Heavy drinking linked to deadlier brain hemorrhages

A new study found that habitual drinkers were more likely to develop earlier strokes and larger brain bleeds.

It’s long been known that heavy drinking raises blood pressure and damages the liver. But new research suggests it may also deal a devastating blow to the brain—causing life-threatening hemorrhagic strokes.

The study, published November 5 in Neurology, found that people who consumed three or more alcoholic drinks a day experienced bleeding strokes inside the brain an average of 11 years earlier than light or non-drinkers—and faced worse outcomes such as larger bleeds, greater brain damage, and higher mortality.

(Strokes are on the rise—and these are the reasons why.)

“Heavy alcohol use may not only increase the risk of having a brain bleed at a younger age, but may also worsen the underlying damage when one occurs,” says Edip Gurol, lead author of the study and director of the Hemorrhage Risk Stroke Prevention Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The research was observational—meaning it doesn’t prove causation—and relied on self-reported alcohol use, which makes it possible to underestimate actual drinking levels. Even so, its findings are helping researchers fill previously missing gaps. “This is a very valuable study that adds to what we know about how alcohol affects the brain,” says Faye Begeti, a practicing neurologist at Oxford University Hospitals in England, who was not involved in the research.

Here’s how the study fits into broader research on alcohol’s impact on the brain and body—and where the science goes from here.

How alcohol damages the brain

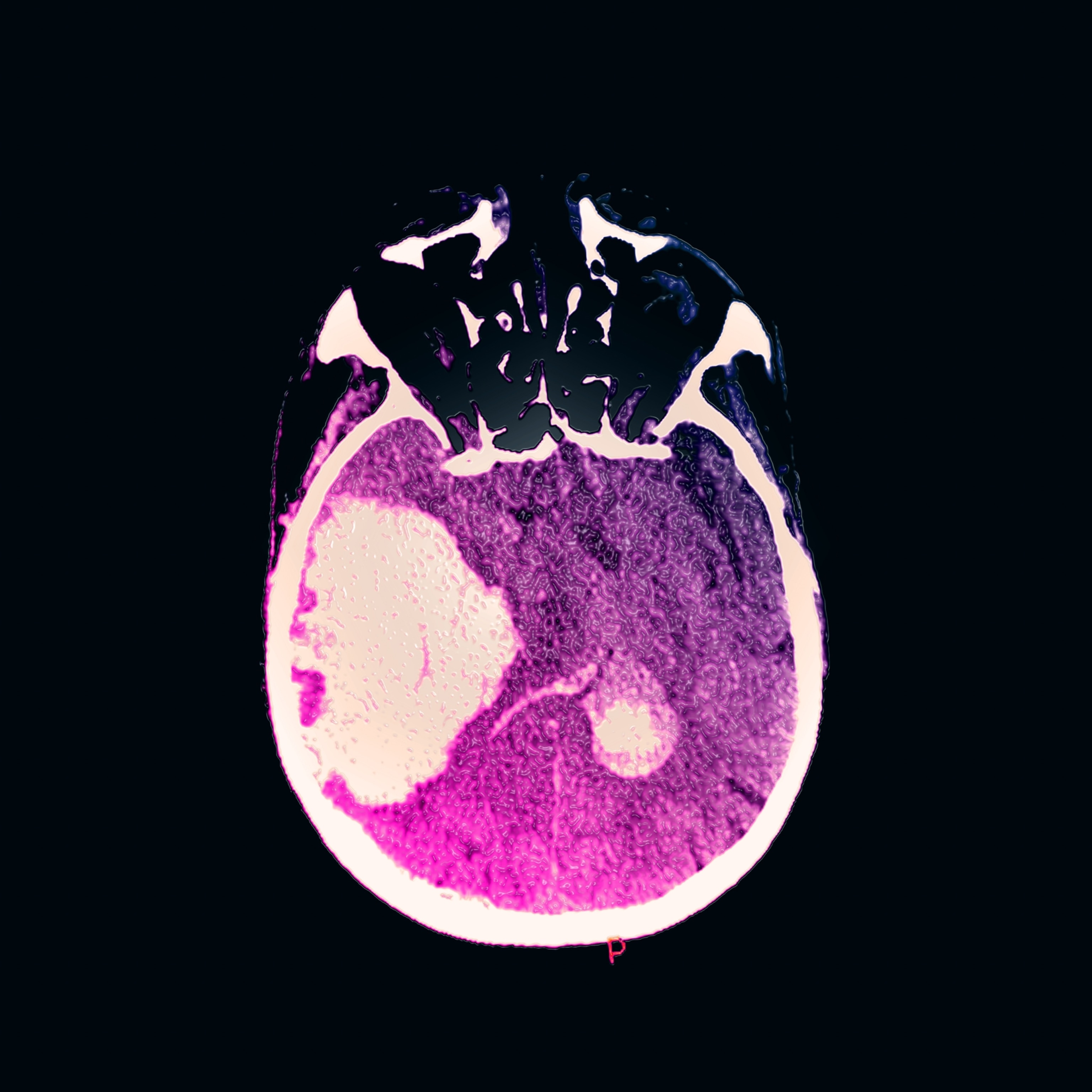

Hemorrhagic strokes—also known as intracerebral hemorrhages (ICH)—occur when a weakened blood vessel ruptures and bleeds into surrounding brain tissue. They account for only 10 to 20 percent of all strokes annually, but are far deadlier and more damaging than the more common ischemic type.

