The greatest library in the world was built by this ruthless king

The 1850 discovery of King Ashurbanipal's vast library of cuneiform tablets at Nineveh illuminated fascinating records and complex links with neighbors.

Ashurbanipal, the most powerful king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the mid-seventh century B.C., was known for his ruthless military prowess, his incredible lion-hunting skills—and for being a librarian.

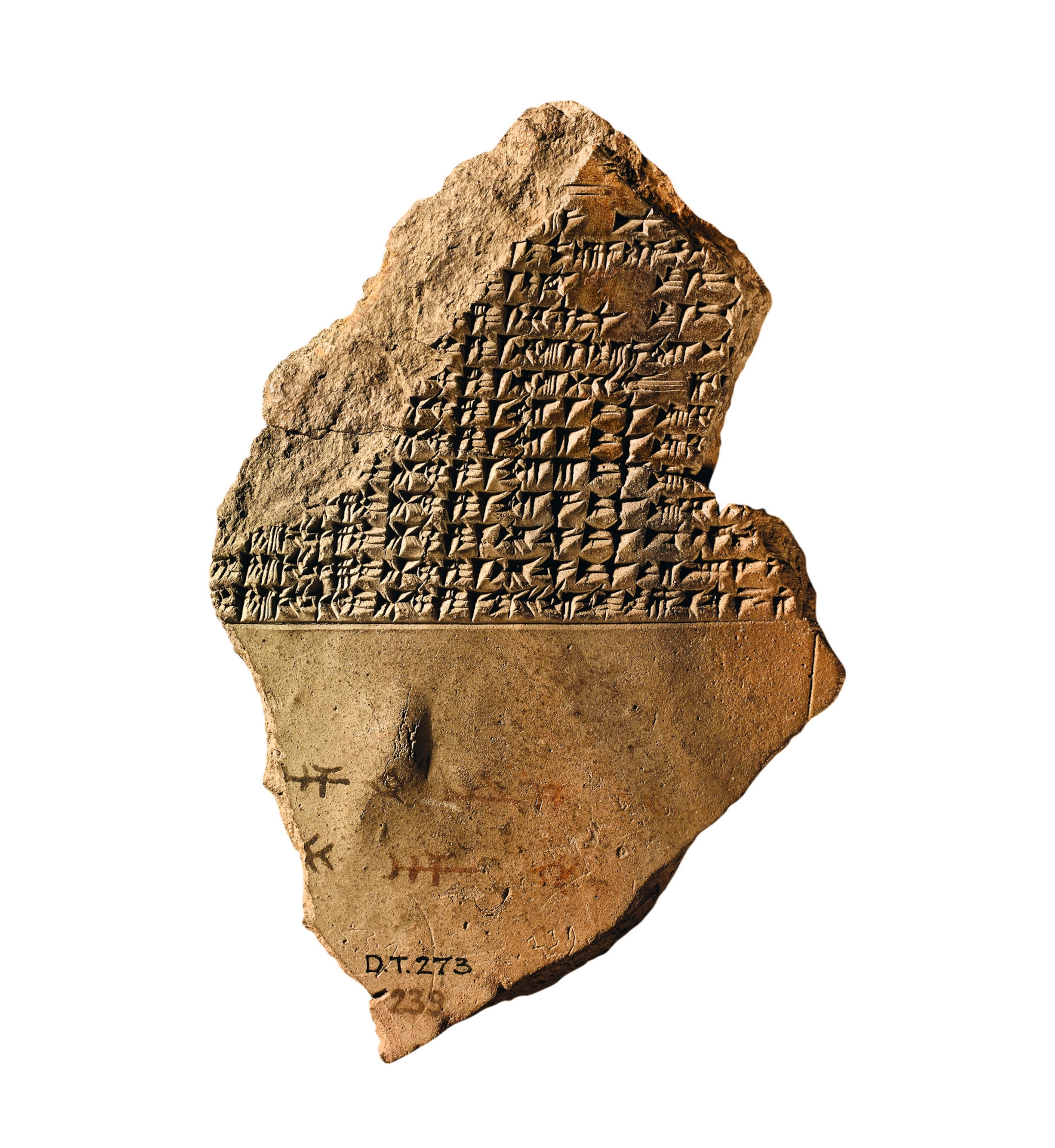

“Palace of Ashurbanipal, King of the Universe, King of Assyria” reads an inscription denoting his ownership on one of over 30,000 clay tablets and fragments from the magnificent library he maintained at his capital, Nineveh, today in northern Iraq.

The 19th-century discovery of the library by British archaeologists was a game changer for Assyrian studies. Previously, documented sources on Ashurbanipal consisted of one reference in the Bible and often fanciful accounts of his life in later classical texts.

