Every year millions of miracle-seeking pilgrims visit Mexico City

For centuries, devotees have trekked to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe to ask the champion of the disenfranchised for protection.

Andrea Flores Nuñez began to pray in her hospital bed after the birth of her son three years ago. The newborn wasn’t getting enough oxygen, the doctor said, and his lungs were shrinking. They rushed him away to an incubator. In her mind she repeated a promise to the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s beloved patron saint, that she later recalled for her mother: “Mama, I told the virgin that if my son comes out OK I’ll go to the basilica on my knees.”

Every year in mid-December, millions of pilgrims surge up a broad avenue of Mexico City toward the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe for a feast for the Virgin Mary. The anniversary of her apparition to an indigenous Mexican man on a nearby hilltop has been celebrated since 1754. The Virgin of Guadalupe, considered a champion of the underdog and protector of indigenous peoples, has become Mexico’s most ubiquitous symbol. Transcending religion, her image is embedded in patriotism, politics, culture, and everyday life. This year, 20 years since she was named the patroness of the Americas by the Vatican, 9.8 million people from around the world were expected to attend the annual pilgrimage to thank the virgin for their health, families, and miracles delivered the year before.

Three months after Nuñez gave birth, she layered leggings under her pants and left her house in northwestern Mexico City to join the throng of pilgrims. Once through the courtyard gates, she dropped to her knees and crawled toward the basilica to deliver gratitude for her son’s life. Then, her legs covered in scratches, she boarded one of four moving walkways, and was whisked past a sacred cloth imprinted with the virgin’s image. The journey had taken five hours.

On December 12, stories of the virgin’s interventions like Nuñez’s were everywhere: A truck accident that left a nurse nearly unable to walk, but who, after a prayer to the virgin, didn’t need surgery. Sons who overcame addiction. A clogged artery that miraculous cleared. “She was dying,” says Guadalupe Suarez de Jesus, pointing at her mother, Este, who survived heart disease. Guadalupe walked all night from her hometown of Morelos to thank the virgin, as she has for eight years.

The story of the Virgin of Guadalupe begins in 1531, just a few years after Spanish conquistadors seized control of Tenochtitlan, what was then the seat of the Aztec Empire and is now Mexico City. An indigenous man named Juan Diego claimed to be visited by the Virgin Mary speaking in his native tongue of Nahuatl. She asked him to build her a shrine on the hillside, but when the local bishop was told what happened, he didn’t believe it. The virgin appeared again and told Juan Diego to gather roses. When he emptied the roses from his cloak, or tilma, for the bishop, an imprint of her image remained on the fabric. The garment believed to be that tilma now hangs behind the pulpit of the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City.

“She appeared at a time when the native people of Mexico were conquered physically and spiritually,” says Socorro Canstañeda-Liles, author of “Our Lady of Everyday Life: La Virgen de Guadalupe and the Catholic Imagination of Mexican Women in America.” “That’s why she’s so important, particularly to sectors of Mexico who are marginalized…She’s a symbol of dignity and affirmation of a people whose lives and religion are questioned.”

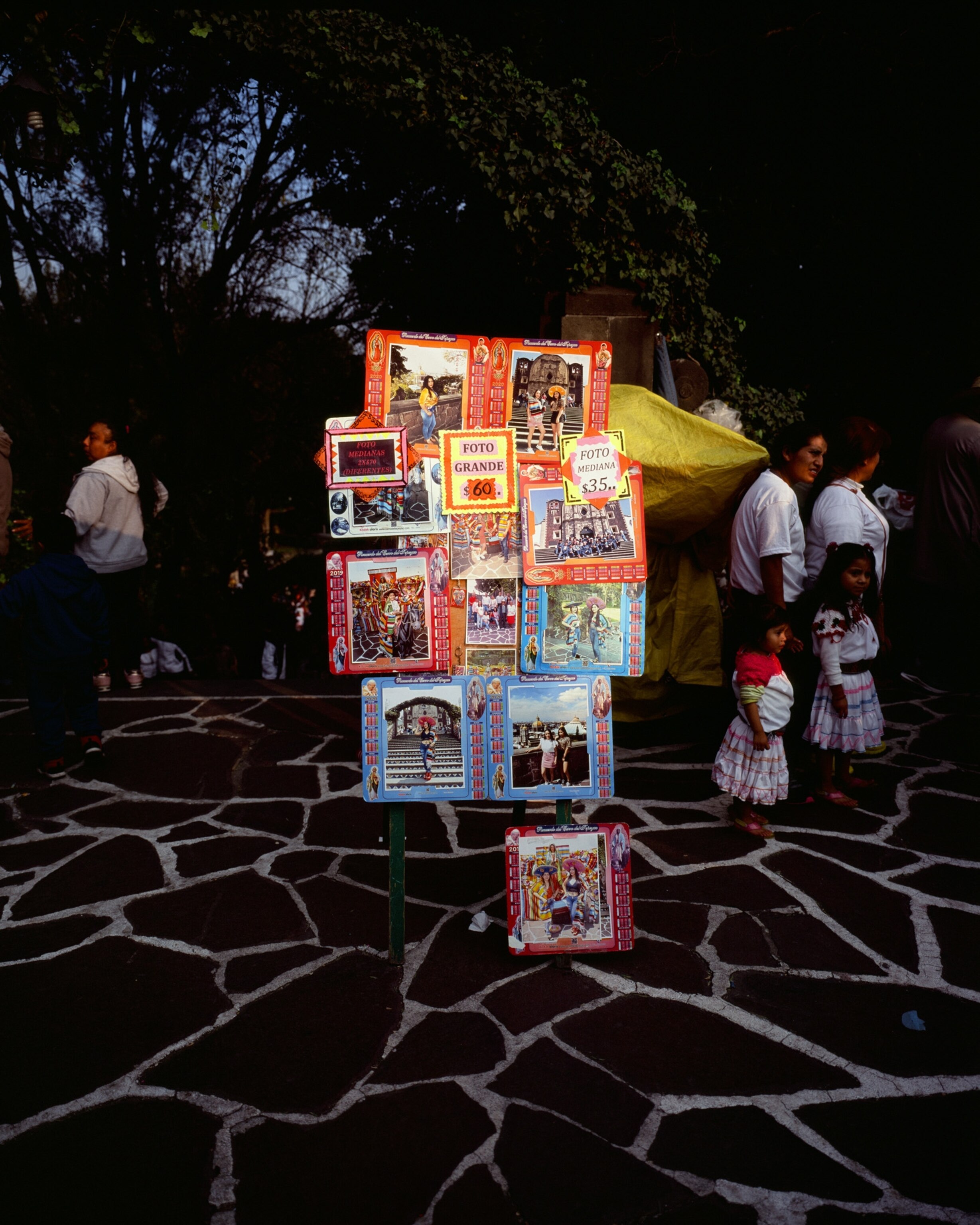

In the days before the December trek, pilgrims from across the country—and the world—arrive to Mexico City. They come in buses draped with religious iconography, pickup trucks hoisting three-dimensional models of the apparition story, and motorcycle taxis covered in lights and balloons. Bicyclists ride in packs followed by support vehicles. A small group of cowboys clomp through the streets on horseback. For 24 hours, traffic is gridlocked and the medians are filled with tents. Inside the basilica, pilgrims hustle onto a moving walkway to catch a glimpse of the virgin’s image.

She is depicted as dark-skinned, dressed in blue, head bent, and hands clasped in prayer. Rays of sun shoot out from behind her. Her image graced banners in the 1810 revolt against the Spanish. She was carried 100 years later as a symbol of patriotism by leader Emiliano Zapata and his troops as they marched into Mexico City during the Mexican Revolution. A decade after that, her image was used by rebels in the Mexican civil war, which eventually overthrew a dictatorship. Today, her image adorns T-shirts, public plazas, and small shrines installed on street corners to watch over passersby.

For centuries, the virgin has been considered a protector of the disenfranchised.

Though her apparition is credited as sparking a wave of conversions and helping the Spanish colonizers in their religious conquest of Mexico, some Aztec traditions may have survived under the guise of the virgin. “[I]ndigenous peoples seemed to fervently practice Catholic religiosity, but they practiced a double religion, keeping their gods and festivities hidden behind new holidays and images,” says anthropologist Renée de la Torre, a professor at Mexico’s Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology.

For instance, the hill where the apparition is said to have appeared had previously been a place for worship of the Aztec goddess known as Tonantzin, and the virgin is still commonly called by that name, meaning Mother Earth in the indigenous language of Nahuatl. Below that site, in the basilica’s courtyard, groups of dancers from across the country perform before and during the feast. Their music, costumes, and moves imitate Aztec styles—all in the worship of a Catholic patroness.