“Roughly 30 to 40 percent of people who experience intracerebral hemorrhages die, and many survivors live with lasting disability,” says Kevin Sheth, director of the Yale Center for Brain & Mind Health and chair of the American Heart Association’s Hemorrhagic Stroke Group, who was not involved in the study.

Heavy drinking increases the risk of ICH through several overlapping mechanisms. One is that "alcohol accelerates brain atrophy—meaning the brain shrinks slightly while the skull remains the same size, stretching delicate veins and making them more likely to rupture, even with minor trauma," explains Begeti.

(Eight things we’ve learned about how alcohol harms the body.)

Alcohol also destabilizes blood pressure, impairs platelet function (the blood cells that help form clots), and damages the liver, which disrupts normal clotting. Over time, it can also directly injure small cerebral vessels—leading to microscopic leaks or “microbleeds” that weaken vessel walls. “The net effect is a greater tendency to bleed—and to bleed more severely once a hemorrhage begins,” Sheth says.

Inside the new research

The study analyzed more than 1,600 patients admitted to Massachusetts General Hospital between 2003 and 2019 for spontaneous, non-traumatic brain hemorrhages. About 7 percent were classified as heavy drinkers—those who regularly consume three or more alcoholic drinks a day.

These heavy drinkers were shown to experience hemorrhages about 11 years earlier than their lighter-drinking counterparts—on average, age 60 versus 71. The researchers believe this accelerated timeline is linked to alcohol’s effects on vascular aging and blood vessel fragility.

For instance, compared with light or non-drinkers, these patients had higher blood pressure and lower platelet counts. "Importantly, the brain scans also showed more small-vessel damage and disease," adds Begeti.

The imaging further revealed that heavy drinkers had larger hemorrhages and more frequent intraventricular extension—bleeding that spreads into the brain’s fluid-filled spaces, which is a marker linked to higher mortality. “Together, these findings highlight that heavy alcohol use appears to accelerate vascular aging in the brain,” says Begeti.

While past research has hinted at the connection between heavy alcohol use and vascular aging in the brain, Gurol notes that most earlier studies lacked detailed imaging to reveal the biological mechanisms behind why. “This is the largest study to include CAT scans of the brain in all patients and MRIs in about 75 percent,” Gurol says. This allowed the team to identify structural brain changes and better understand the ways alcohol contributes to bleeding risk.

Clifford Segil, a neurologist at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica who was not involved in the research, says the findings make clear that heavy alcohol users who experience bleeds “are going to get bigger bleeds, and their potential for recovery will be decreased due to alcohol’s effects on blood pressure and platelet levels.”

Such findings, adds Sheth, “are timely and clinically relevant.”

The takeaway

But like all observational research, the study cannot prove cause and effect. “Randomized controlled trials—the gold standard for proving causation—aren’t feasible when studying heavy drinking because we obviously can’t assign people to drink heavily to see how it causes harm,” Gurol explains.

The team also relied on self-reported alcohol use, which can be unreliable. “It’s possible that some heavy drinkers—or their families—may have underreported alcohol use, meaning a few could have been misclassified as non-heavy drinkers,” Gurol says. “That kind of underreporting would likely dilute the true impact, so the real effect may be even stronger than what we observed.”

To strengthen future work, Gurol suggests that additional research "should involve larger patient groups, paired with high-quality brain imaging as we had, but with more precise, prospectively collected data on drinking habits.”

Until then, the takeaway is clear. “This study adds to the growing evidence that alcohol use offers no medical benefits and underscores how worrisome chronic alcohol use can be,” says Segil.

(Alcohol is killing more women than ever before.)

Beyond brain bleeds, “heavy drinking harms almost every organ in the body," Gurol, notes, raising the risk of accidents, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, liver disease, heart disease, several cancers, and cognitive decline.

Conversely, cutting back brings measurable benefits such as lowering blood pressure (often within weeks), improving liver and heart health, and reducing the risk of stroke and microvascular brain damage over time.

That’s especially important because treatment options for some stroke types remain limited. “We don’t yet have proven acute treatments that can improve outcomes once a hemorrhagic stroke occurs,” Gurol emphasizes. “This makes prevention absolutely critical."