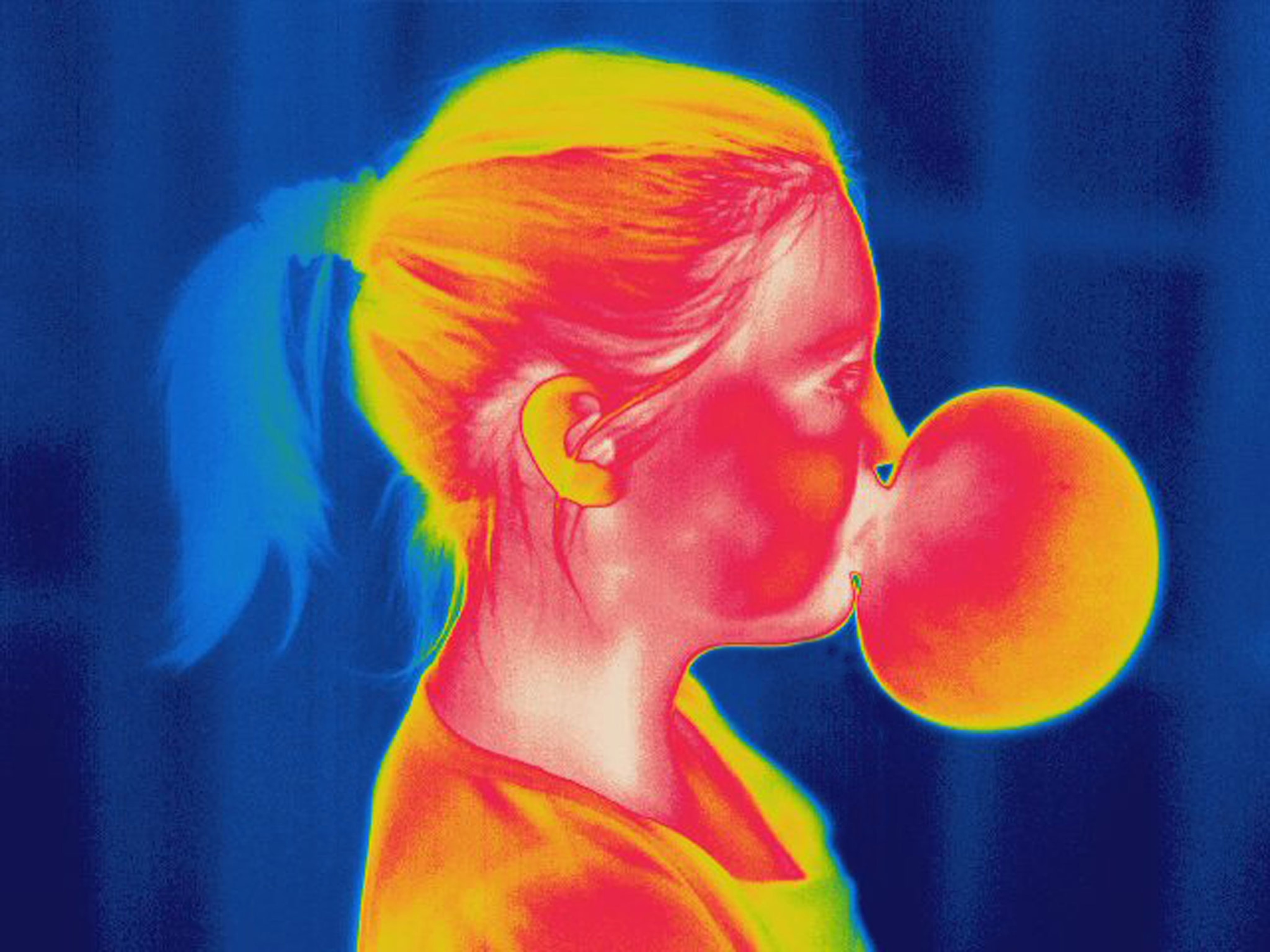

Chewing gum has a mysterious effect on the brain

Gum makers have claimed, for decades, chewing is good for your mental health. They’re kind of on to something.

While tens of thousands of businesses went bankrupt during the Great Depression, William Wrigley Jr. continued to make money. “I guess people chew harder when they are sad,” Wrigley said, whose chewing gum empire created Juicy Fruit and Spearmint. Though many people reach for gum to freshen their breath, in the early 20th century, gum also promised to calm you down. “It steadies nerves,” according to one of Wrigley’s advertisements from 1918.

