Nepal Slashes Everest Fees; Will Lower Costs Increase Crowds of Climbers?

Will the new fee structure increase the traffic—and the danger—on the busy mountain?

News that the Nepalese government is lowering the fee for climbing Mount Everest has set the mountaineering world abuzz. Last week, Nepal's Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation announced that it would cut the fee it charges during the spring season from $25,000 to $11,000 per climber.

Though still not cheap, the new fee structure would appear to make an Everest expedition somewhat more affordable and thereby available to more climbers. But veteran Himalayan guides say a closer look at the numbers tells a different story and raises old questions about safety and the economic health of the area surrounding the world's tallest mountain.

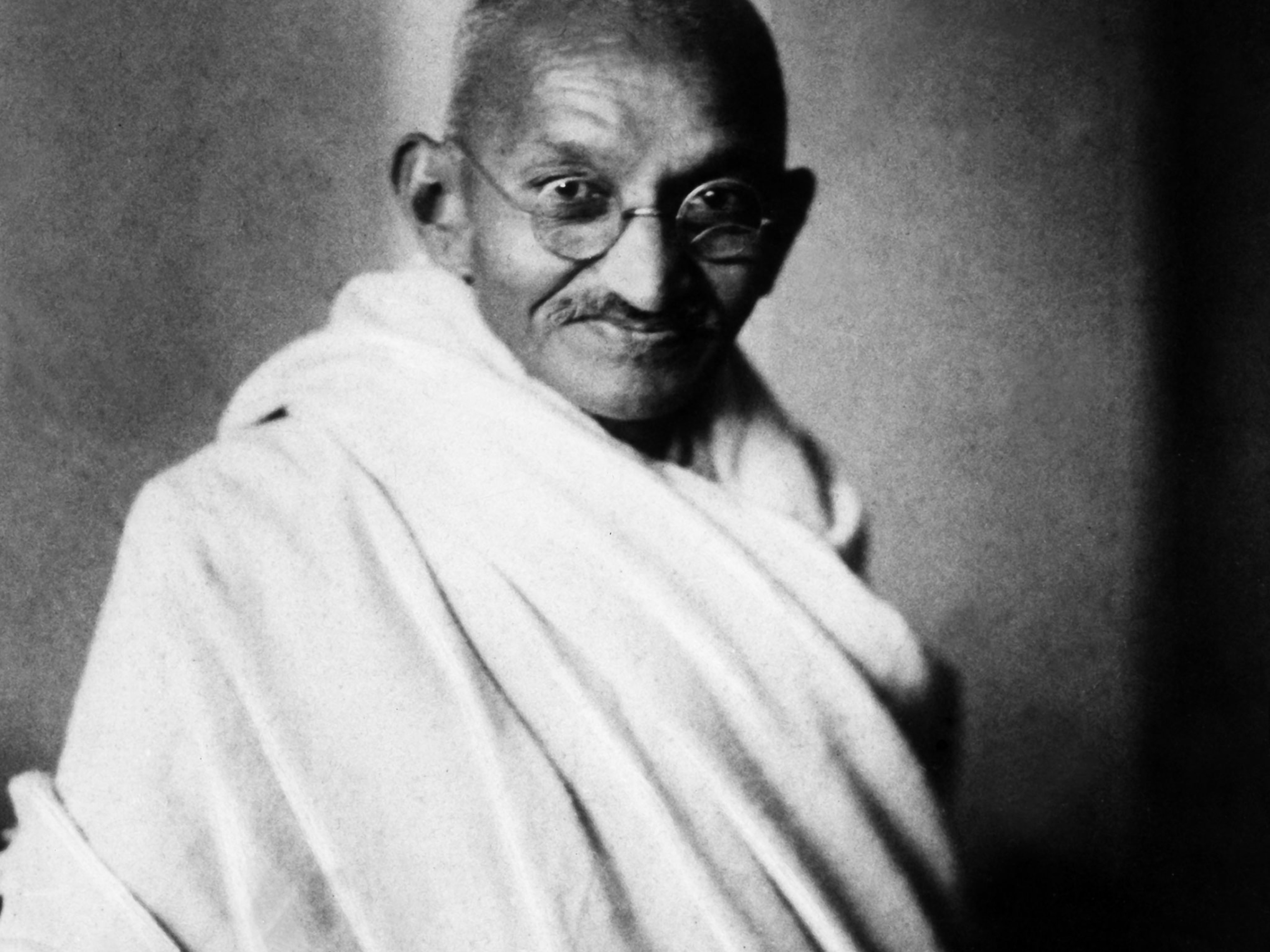

Since New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tensing Norgay stood atop Mount Everest's 29,035-foot (8,850-meter) peak in 1953, more than 4,000 people have followed. Many have paid upwards of $50,000 for the privilege. Ever since commercial guiding became popular on Everest during the 1990s, purists have complained that only the very rich can afford to scale the mountain.