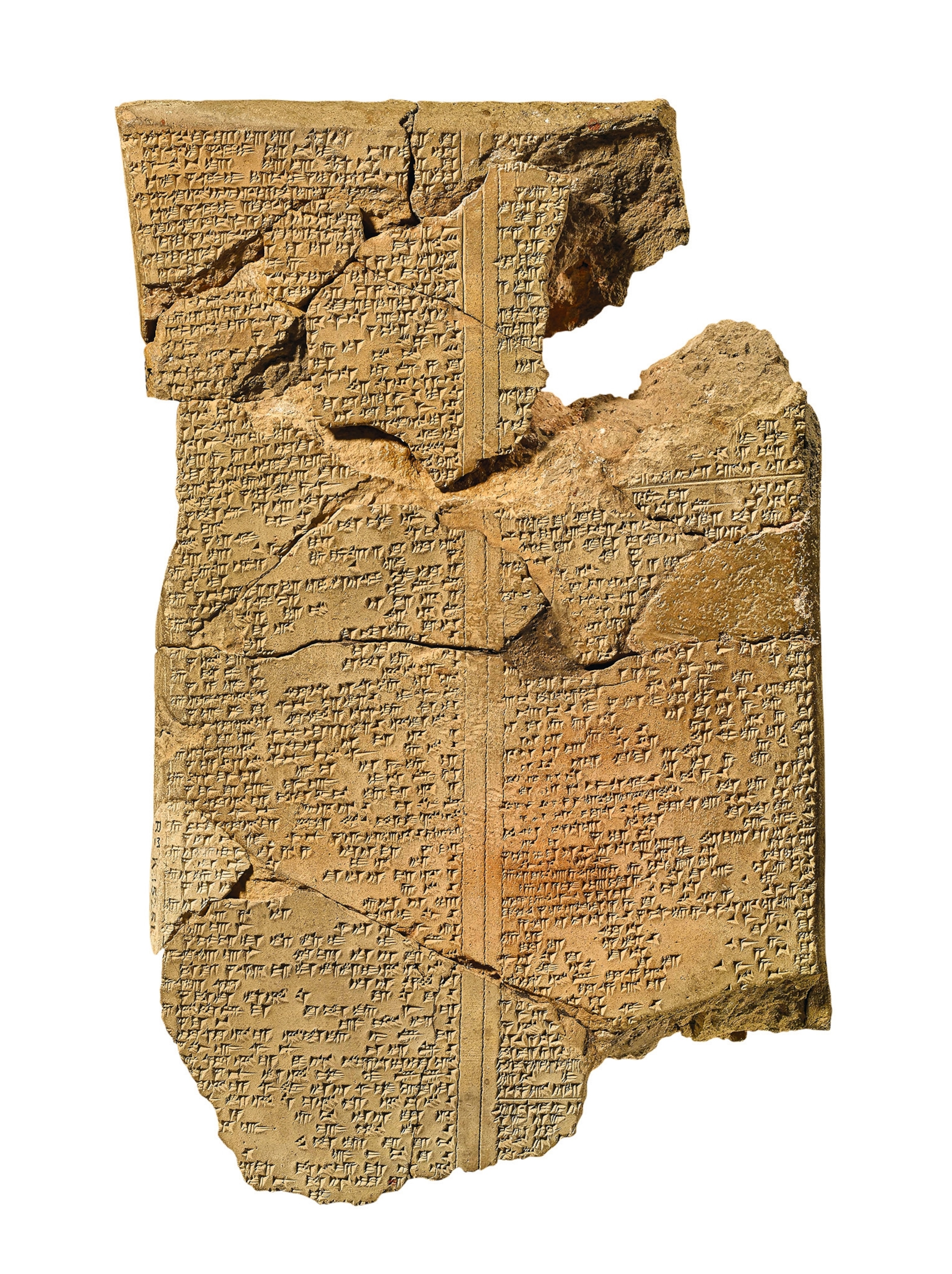

With the discovery of the tablets—on which scribes had used reeds to impress cuneiform (wedge-shaped) letters—the beliefs, liturgy, medicine, politics, and diplomacy of the Assyrian world came into sharp focus. Among the many tablets brought to London was a fragment of the earliest long-form literary work ever found: the Epic of Gilgamesh. Containing stories such as that of the Great Flood, also found in the Bible, the epic electrified 19th-century scholarship.

Seeking Nineveh

Nineteenth-century British scholars had a fascination with the region of Mesopotamia, inspired by their interest in cities named in the Bible. Among these is Nineveh, which the Book of Jonah depicts as a wicked place.

Since the abandonment of the site of Nineveh in the early Islamic period, European scholars knew more or less where it was situated, and references to it appear in the written record. In 1820, British diplomat and antiquarian Claudius James Rich carried out the first formal survey of Nineveh, then under Ottoman rule, where he discovered a relief and some tablets with cuneiform writing. The first large-scale excavations were conducted by British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, between 1847 and 1851. Layard had gained a love for Mesopotamian history during a trip through Anatolia and Syria in the early 1840s. His work at Nineveh unearthed the remains of magnificent palaces adorned with bas-reliefs depicting hunting, war, and banquets. They were built by the two greatest Neo-Assyrian kings, Sennacherib (r 705-681 B.C.) and his grandson Ashurbanipal.

(Why this ancient 'King of the World' was so proud of his library)

Rooms filled with shattered tablets

“The chambers I am describing appear to have been a depository in the palace of Nineveh for such documents. To the height of a foot or more from the floor they were entirely filled with them; some entire, but the greater part broken into many fragments, probably by the falling in of the upper part of the building. They were of different sizes; the largest tablets were flat ... the smaller were slightly convex ... The cuneiform characters on most of them were singularly sharp and well defined, but so minute in some instances as to be almost illegible without a magnifying glass.”

Ancient libraries

In the spring of 1850, Layard’s team found a vast number of tablets with cuneiform writing in Rooms 40 and 41 of Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace in Nineveh. Three years later, Iraqi archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam, Layard’s successor, found a similar storeroom of tablets in the North Palace, built by Ashurbanipal.