This marketing strategy is now making a comeback as companies try to boost gum sales. Over the last five years, people have stopped chewing. Sales declined during the pandemic, dropping by almost a third in the U.S., and some classic gums have been discontinued, like Fruit Stripe. To combat the decline, gum companies are once again pitching gum as a salve for the mind, rather than for the mouth. New ads instruct people to “chew through” their problems, or promise gum can quiet intrusive thoughts.

Wrigley was a marketing maven; his sales pitch wasn’t exactly based on established science. Yet he seemed to stumble upon something surprisingly real about the soothing qualities of gum that is still true today.

When scientists have investigated the cognitive effects of gum, they’ve found that chewing does seem to help with attention as well as reduce stress in people who regularly chew gum. But a mystery has eluded them: why do we like chewing gum to begin with?

It’s confounding: Though the flavors can be enticing, gum has no nutritional value, and people often keep chewing once the taste is gone. There seems to be something about the basic act of chewing itself that is appealing, and a potentially easy way to relax or improve your thinking. How could the motion of moving the jaw change how you feel?

How chewing gum took over the globe—and became an early wellness trend

Humans have created gum for themselves to chew for thousands of years, and the practice has been documented all over the globe, in diverse cultures. One of the oldest chewing gums ever found was from roughly 8000 years ago in Scandinavia, made of birch bark pitch. There, hunter-gatherers would chew the sticky stuff to make a glue for their tools. But in this instance, tooth marks from the gum revealed that some of the chewers were children, as young as 5 years old, which suggests they could have been chewing for enjoyment–and not to make anything. The ancient Greeks, Native Americans, and the Mayans also chewed sticky substances that came from trees, like chicle from the sapodilla tree.

Gum came to the United States when a New York inventor got his hands on some chicle from an exiled Mexican president sometime in the 1850s. The inventor originally tried to turn it into a rubber substitute, and when that didn’t work, began to make chewing gum.

Wrigley played a large role in setting off the American gum trend. He started out selling soap and baking soda. Chewing gum was just a freebie he included with purchases. But in the 1890s he noticed that the gum was more enticing than his other products, and turned his focus entirely to gum.

“William Wrigley, amongst many things, was a marketing genius,” said Jennifer Matthews, an anthropologist at Trinity University and author of Chicle: The Chewing Gum of the Americas, From the Ancient Maya to William Wrigley. Wrigley created billboards that ran many miles long outside of Atlantic City. He even shipped sticks of gum to every address in the U.S. phonebook.

During the height of the gum industry in the 20th century, gum was so popular as to prompt hand-wringing articles in the New York Times. “Look up in the elevated cars or in the Subway cars, and if there is a row of young women of the saleslady class opposite you the chances rather are that they will be seen masticating in a sad sincerity, like so many cows in a row in a stable,” a journalist from 1906 bemoaned. New York’s mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, pleaded with gum companies to help with how much gum littered the streets.

Wrigley approached the U.S. military during World War I, pitching gum to help soldiers stave off hunger and clean their teeth. “And—that when you're nervous, you can chew on it,” Matthews said. “The military bought into that argument, and since then, has included chewing gum in the rations for U.S. military personnel.” Chewing gum then spread all over the world through soldiers.

With the proliferation of gum around the world, so did stories of its supposed health benefits. In 1916, one article pushed gum by writing, “Are you worried? Chew gum. Do you lie awake at night? Chew gum. Are you depressed? Is the world against you? Chew gum.” This idea lasted for decades; in the 1940s, a four-year-study at Barnard college found chewing resulted in lower tension, but the lead author couldn’t say exactly why. “The gum-chewer relaxes and gets more work done,” the New York Times wrote about the study’s results. “Chewing adds to his zest—one might say his gumption.”

What modern science says about chewing gum and the brain

Wrigley’s legacy in circulating the benefits of gum persists. In 2006, the Wrigley Company created the Wrigley Science Institute to fund experiments and PhD positions to investigate the benefits of chewing gum, though researchers did experiments in their own labs and published results in peer-reviewed journals. Andrew Smith, a psychologist at Cardiff University, researched gum for around 15 years, sometimes funded by Wrigley.

