit: Could she make routine needle procedures less painful for children?

Previous research showed that vibration activates a different set of sensory nerves: mechanoreceptors, which detect gentle sensations such as motion, stretch, and light touch. Their messages to the brain compete with nociceptive pain signals at the spinal cord. Each mechanoreceptor responds best to specific vibration frequencies, suggesting that stimulation could be fine-tuned.

Baxter tested different frequencies of vibration to activate the right mechanoreceptors, then paired that vibration with cold, which engages dopamines—part of the body’s built-in pain-modulating chemistry. The combination doesn’t eliminate pain, but it does temporarily block nociceptive signaling—an effect best suited to localized, acute pain. Through other pathways, it has potential for certain types of chronic pain, too.

Across controlled clinical trials pairing vibration and cold, researchers around the world have found that combining the sensation of cold (which activates the body’s natural, endogenous opioid system) and specific frequencies of vibration (which stimulate sensory nerves) reduces the pain of needle procedures, and in some cases, makes it not hurt at all.

The implication was larger than vaccines. “If we can do this with something as intense as a needle, maybe we can manipulate what different frequencies are coming in from different places,” Baxter says. That line of thinking opened a new avenue for pain research—one focused not on eliminating sensation, but on reshaping how pain signals enter the system.

Not just needles

Twenty-five-year-old screenwriting student Sara Wright lives with chronic pain. She writes episodic comedies, but this year, her lower back pain has made it difficult to find the humor. Her first back surgery, six years ago, corrected vertebrae that were rubbing together, and she sailed through the recovery. Within six months, she was able to run a mile.

Wright’s second surgery, this past summer, has been a different story: “I've spent every day of this year in pain,” she says of 2025. The hardest part, she adds, isn’t the physical sensation of pain itself. “It’s the not knowing, and the not changing. That, emotionally and physically, is difficult to deal with.”

Wright has trouble sleeping, can’t think clearly, and she feels she’s lost a core part of herself. “It's hard, because that is, like, my identity—being a determined, go-getter person.” That erosion may reflect chronic sleep disruption, the constant cognitive load of pain, or side effects associated with opioid medications, which her surgeon initially prescribed for relief.

(Could this be the solution to chronic pain—and the opioid crisis?)

Working with her pain specialist, Wright began replacing opioids with other interventions. She now uses a mix of medications and integrative therapies, including a vibrating wearable designed by Baxter, called a DuoTherm.

For individuals like Wright, the costs of chronic lower back pain are impossible to tabulate. But on a public health scale, one can put numbers to it. In the U.S., patients spend more on treating chronic pain than on treatments for diabetes and cancer combined. Chronic lower back pain is the second leading reason, after cancer, for opioid prescriptions and is now the leading cause of disability worldwide. Rates of invasive interventions—spinal fusions, implantable devices—have climbed by 3,000 percent in recent years, with complications affecting as many as one in five patients. For many people, the pain evolves but never resolves.

Baxter knew this. Early in her career, she had prescribed opioids herself, before their risks were widely understood. When she began considering how to test applications of her cold-plus-vibration approach beyond needle pain, she quickly settled on the lower back. For an NIH grant focused on mechanical stimulation, she designed both the device and the study around that use case—tailoring the intervention to a form of pain that medicine has long struggled to treat.

Interrupting the transmission

By the mid-20th century, researchers were testing two ways to crowd out pain signals before they reached the brain: mechanical stimulation (from vibration) and electrical stimulation (from electric shocks). By the 1970s, vibration had fallen to the wayside.

“If you didn’t use the right [vibration] frequency, it didn’t work,” says Baxter of the early research. But over the years, it became clear that early studies discounted many variables. Many experiments tested only a single frequency and failed to account for other variables—such as duration, placement, or intensity—and often did not report those parameters at all. As a result, potentially beneficial effects were overlooked.

But in recent years, scientists have zeroed in on an important distinction. Electrical stimulation can disrupt pain signals once they are already in transit. By contrast, non-painful mechanical stimulation activates mechanoreceptors—those sensory nerves that respond to touch and movement—allowing signals to compete earlier in the pathway. Instead of merely scrambling pain messages as they arrive in the brain, Baxter says, this starts “a new conversation altogether.”

