‘Like a dystopian novel’: Puerto Rico still mourns, five years after María

For many Puerto Ricans, “time stood still” after the deadly storm, which was followed by a series of other misfortunes.

San Juan, Puerto Rico — Everyone on this Caribbean island understands that the phrase “en María”—in María—refers not to a place, but to a place in time. Not the sixteen hours Hurricane María spent whipping the island with 155 mph winds, blowing down trees, homes, bridges, electrical lines, cell phone towers, and everything else in its path. And not the 20 inches of rain the tempest poured over the devastation, unleashing landslides and epic flooding.

“En María” refers instead to the long, miserable months Puerto Ricans endured during the aftermath of the worst natural disaster to strike the island in modern history: Weeks of standing in line to enter a supermarket where food, water, and hygiene products were rationed. Hours in another queue to get gas for vehicles or to power generators to survive the second longest blackout ever recorded anywhere in the world. (First place goes to the Philippines, following Typhoon Yolanda in 2013.)

It is when, trying to make a phone call to talk to loved ones or report an emergency meant using that hard-to-get gas to drive to a far-away place where someone had snagged a cell phone signal. It was a time of day-long errands, when the usual 30-minute drive could take three or four hours. A time when people suffering chronic health conditions or needing urgent medical care couldn’t reach a doctor. A time when more than 3,000 people perished because of these challenges—or in the midst of them.

When Puerto Ricans talk about “en María,” they’re talking about the interminable, helpless time that came after September 20, 2017, when María, then a deadly Category 4 hurricane, thundered ashore. That extreme weather event was followed by a series of other blows—earthquakes, political turmoil, the COVID-19 pandemic, and ongoing power outages—making life for many residents a race for survival. Many on this island, a United States territory, are still in mourning, having had precious little time to process the staggering losses. And this week, the island was hit hard again by Hurricane Fiona.

No time for mourning

“These last five years have been almost like a dystopian novel,” says Felisha Román Muñiz, 30, who lost her father José Luis Román Meléndez less than three months after the storm. José Luis had been receiving hospice care at the family’s home in Aguadilla, on the western coast of the island, due to a debilitating, terminal illness.

Felisha and her mother, María Lourdes, say they were lucky. Healthcare providers were able to resume home visits a week after the storm, but keeping critical medical equipment running required almost daily trips to nearby gas stations to fuel a small generator. As José Luis was nearing his final hours, his younger brother in New Jersey managed to get on a flight to see him one last time. He arrived at the family home a few hours too late.

After José Luis died, daily life for Felisha was focused on survival. She had no time for mourning. “In 2018, my grief was silent,” says Felisha. “I just didn’t talk about it, and I felt like everyone on the island was the same, that we didn’t have the time to process.”

For Felisha, work became her coping mechanism. She got a job at a call center in San Juan and spent much of that year focused on paying the bills. Like many others, she kept busy to keep from dwelling on the destruction and daily hardships.

Her mom, meanwhile, found solace at a nearby Pentecostal church, which she now attends every Sunday. She also moved in with her aging parents to help care for them. Earlier this year her mother fell ill and died of complications from diabetes at the age of 79. Her death came on the same day María Lourdes’s late husband would have turned 70.

"At some point I think my defense mechanism was to stop feeling, to become numb."Valeria S. Fernández González

María Lourdes still cries when she thinks of José Luis and her mother, and about how much her life has changed over the past five years. But tears are a necessary part of the grieving process, she says. “There are times when you feel nostalgic, but you have to know this is part of life. Only those who cry can heal.”

Lingering trauma

Psychologist Héctor Javier Rojas González says traumatic experiences can skew our perception of time. “When someone is suffering, it’s like time stands still,” he says. Many of his patients in Naranjito, a mountainous town in the center of the island, are still dealing with the consequences of the hurricane.

“I hear how María was like a curse for many of them,” says Rojas González, “how they can pinpoint that, from that moment on, their family is worse off.”

Rojas González had recently finished graduate school when a group of physicians in San Juan organized a trip to bring aid to Vieques, a tiny island off the east coast of the main island.

“Vieques was one of the places that shocked me the most,” he says. He recalls a single mother who was exhausted after spending many nights without sleep. The windows of her home had to remain open because of the intense heat, and she had been trying to make sure mice that infested the waterless sewer wouldn’t come into her house and bite her baby.

Another resident of Vieques, 65-year-old Modesta Santos Maldonado, had apparent vascular problems and was suffering from a gangrenous toe. The hurricane had heavily damaged the local hospital, and doctors there said they weren’t equipped to help her.

Santos Maldonado’s daughter, Rosa Correa Santos, tried to arrange transport to the main island on an air ambulance, but the aircraft was on its way to a neighboring island. The pilot of a private plane offered to give them a lift to San Juan. That is how they got from Vieques to the steaming hallways of the Centro Médico emergency room.

Three hospitals, death, and cherished memories

Santos Maldonado lay on a stretcher for days with her daughter sitting on the floor next to her. A steady stream of patients kept coming in, many suffering from what looked like life-threatening injuries. A blanket and pillow Correa Santos bought for her at a hospital shop were stolen from her mother’s side.

“They would not say anything,” says Correa Santos. “There were so many people that the only thing we could do was to wait.”

Eventually, Santos Maldonado was moved to another public hospital, but again doctors said they were unable to treat her. She was transferred a third time to a private hospital in the San Juan area. There, on October 1, 2017, she took her final breath. A blood clot killed her just hours before she was scheduled to undergo surgery.

