Syrians Race to Save Ancient City's Treasures from ISIS

As ISIS fighters invaded Palmyra, museum curators were packing artifacts and loading trucks for a last-minute escape.

Syria’s Director General for Antiquities and Museums got a telephone call in mid May that he had long been dreading: Thousands of ISIS fighters were racing across the desert toward the 4,000-year-old oasis city of Palmyra.

The director, Maamoun Abdulkarim, knew it was up to him and his staff to save Palmyra’s antiquities from destruction. Cultural heritage groups had tried in vain to persuade the U.S.-led coalition to conduct air strikes on the invaders as they stormed towards Palmyra’s magnificent ruins, which are designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

But in contrast to other battles in Syria and Iraq, where warplanes carried out hundreds of precision bombing runs, there was only a single airstrike on Palmyra, which knocked out an ISIS missile and artillery battery but failed to stop their siege.

(Read about why ISIS hates archeology.)

Without help from the air, there was nothing Abdulkarim could do to protect the vast archeological site itself, with its rows of stone columns, Roman amphitheater, ornate tombs, and myriad temples. But he and his men could try to rescue the trove of artifacts inside Palmyra’s museum.

Roads Full of Bandits and Rebels

Appointed to his post in 2012 by the Syrian regime, Abdulkarim orchestrated the operation from Damascus. Meanwhile, museum staff in Palmyra barricaded themselves inside the imposing building and began wrapping and crating Greco-Roman statuary, jewelry, ancient glass, and mosaics.

After six days of fighting the tide turned decisively against the Syrian forces. The jihadists were on the verge of conquering Palmyra, and it was Abdulkarim’s last chance to spirit away the museum’s treasures.

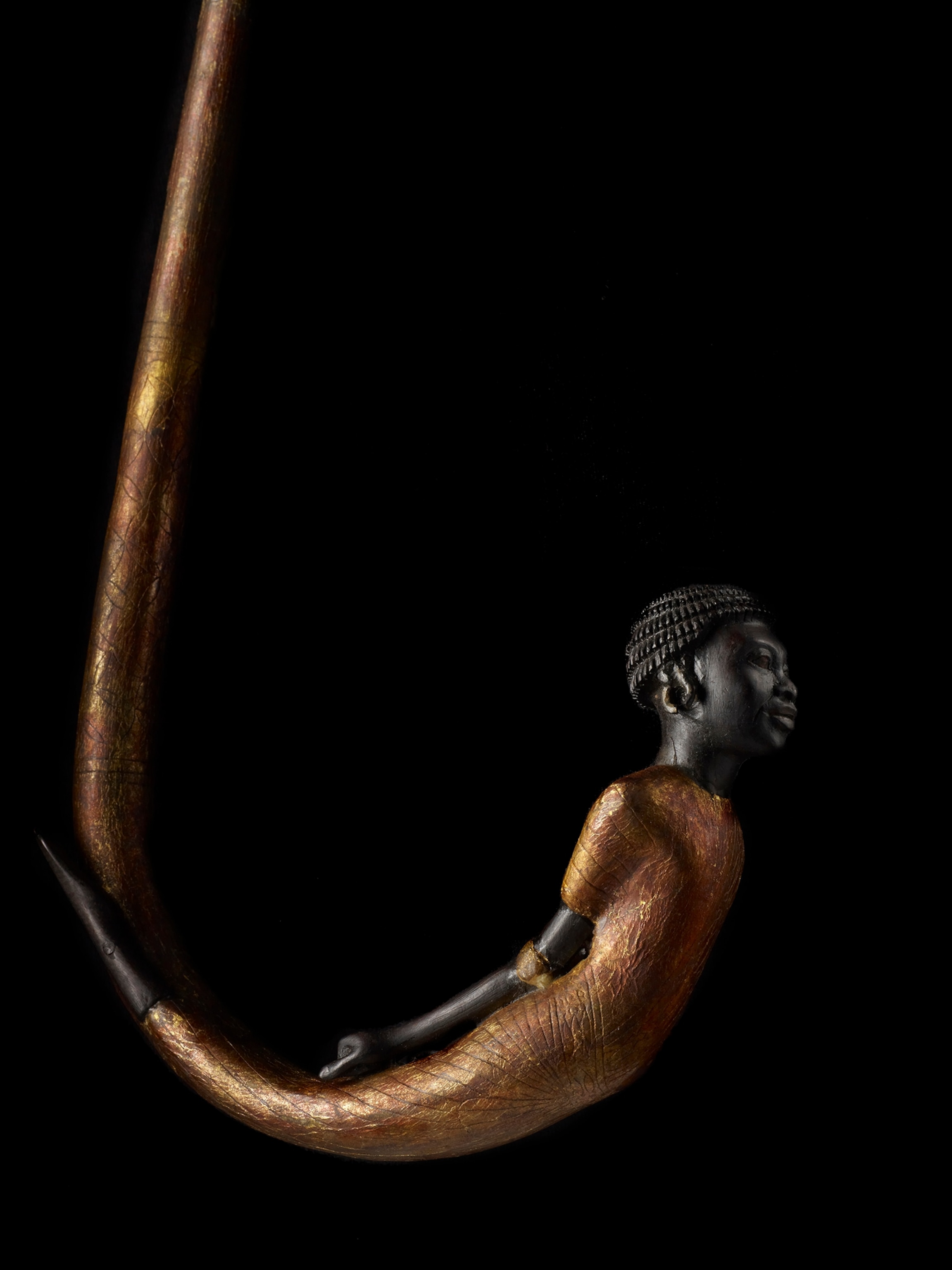

The museum’s prized mummies were hidden inside bricked-up enclosures. A stone lion nearly 2,000 years old and weighing 1.5 tons was too heavy to be moved, so the staff encased the lion inside a large metal box.