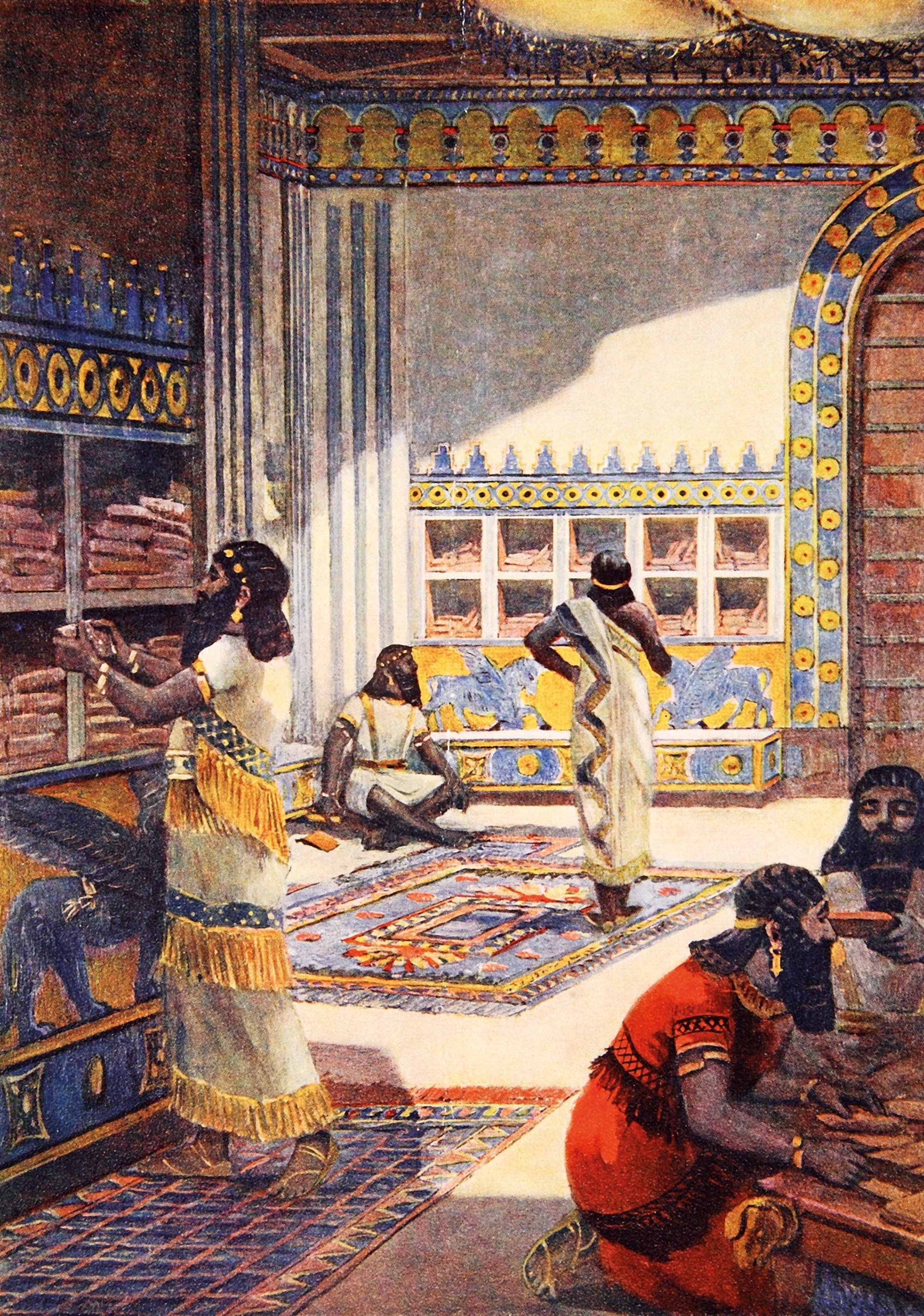

A picture began to form of Nineveh as an emerging cultural powerhouse under Ashurbanipal: In the mid-seventh century B.C., the king sought to make his capital a center of learning to rival Babylon to the south. During his campaigns against Babylon, which had become restive under Assyrian control, Ashurbanipal’s forces plundered vast numbers of scholarly tablets that were then brought to Nineveh. Babylonian scribes were also taken captive and forced to work in the royal libraries. These tactics significantly enriched Nineveh’s collections, filling Ashurbanipal’s archive with centuries of Mesopotamian knowledge, and cementing its status as the intellectual heart of the Assyrian Empire.