"There were so many people dying,” she says. "They told us that we needed to take my mom out of there or they would have to throw her on the floor, in a hallway."Rosa Correa Santos

Correa Santos quickly arranged for a funeral home to retrieve her mother’s body, afraid it would end up piled up with other corpses in the hospital’s makeshift morgue. That is what she heard was happening from others with similar experiences.

“There were so many people dying,” she says. “They told us that we needed to take my mom out of there or they would have to throw her on the floor, in a hallway.”

Less than three years after burying her mother, Correa Santos lost her 75-year-old father to a stroke. She now lives alone in the family home near a beach she never visits. Inside the house, family photographs remind her of the immensity of her loss. Many are of family gatherings where everyone is smiling.

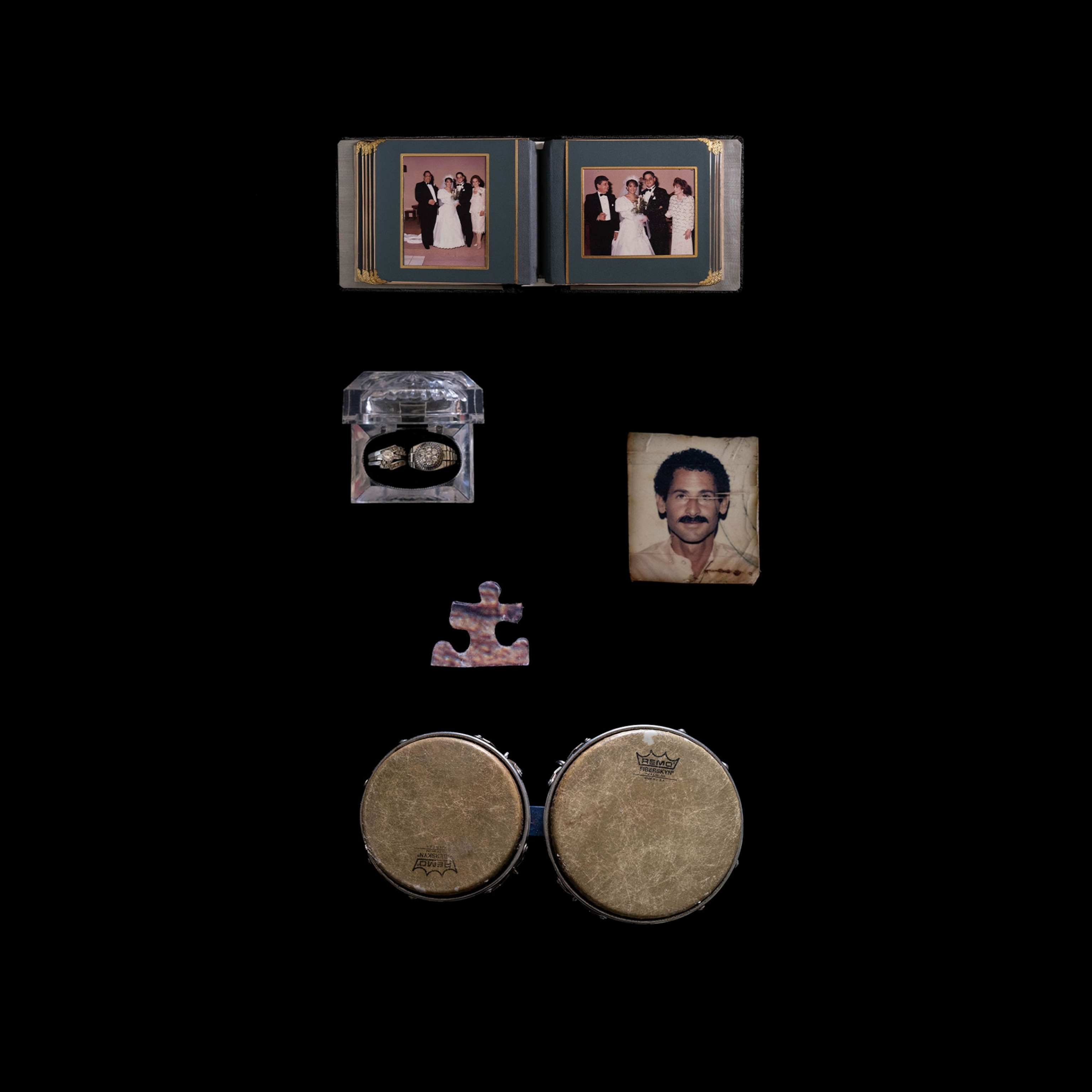

Correa Santos’s most valued treasure is tucked inside a jewelry box hidden in a drawer at the back corner of her bedroom: her parents’ wedding rings. “I was always with my mom and my dad,” she says, struggling to understand how a monster hurricane came one day, was gone by the next, and yet its force is still present.

María keeps roaming the streets of Vieques, where patients who need urgent care—like Santos Maldonado did after the storm—still have no local hospital to receive treatment. María destroyed it. Federal and local governments have failed to rebuild it.

Correa Santos would like to move on, but she finds herself still trapped “en María” each time she remembers the hospital hallways jammed with hurricane victims and the pain and desperation she experienced during those days.

“There’s always something that comes back to you and makes you remember.”

Laura N. Pérez Sánchez writes about corruption and its impacts on the population, post-disaster recovery efforts, and lived experiences under colonialism. She's a 2019 Nieman Fellow, and a contributor to Spanish and English local and international media outlets. Follow her on Twitter.