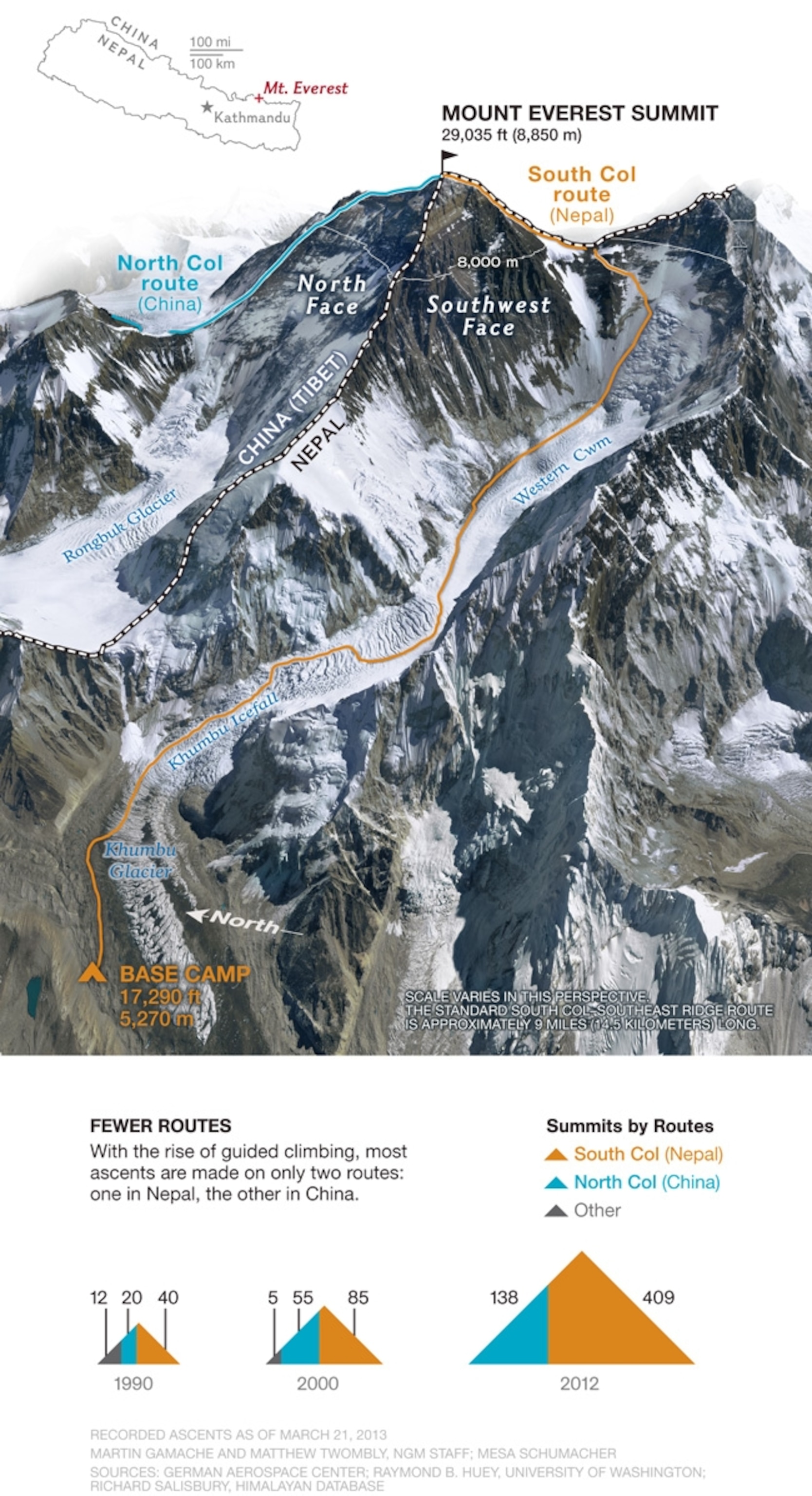

Although there are numerous established climbing routes on Everest, which straddles the Nepal-China (Tibet) border, two routes see 99 percent of the traffic. The North Col route, which originates on the Tibetan side, is regulated by the Chinese government. It costs about one-third the Nepal price but requires more technical climbing near the summit and is attempted by far fewer climbers than the Southeast Ridge route, which rises from the Nepalese side.

In the past, Nepalese government fees for climbing via the Southeast Ridge during the spring were based on a sliding scale, with the cost per climber dropping to $10,000 per person once a team had seven members or more (up to the maximum of 15). Very few climbers paid the full $25,000 price tag. Instead, small climbing teams would bind together under the umbrella of one government permit. Beginning in 2015, when the new fees take effect, the Nepalese price for foreign climbers in groups on Everest will actually increase from $10,000 to $11,000.

Speaking to Reuters on Monday, Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation spokesperson Tilakram Pandey said, "The change in royalty rates will discourage artificially formed groups, where the leader does not even know some of the members of the team. It will promote responsible and serious climbers."

Critics Say Could Add to Crowding

Yes and no, say veterans of the Nepal climbing scene. For experienced alpinists who want to climb Everest as a part of a small, well-acquainted team, the change keeps costs down, although all teams—no matter their size—will still be required to hire a government liaison officer for $2,500 and pay $500 to $600 per climber for the "ice doctors," specially trained Sherpas who install the ladders and fixed lines up through the treacherous Khumbu Icefall.

However, critics of the plan say the pricing structure might encourage less experienced climbers to form small teams as well and could add to further crowding on the mountain. "If it increases the number of camps at Base Camp, subsequently increasing the need for services, from rescue helicopters to support staff, the overall impact to the upper Khumbu region will be negative," says Conrad Anker, who has summited Everest three times and co-founded the Khumbu Climbing Center, which trains Sherpas in technical mountaineering skills and safety. "Every place on Earth has a carrying capacity, and Everest is already over its limit."