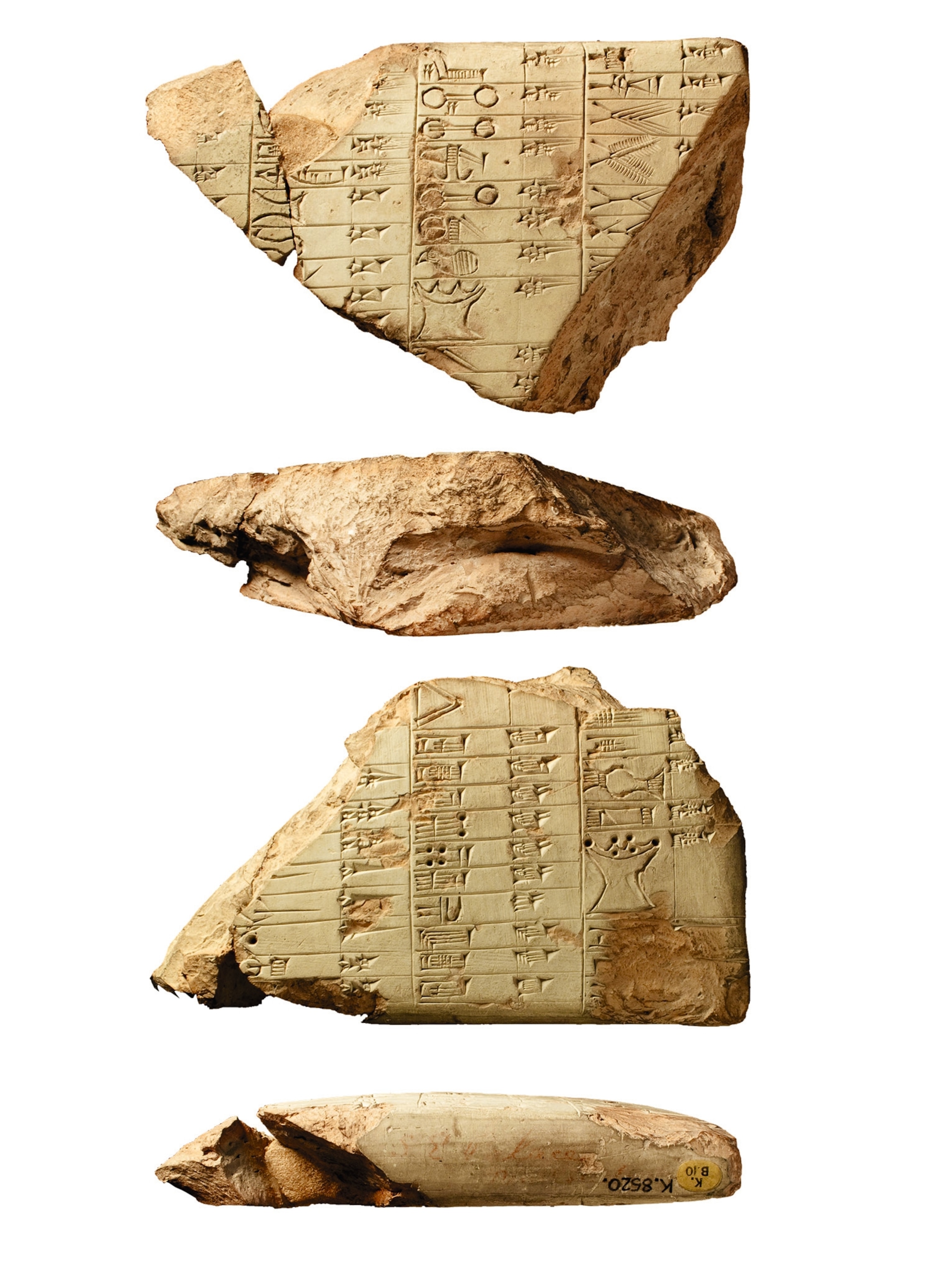

The Assyrians had a word for what we call libraries: girginakku. Used sporadically from the seventh to the second century B.C., the Akkadian word refers to a room, usually in a temple, where scholarly tablets were kept. It also refers to the contents of the collection, which were mainly literary, scholarly, lexical, mathematical, medical, and divinatory.

