Opinion: Nelson Mandela's Prison Release Speaks to Complex Legacy

Mandela's freedom was a beacon of hope, but it could not stop African violence and war.

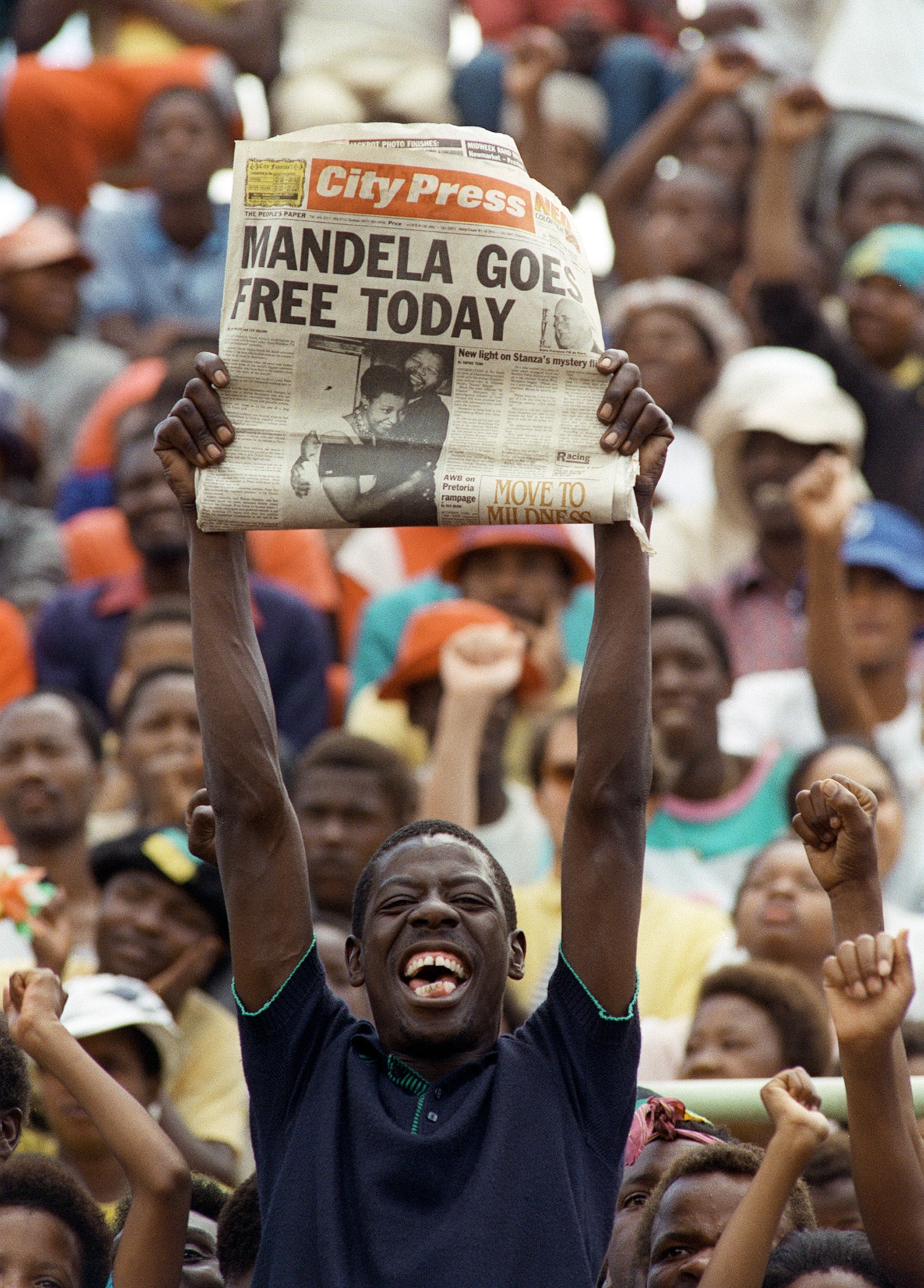

On February 11, 1990, when Nelson Mandela walked out of Victor Verster Prison after 27 years of incarceration, it was a moonshot for the millions of ordinary Africans who had been caught up not only in the fight against South Africa's apartheid regime, but also in ongoing struggles in their own countries.