To increase the mountain's carrying capacity would require significant investment in infrastructure and government services. Although the Nepalese government collects more than $3 million in Everest climbing fees every year, little of this cash returns to the region for conservation, regulation, or resource management.

"This increase in price will have little effect on the commercial guiding operations on Everest," says Russell Brice, owner and operator of Himalayan Experience, which has put more clients on the summit than any other guide service. "Frankly, an increase of $1,000 is overdue, given that inflation in Nepal is running at 17 percent. Of course, we wish that this money would go back to the Khumbu, but it won't. The government is simply too corrupt."

While one intended effect of the new climbing fees is to reduce the number of climbers on Everest during the popular spring season by significantly reducing the fees for climbing in the less popular fall and summer seasons, Brice is skeptical this will make any difference.

"The chances of summiting Everest in the fall, with deep snow, colder temperatures, and shorter days, is significantly less than in the spring," he says. "Climbing in the summer or winter is even worse. No one will want to decrease their chances of success."

Other Measures, Other Peaks

Brice does commend other measures that the Nepalese government is implementing this year. In the past, the government liaison officers typically made perfunctory appearances at Base Camp to check in with their assigned teams before returning to their offices in the lowlands. This spring, nine liaison officers will be stationed at Base Camp, presumably to help monitor waste management, garbage collection, and traffic along the route—vexing issues that Everest watchers complain have long been ignored by the government. Brice and Anker are hopeful that this contingent could form the basis of a ranger system, something they and other veteran climbers have long called for.

Lost in the discussion of Everest is the news that the revised pricing structure also will reduce climbing fees for other mountains in Nepal—which in addition to Everest is home to seven other 26,000-foot (8,000-meter) peaks. Furthermore, mountains that were previously off-limits now will be open to climbing. In an ever-shrinking world, this comes as welcome news for those who long for unexplored valleys and unconquered summits.

Mark Jenkins summited Mount Everest in 2012. His account of the expedition, "Maxed Out on Everest," appeared in the June 2013 issue of National Geographic magazine.