The stamp of individuality

The main users of the girginakku were the ummânu or “wise men,” scribes who specialized in magic and divination, such as celestial observation, divination using animal entrails or haruspicy, healing through exorcism, or herbalism.

There may have been as many as four libraries in Nineveh: one in each palace and two more in the nearby temples of Nabu (god of wisdom) and Ishtar (the great goddess of love and war). In addition to the libraries, the citadel housed a separate archive for legal and administrative records. These were also severely damaged after Assyria’s fall, but some were recovered and housed in the British Museum. In 2016 the Temple of Nabu and remaining on-site artifacts were destroyed by ISIS.

Many of the tablets found at Nineveh contain colophons (information at the end of the text) stating that they were written or collected in the name of Ashurbanipal. Based on Layard’s findings, in 1901 Cambridge scholar John Willis Clark proposed a layout of Ashurbanipal’s collection, suggesting it had aspects of what would be recognizable as a library, noting, “The tablets have been sorted under the following heads: History; Law; Science; Magic; Dogma; Legends.” Layard’s research strongly suggests a functionary was in charge of the collection, and that it had some form of cataloging system.

(DNA from this 3,000-year-old brick tells the story of a king—and cabbages)

Ashurbanipal emphasized his wisdom. The following is from the “School Days Inscription” about his education. It reads almost like a modern-day résumé:

[Marduk], the sage of the gods, granted me a broad mind (and) extensive knowledge as a gift; the god Nabû, the scribe of everything, bestowed on me the precepts of his wisdom as a present; the gods Ninurta (and) Nergal endowed my body with power, virility, (and) unrivalled strength. I learned [the c]raft of the sage Adapa, the secret, hidden (lore),all of the scribal arts. I am able to recognize celestial and terrestrial [om]ens (and) can discuss (them) in an assembly of scholars ... I have read cunningly written text(s) in obscure Sumerian (and) Akkadian that are difficult to interpret.

When Nineveh began to weaken by the late seventh century B.C., Babylon joined forces with neighboring Media to challenge Assyrian rule. In 612 B.C., the coalition set Nineveh on fire, ending the Assyrian Empire.

Epic consequences

Over 30,000 tablets and fragments recovered by Layard, Rassam, and later excavators, are now preserved in London’s British Museum.

Written by Babylonian scribes, they offer invaluable insights into the literary, scientific, and administrative knowledge of the ancient Near East, and stand as a testament to cultural exchange, not only between Assyria and Babylon but also among neighboring peoples, including the Hebrews.