(Learn about the many archeological sites ISIS has attacked.)

In Syria’s brutal, four-year civil war, rebel forces—ranging from secularists to rival Islamic militias—are fighting to destroy the Damascus regime, as well as each other. Over 230,000 Syrians have died and, according to the United Nations, over 300 monumental sites have been plundered, damaged, or destroyed.

The battle for Palmyra seesawed back and forth for nearly a week. ISIS fighters shelled the town from an ancient hilltop castle, but the Syrian army drove them out. Meanwhile, Abdulkarim tried to secure military aircraft to airlift the museum artifacts.

It proved impossible. There were no longer any flights, he was told; ISIS fighters had overrun the airport. Then the jihadists seized another prize—the gas fields outside Palmyra.

Syrian generals rushed in a few hundred troops—all they could spare from battles elsewhere—but ISIS brought in nearly 800 fresh fighters, including hardened veterans from Afghanistan and Chechnya. The Syrian troops were outnumbered and outgunned.

After six days of fighting the tide turned decisively against the Syrian forces. The jihadists were on the verge of conquering Palmyra, and it was Abdulkarim’s last chance to spirit away the museum’s treasures.

“We didn’t want to use the road to move the artifacts. It was full of bandits and rebels,” says Abdulkarim. “But finally we had no choice.” Two trucks were hired.

Last Defenses Crumble

Early on the morning of May 21, as the trucks pulled up outside the museum and the staff rushed to load the crated artifacts, the Syrian army’s last defenses crumbled. Witnesses said that Syrian officers fled, leaving their conscripts at the mercy of ISIS fighters. Many soldiers fled into town, banging on doors and pleading to be let inside. Many were caught and killed. Like in many other towns in Iraq and Syria that fell to ISIS, the jihadists marked their triumph with scores of public beheadings.

ISIS fighters overran the ancient ruins. They swarmed up a long, colonnaded boulevard, where more than a thousand years before Roman legionnaires had once paraded, merchants rode in on camels laden with finery from India and Persia, and a rebel queen, Zenobia, was led away in gold chains.

ISIS fighters have placed explosives all around the archaeological site and now are poised to destroy the ancient columns and temples if the Syrian army tries to drive them out.

Nearing the museum, the jihadists spotted the curators moving the crates into the trucks and opened fire. Three employees fell, wounded and bleeding. Their colleagues dragged the injured men into the trucks and sped out of the museum grounds just as the jihadists closed in, firing round after round at the fleeing vehicles. “Seconds longer, I don’t know what would have happened,” says Abdulkarim.

(Read about looted antiquities returning to Iraq despite threats from ISIS.)

The curators dropped off their wounded colleagues at the hospital in Homs, the nearest city, and continued on to Damascus. There, according to Abdulkarim, the antiquities were stashed in secure locations. “We managed to save 95 percent of the museum’s artifacts,” he says.

Artifacts’ Fate Unclear

That figure may be overly optimistic. Michael Danti, Academic Director of ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives, says that a number of significant objects went missing even while Palmyra was under Syrian military control. “It’s hard to tell what was taken before the Islamic State, what was stolen, and by whom,” he says.

Antiquities trackers from the Heritage for Peace say that a number of Greco-Roman busts, jewelry, and other objects from the Palmyra museum found their way onto the international market. Police and customs officers in Turkey and Lebanon confiscated numerous antiquities after receiving tip-offs from its agents scouring bazaars in Beirut, Istanbul, and Gaziantep in southeastern Turkey.

(Read "ISIS Destruction of Ancient Sites Hits Mostly Muslim Targets.")

Recently, photographs circulated on the Internet showing ISIS fighters publicly whipping an antiquities smuggler. Most likely, say archaeologists, the jihadists weren’t exhibiting any newfound appreciation for Palmyra’s heritage. Instead, they punished the looter because he had been caught trying to smuggle antiquities without paying the customary cut to ISIS.

In any case, the militants destroyed the looter’s objects—two exquisite Roman statues—with sledgehammers.

Several days into the occupation, jihadists blew up two historic Islamic shrines built by Shia and Sunni worshippers whose Islamic beliefs are considered heresy by ISIS. Then they pried open the metal protective box around the 2,000-year-old stone lion and blew it up.

According to Abdulkarim, ISIS fighters have placed explosives all around the archaeological site and now are poised to destroy the ancient columns and temples if the Syrian army tries to drive them out.

(A Syrian military aircraft also dropped a barrel bomb on the site, knocking down a wall of the 2,000-year-old Temple Bel-Shamin, even though ISIS fighters were nowhere near the temple.)

Meanwhile, ISIS is making use of Palmyra’s archeological marvels for its own macabre spectacles. Militants recently herded townspeople out to the giant Roman amphitheater to witness an ISIS firing squad execute 26 captured soldiers on the stage where ancient Greek and Roman dramas were once performed.

“A friend of mine was forced to watch,” says Abdulkarim. “He was struck by how the executioners were all teens. They didn’t look older than 13 or 14.”

Tim McGirk, a former Time Magazine bureau chief, is currently managing editor of the Investigative Reporting Program at U.C. Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism.