How France invented the restaurant–and started a food revolution

The concept of the modern restaurant emerged in Paris in the 18th century, and its original bourgeois beginnings eventually became shaped by revolutionary upheaval.

French culture is often defined by its fine cuisine—but that wasn't always the case. Until the late 18th century, travelers who wrote about their time in Paris painted a bleak picture of the city, complaining about not only the dimly lit streets but also the poor dining options: “Wealthy people of quality feast deliciously, for they all have their own cooks,” German scholar Joachim Christoph Nemeitz wrote in his 1727 tourist guide Séjour de Paris. Without an invitation to these banquets a typical visitor to the city “does not fare well at all, either because the meat is not properly cooked, or because they serve the same thing every day and rarely offer any variety.”

Dining out in prerevolutionary France offered little excitement. Inns and lodges fed both horses and humans with no particular elegance; hotels provided little more than staples; taverns and cabarets catered mostly to drinkers; rotisseries sold precooked meats to take home; and cafés served only ice cream and liqueurs. The concept of a restaurant as we know it—a place where you can choose from a menu and enjoy a good meal—didn't exist yet.

(Bastille Day celebrates the rebellion that ignited the French Revolution)

The restaurant pioneer

The pot began to stir in 1765, when French entrepreneur Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau served up tiny cups of soup made with broth, salted poultry, and fresh eggs on little marble tables in a former bakery on Rue des Poulies, near the Louvre. Roze was also a philanthropist, and his revolutionary idea—to make good food accessible— was part of his broader egalitarian vision for French society still shackled by Louis XV’s reign.

Dishing up a new word

His notion of offering simple, quality meals at fixed prices and hours was an immediate success, as word traveled quickly among Parisian intellectuals drawn to its convenience and ease. French philosopher Denis Diderot, famous for his radical ideas that revolutionized French society, ate his first meal there in September 1767. He was impressed: “It is wonderful and it seems to me that everyone is praising it.” Diderot also pointed out that “one eats alone” there. Roze had introduced innovative features now seen as standard—individual tables, menus with prices, crockery, and table linens. Above the door, Roze had a sign that read,“Come to me, those whose stomachs ache, and I will restore you,” which was a clever culinary twist on a biblical verse. At the time, doctors were starting to consider digestion key to a healthy lifestyle, and Roze’s simple, easily digestible fare was aligned with this.

Over time, the new eateries came to be called restaurants, and the owners restaurateurs. But Roze had only taken the first step; it wasn’t until 15 years later that the concept really took off—and it did so in a specific area of Paris, in the vibrant arcades of the Palais-Royal. This semi-enclosed complex, once a royal residence, had become a hub of Parisian life—a mix of manicured gardens, theaters, bookshops, gambling halls, and cafés where people from all walks of life mingled. It was here, in 1786, that Antoine Beauvilliers, former chef to the Count of Provence and future king Louis XVIII, opened La Grande Taverne de Londres, the first authentic restaurant in form and spirit.

(Who the world's first celebrity chef?)