For them, the release of Mandela—who died Thursday at the age of 95—did not bring an end to violence.

But it was one giant step toward a dream of liberty that had so far eluded not only the majority of South Africans but also millions whose governments had allied as Frontline States against the apartheid regime. (Read "Mandela's Children" in National Geographic magazine.)

To a greater or lesser degree, all the Frontline States countries—Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe—harbored political and military operatives for the African National Congress (ANC), the main opposition to the National Party in South Africa.

Zambia's current high commissioner to London, Lt. Col. Bizwayo Nkunika, who started his career in the Zambia Defense Force in 1972, recalled in a recent interview the attacks undertaken by the South African Defence Force in their pursuit of exiled ANC operatives in his country.

"They carried out daylight air raids on the camps of liberation fighters, killed many Zambians, and destroyed our infrastructure," he said.

In addition, two of the Frontline States countries, Angola and Mozambique, had become caught up in post-liberation struggles of epic and global proportions.

Proxy cold wars of inconceivable horror, the conflicts in those countries were further inflamed by the involvement of the South African Defence Force, determined to fight the threat of rooi/swart gevaar (literally red/black danger—in other words, communism and African nationalism) wherever it washed close to their borders.

During the closing of a speech delivered to a crowd of 50,000 in Cape Town on the day of his release, Mandela repeated what he had said as part of his defense statement during his trial for treason in 1964.

"I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for, and to see realized. But my Lord, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die."

Of all people, southern Africans knew these were the words of a true warrior. After all, in 1961, Mandela had been cofounder of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the ANC.

Southern Africans knew from bitter experience that Mandela's path to freedom had not been a bloodless one. They were also too well aware that blood begets blood. South Africa's fight had never been a neat one, and it had spread far beyond its borders.

War-Torn Countries

From 1964, the year of Mandela's incarceration, to 1989, the year before his release, the South African Defence Force had fought ferociously in a conflict known as the South African Border War, or Grensoolog.

As wars are wont to do, the conflict got messy and entrenched. It spilled out of its Angola/South-West Africa/Mozambique theaters, washed back into South Africa as a civil conflict, and leaked as far north as Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Zambia.

It's believed that as many as a million people died during Angola's civil war from 1975 to 2002.

As many are estimated to have died in Mozambique's civil war from 1977 to 1992.

Anyone tempted to jump on the raft of uncomplicated good versus unequivocal evil would do well to acquaint themselves, just for a start, with the transcripts of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a court-like, restorative-justice body that heard testimony from April 1996 to June 1998.

Unspeakable and, in some cases, as yet unspoken atrocities were committed by both sides in all the theaters of the South African Border War.

It was into this bloodbath of ongoing and immense consequence that Mandela walked on the day of his release.

Complicated Legacy

For many southern Africans then, the ensuing characterization of Mandela by the Western media as an affable saint was not only baffling but also a massive oversimplification.

Whatever else Mandela's release portended, it was already too late to say it was a precursor to a peaceful transition to majority rule, and too late to say that war had been averted.

Mandela's subsequent advocacy for peace and tolerance, his robust and radical vision of forgiveness, didn't end the wars in Angola and Mozambique, and it didn't solve the ingrained habit of violence in his own country.

By some estimates, as many as 200,000 blacks have been murdered in South Africa since 1994. In the same period, more than 4,000 white commercial farmers and some 68,000 urban whites have been murdered.

But it could never have been the task of one man, even a radical catalyst for change, to undo the violence of decades. Like all true warriors, Mandela abhorred war. He fought only when there was no other choice.

In peace, Mandela was the light that cast the rest of sub-Saharan Africa's poor leadership and ongoing injustice into even deeper darkness.

After all, war is Africa's perpetual ripe fruit. There are so many injustices to resolve, such revenge in the blood of the people, such crippling corruption of power, such unseemly scramble for the natural resources.

But Mandela embodied the necessary spirit of forgiveness and leadership that has eluded so much of the rest of the continent.

Editor's note: Alexandra Fuller, a regular contributor to National Geographic, grew up in southern Africa. Her memoir Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight covers her early experiences.