In researching her book, “Our Lady of Everyday Life,” academic Socorro Castañeda-Liles wanted to investigate whether the virgin really served as “a role model of submissiveness,” as previous feminist analysis had concluded. But her interviewees, all first-generation Mexican-American women, told her “a very different story.” In nearly 150 interviews, she heard tales of the virgin helping women break through societal barriers and assert themselves. One woman said that the virgin gave her the strength to shoot her husband when he tried to kill her. “The Guadalupe she knows is not a Guadalupe that says, ‘Endure everything, be all loving and accepting,’” says Castañeda-Liles. “The one she has faith in calls to action, not endurance.”

The celebration of Mexico’s most famous female figure comes after a challenging year for women in the country. The summer was filled with angry protests in the capital. Emergencies were declared in 20 states due to a spike in violence against women. An estimated nine women are killed every day in Mexico, making it the second-most dangerous country for women in Latin America. This year, femicides—women killed because of their gender—increased more than 10 percent. While the pilgrims marched to the basilica in Mexico City, an image circulated on Instagram of the virgin painted with the words “I’m not here anymore…I'm one more of the 9 women that they assassinate in Mexico every day.” The caption read: “Today there is nothing to celebrate in a femicide country.”

The treatment of women in Mexico today is tied to the virgin’s legacy, says Susana Vargas Cervantes, a Mexican researcher who studies gender and sexuality. The ideology of mexicanidad, or what it means to be Mexican, “established who is an ideal Mexican woman versus not ideal,” she says, “and has been terribly influenced by the invention of the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

While writing a book about a killer who targeted elderly women in Juarez in the 1990s, Vargas wondered why police prioritized those cases but largely ignored the hundreds of young women killed and thousands who disappeared. The older women, she deduced, were perceived as the virgin’s embodiment—de-sexualized, maternal, self-sacrificing—while the younger women were seen as the opposite. This had seeped into how law enforcement handled the cases, she believes. “It’s not a matter of faith, it’s a matter of how the image has been used, politically,” says Vargas. “There’s this perception of how a woman should be that permeates an investigation.”

Late at night before the feast, an endless crowd packed along the broad Calzada de Guadalupe leading toward the basilica sang the virgin a traditional happy birthday song called Las Mañanitas. Vendors sold hot drinks, socks, and puffy vests. Every ten minutes a line of people holding back the masses with a thick rope raced to the side and allowed the pilgrimage to surge forward. They wore matching tracksuits, scarves, sweatshirts, and hats while waving flags, and chattered in Spanish, English, Polish, French, and indigenous dialects from across Mexico.

Some carried statues of the virgin on their backs and framed images of loved ones hanging on their chests. A few crawled along the avenue on their knees, flanked by supportive friends and family, a show of gratitude for a miracle granted by the virgin in the past year.

A few miles from the basilica, Andrea Flores Nuñez and her mother, Rocio Olympia Nuñez, stood at a small park next to a busy street. They waited for her brother to bring a box of chicken tamales to feed the weary pilgrims trekking toward the basilica, still two hours away by foot. Along the roadside, clusters of families were doing the same, doling out meals and hot drinks from small tables to an endless stream of pilgrims.

More than a decade before Nuñez made the journey on her knees, Olympia was in front of a hospital altar, promising the virgin she would do the same thing in exchange for healing a hole in her other daughter’s heart. “You have to promise something that’s gonna hurt,” she says, laughing.

“The Virgin of Guadalupe is the mother of all,” says Olympia. “It’s one thing when your parents tell you, but it’s different when you live the miracles with your own flesh.”

Both she and her daughter say they have now seen those miracles for themselves. And they continue to make the journey to the basilica, not just on December 12, but throughout the year. The neighborhood where they live and work is one of the most dangerous in Mexico City, and every day when Andrea’s kids leave for school she asks for their protection. She shows her six-year-old daughter tutorials on YouTube about how to respond if someone tries to grab her, and when she asks to play in the park across the street the answer is always no. After the tamales were gone, around midnight, Andrea headed toward the basilica to thank the Virgin of Guadalupe for providing that protection in previous years and for coming ones.

“She’s a part of us since we were born,” says Andrea. “She’s a part of our Mexican tradition.”