Refined taste in newly reimagined Paris

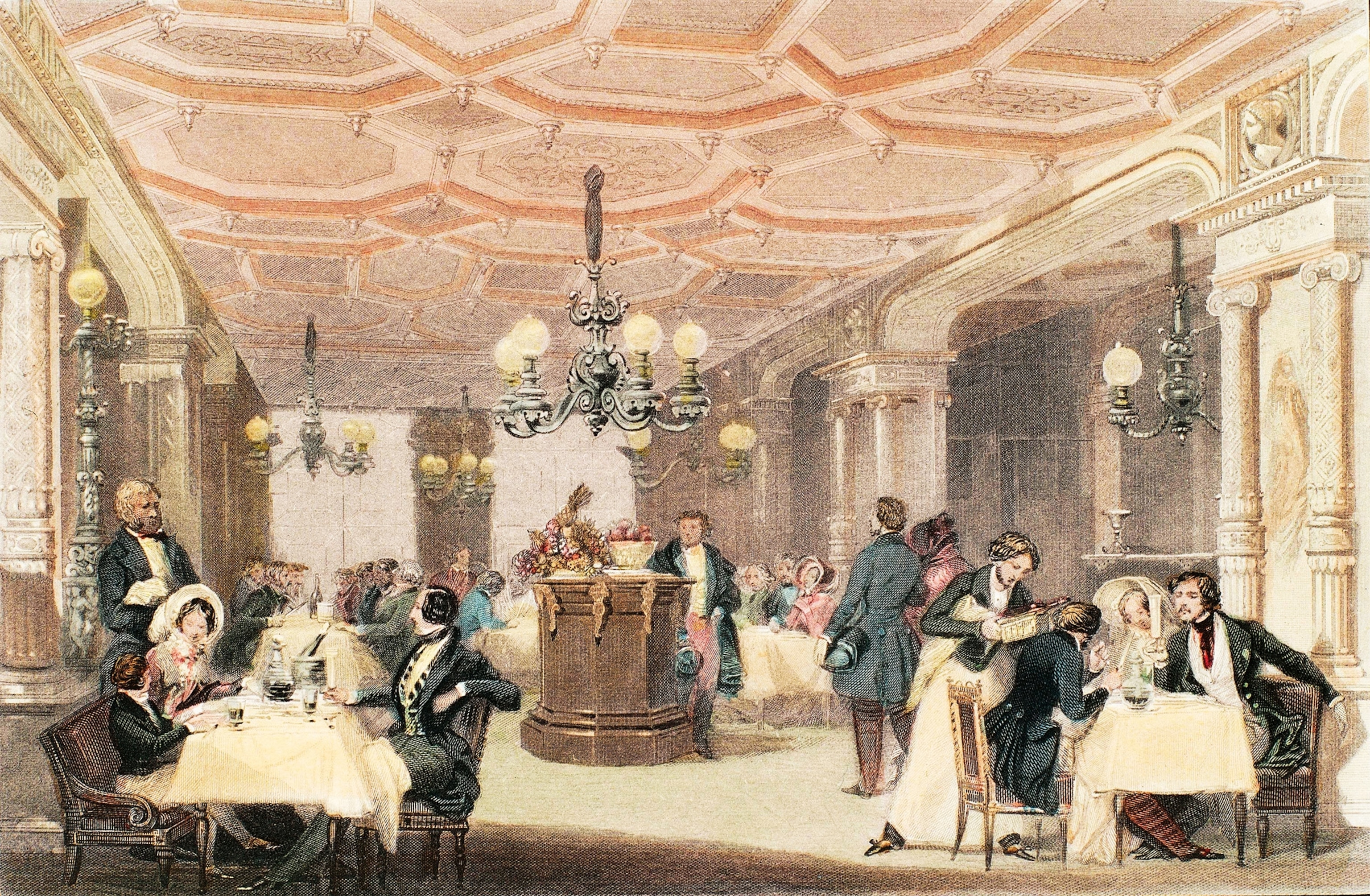

“Upon entering a café or restaurant ... one is captivated by the magnificent mirrors that cover the walls almost to the ceiling, reflecting and multiplying every object in the room to infinity. A pretty porcelain stove usually occupies the center, and several lamps with beveled glass shades hang from the ceiling. Statues, vases, pewterware, and columns adorn the rooms. On one side of the room is a high desk where the deity who presides over the household sits; elegant and beautifully dressed ... she greets you with a graceful bow of her head. She also writes the bills. In all circumstances, she maintains her good humor, her dignity, and perfect self-control.”

Chef Beauvilliers

Beauvilliers took Roze’s egalitarian idea a step further, bringing the aristocratic fine dining experience from the private mansions of the nobility into the public sphere. La Grande Taverne exuded opulence with its polished mahogany tables, richly upholstered walls, and a chandelier that bathed the room in golden light. The lengthy menu was intended to impress the select clientele. An English traveler who visited in 1798 recorded the staggering 178-item menu: 10 soups, 12 starters, 10 beef dishes, 36 desserts, and more. It wasn’t just a meal, it was an event. Beauvilliers transformed each meal into an experience in which diners received personalized advice from the maître d’ and felt like they were part of a shared ritual.

French actor François-Marie Mayeur de Saint Paul captured the atmosphere in his Tableau du Nouveau Palais-Royal (1788), while describing a clientele of “decorated military men, businessmen, distinguished people.”

A revolutionary boost

Behind this polished facade, political tensions were simmering in the Palais-Royal. The quarter had long drawn a colorful cross section of society— attracting the aristocracy and middle classes by day, and libertines and sex workers by night. The same district that celebrated luxury meals and cultivated the art of “seeing and being seen” also became a crucible of dissent, where ideas of liberty and equality spread with gossip and indulgence. When the Revolution unfolded in the spring of 1789, tensions between the elite and the masses erupted into something that would soon become transformative for the City of Lights and beyond. Dramatist Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a keen observer of Parisian life, wryly remarked that “the kitchen’s altars were erected right next to the guillotine.”

The restaurant, born of bourgeois aspirations, was now shaped by revolutionary upheaval. As exiled nobles’ kitchens closed, their displaced chefs flooded the market, launching independent ventures across Paris. By October 1789, thousands of provincial deputies had taken up quarters in the capital to draft a new constitution. They needed calm, orderly spaces to dine and debate, and the city’s restaurants fit the bill.

Conquering the city and beyond

Restaurants spread like wildfire. Up until 1789 there were around 50 restaurants in Paris, but by 1804 there were over 500, in 1825 about a thousand, and in 1834 more than 2,000. Following Beauvilliers’ lead, a new generation of restaurants had sprung up around the Palais-Royal, and fashionable venues like Méot, Véry, and Les Trois Frères Provençaux offered a taste of aristocratic refinement to the rising bourgeoisie.

The focal point for restaurants soon shifted to the boulevards, the great avenues that encircled Paris and were used as promenades. Restaurants were no longer just luxury establishments; they were also available to the lower classes. As early as 1788, Mercier claimed in his famous chronicle Tableau de Paris, which explored life in the French capital, that “a simple workman who earns 200 ecus a day goes to eat at a restaurant; he exchanges cabbage and bacon for poularde and watercress,” one of the most famed dishes of the time.

In 1855, butcher Pierre-Louis Duval opened his first bouillon, an original concept of being affordable to the less fortunate. Customers could now eat on-site, enjoying cuts of meat alongside a vegetable stew—a precursor of fast food.

Competition among chefs in France became fierce, with some deciding to try their luck abroad. French-style venues started emerging in other European cities. New York’s Delmonico’s is often credited as being the first restaurant in the United States, having opened its grand, ornate doors to the public in 1837.