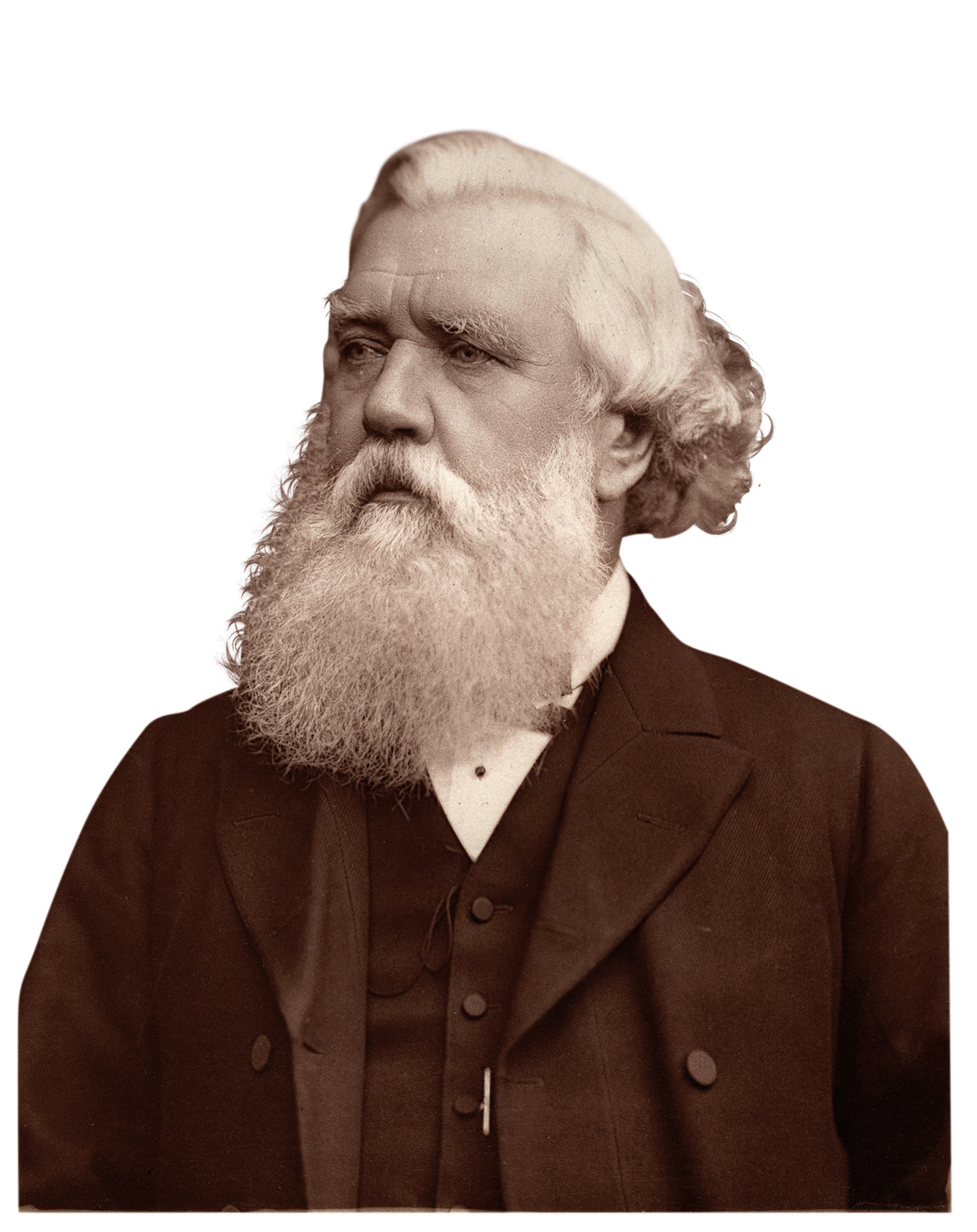

In the 1860s, self-taught Assyriologist George Smith took a job at the British Museum sorting through the large number of Nineveh tablets housed there. One day in 1872, the 32-year-old scholar, surrounded by fragments about itemizing cattle and wine jars, found himself reading a story about a flood, and a bird sent out to search for dry land. The similarities with the story of Noah’s flood in the Bible were so startling that Smith is said to have danced around the room with excitement.

(What really happened to the Library of Alexandria? These are the theories.)

What Smith had discovered was a fragment of the world’s oldest epic poem, centering on the world’s first literary hero: the Epic of Gilgamesh. Spurred to perform marvelous feats, the semidivine king Gilgamesh learns to accept his mortality.

The stories of Gilgamesh developed from Sumerian poems in the late third millennium B.C., and were later woven into a long epic by the Babylonians, whose rich literary culture Ashurbanipal coveted and plundered. The 12-tablet version that came into the library—and which, even then, must have been venerated as an ancient text—is the most complete version of Gilgamesh yet found.

The striking similarity of the Flood story with that of Noah’s ark in the Bible caused a sensation in Victorian England. To some, it affirmed the historical truth of the Bible; to others, it supported the view that the Bible was a cultural reflection of much older Mesopotamian stories. To historians, it demonstrated the rich flow of influences across the region.

Signs, omens, and demons