In 2025, Baxter and colleagues published a randomized, controlled study measuring her wearable mechanical stimulation. Rather than comparing it with a placebo, they measured its effects against a longstanding electrical stimulation device, a TENS unit (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation).

Consistent with earlier research, mechanical stimulation reduced pain. Participants using Baxter’s device were also significantly less likely to progress from acute to chronic lower back pain than those using electrical stimulation. The difference, Baxter says, may stem from timing: vibration engages mechanoreceptors, while mild shocks from electrical stimulation are just painful enough that the brain’s own pain inhibition system kicks in.

Wearable devices add another element: control. Adjustable settings give patients a sense of agency, which research shows can influence pain perception. But vibration works best when it is continuous, raising a new question: could mechanical stimulation ever deliver relief that lasts beyond the time that it’s actively applied?

(How scientists are using virtual reality to treat chronic pain.)

At Columbia University, biomedical engineer Elisa Konofagou is studying a different form of mechanical input: focused ultrasound. Ultrasonic waves are typically used for internal imaging. Konofagou found that, when directed at peripheral nerves, the microscopic vibrations these waves cause in the tissue appeared to nudge peripheral nerves enough to interfere with pain signals.

Sound waves have one practical advantage. They can reach peripheral nerves, which opens doors for the management of deep-rooted neuropathic pain, like carpal tunnel syndrome. In mouse studies of carpal tunnel, Konofagou’s team found that this mechanical approach may not only quell pain in real time but also dampen inflammation for days after treatment.

This longer relief “is something that we had actually seen with patients,” Konofagou says. They were only anecdotal accounts, so she and her colleagues were hesitant to take the possibility too seriously. “But then, after doing the whole study in mice, we realized, OK, this is a real effect.”

Breaking the pain cycle

In Baxter’s recent study, researchers focused on patients with chronic lower back pain that had not improved with standard care. Most people in this group had tried upwards of a dozen different interventions over their journey. ”People who had chronic pain for five years and nothing worked,” Baxter recalls.

Within about three months, nearly half of the participants—47.4 percent—using a mechanical stimulation device improved to the point that pain no longer seriously interfered with daily life, compared with 11 percent of the control group—people using a standard TENS electrical stimulator. “So, you know, fixing [this group] is pretty great, for half,” Baxter says. “But still, for half that group, it didn’t work,” she says. What different frequencies might their pain respond to?

(How you can change your body's threshold for pain.)

Seventy-year-old Loren DeRoy wasn’t part of Baxter’s study—but in the real world, she falls into this “nearly half” group. DeRoy’s back pain began in her early 40s, after years of tennis and horseback riding, compounded by underlying degenerative disc disease, stenosis, and recurring sciatica.

Over the coming years, intermittent pain turned into a daily presence. Aware of a family history of addiction, she declined the offer of an opioid prescription, even after multiple surgeries, including a lumbar operation, a knee replacement, and hip surgery.

She tried physical therapy, stretching, massage, hot tubs, acupuncture, anti-inflammatories, and, at times, gabapentin, which dampens nerve signaling. A couple of years ago, she also started using a DuoTherm.

DeRoy can pick different vibration frequencies and combine them with heat or cold to modulate pain signals. Those inputs may also influence muscle tension and inflammation, though the precise mechanisms are still being studied. For DeRoy, the effect has been tangible.

“Being able to interrupt that pain with a medical stimulation—however it's working—has been amazing for me,” she says. “Being able to sleep at night, feeling good when I wake up. I lost maybe 25 pounds just because I’m not in chronic pain.”

Her doctors tell her that, based on imaging, her arthritis is worsening, she says. But after decades of pain and combining interventions to address it, finally, “something interrupted that idea of being in daily pain.” That shift has compounding benefits. She’s taking her dog for longer walks, she says. She’s moving more. “And that always helps with arthritis.”

There is no one-stop shop for stopping pain if nerves are still firing pain signals, Baxter emphasizes. The survival system is too complex. But restoring what pain takes away, as DeRoy did, unlocks the door. “The transmission is such a tiny little part of it, but that part matters,” Baxter says. “It convinces your body that it's safe to move again…and movement is the medicine.”