Studies that are funded by industry tend to have more favorable results. But Smith said that his and his colleagues’ studies have had mixed findings. They showed that gum doesn’t show any strong positive impact on memory—people who chewed gum didn’t remember lists of words or a story they were told better than others who weren’t chewing. What they did find was chewing gum consistently increased alertness and sustained attention, by around 10 percent.

"If you’re doing a fairly boring task for a long time, chewing seems to be able to help with concentration,” agreed Crystal Haskell-Ramsay, a professor of biological psychology at Northumbria University, who has not been funded by Wrigley. But it depends how alert you were to begin with, she added. If you’re already feeling very awake and focused, it might not add on too much benefit.

There’s also consistent evidence that gum reduces stress, she told me. In an experiment, when people in a lab were asked to give a five-minute public presentation and take a math test, gum reduced their stress levels. In surveys, people who chewed gum were less likely to report being stressed at work. In 2022, women who chewed gum before elective surgery had lower anxiety. But gum may have limits: One study found it didn’t reduce the anxiety of people who were just about to go into an operating room for a C-section. In a group of people who were tasked with solving an unsolvable word puzzle, gum didn’t seem to help them keep their cool either.

Overall, Smith said that gum seems to be able to make you slightly more alert as a short-term side effect.

The best theories for why we like chewing

A more sustaining mystery is how chewing gum could improve attention and reduce stress at all. Researchers haven’t come to any firm conclusions. “How do you go from muscle tension to nerve stimulation to the changes that occur in the brain?” Smith said. “That hasn’t been figured out.” It could be an important mystery to solve: If chewing could relieve stress or improve attention, it would be an easy habit to suggest to those taking tests or feeling anxious, as well as illuminate the connection between bodily movements and the brain.

There are some detailed theories. One is that the act of chewing could lead to more blood flow bringing more nutrients to the brain. Another is that the activation of the facial muscles during chewing could be involved, as muscle tension has been shown to be associated with sustained attention.

Alternatively, chewing might reduce how much a person is paying attention to something stressful out in the world, which influences the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s main stress response system. Attempts to measure cortisol levels of gum chewers, a hormone related to stress, have been mixed too, Haskell-Ramsay said. Sometimes, cortisol has been higher, reflecting higher attention. But chewing could also reduce cortisol at other times, particularly in the morning when cortisol is higher already.

Could the answer lie in evolution? Animals often chew when they’re stressed. It’s possible there’s something primal and comforting about the act of chewing, passed down from our common ancestors with other animals. Adam van Casteren, an evolutionary biomechanic, has studied chewing, but has suggested the opposite: it was human’s ability to chew less that made us the species we are today.

Humans chew much less than non-human primates; chimpanzees chew between four and five hours a day, and gorillas can chew six. Humans chew food, on average, for just 35 minutes. “Before the invention of fire and the use of tools, our ancestors would have also had to have chewed for similar amounts of time,” he said. “It would have been a significant time investment to sit there and chew.”

Gum’s appeal is probably not about an ancestral link to a chewing-heavier era, Van Casteren said. It’s not a vestigial habitat left over from caveman times. His best guess: “Humans just like to do repetitive things,” he said. “I’m a foot shaker when I'm thinking.”

Consider other repetitive motions like tapping your toes, squeezing a stress ball, or clicking a pen. In research on fidgeting, Human Computer Interaction and Games researcher at UC Santa Cruz Katherine Isbister has found that people engage in fidgeting when they’re trying to pay attention to a task that’s taking a long time, or in a long meeting (even if at the annoyance of those around them). Others use fidgeting objects to calm themselves down.

One study from UC Davis let some children with ADHD fidget their bodies as much as they wanted to, and found that those who moved their bodies more did better on a challenging task.

Perhaps gum helps the mind not through a special method, but through fidgeting confined to the mouth. Matthews likened it to walking and thinking. “There’s something to chewing where you can passively process things,” she said. After all, the word ruminate means both to chew, and to think something over.

Despite the gum industry’s current business woes, it’s unlikely gum will ever totally vanish, whether chewed for its mild effects on the mind or not. “From a purely physiological perspective, chewing something without swallowing is pointless,” wrote the novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard. But then he admitted he can’t write without his Juicy Fruit.