Outsiders don't venture into this lush corner of India. Could that change?

A rare trek across a remote wilderness finds a village that has declared itself an “ecological zone” in a bid to attract visitors.

AZURAM, MANIPUR, INDIA — Late last summer, I walked for nearly three months through the hills of northeastern India. They shimmered under the sun like the green velvet lining of a jewelry box. They held treasures of vanishing sound.

On the maze of trails outside Khanduli, a village whose market peddled silk worms by the bushel, it was impossible to speak. Why? Cicadas. All the cicadas in the world had converged there. It was the global conclave of cicada-dom. The dripping forests hosted a vast confederacy of cicadas. Their song pulsated through the wet air for mile after mile: a referee’s shrill whistle, blown at full volume, calling a cosmic foul on the apes who imagined themselves rulers of the world. I gestured to my walking companion to approach. I cupped my mouth against his bludgeoned ear. I think we’re lost! I shouted.

In Umrangso, the tree frogs announced their love in the xylophone scales of bamboo wind chimes. I listened to gibbons rocket through the treetops along the Jiri River, dislodging showers of leaves and whooping like soccer hooligans. And everywhere, I overheard the hills speaking the sibilant dialects of unbounded water. The ionic hum of waterfalls. The white hiss of streams. The hard-knuckled rap of monsoon rain on roof tin. Even atop the highest ridges—where I expected nothing but damp wind—came the faint, quavering sigh of wild rivers far below.

This tropical medley harbored exquisite silences: fermata of a kind found almost nowhere else in the inhabited world.

I walked for days in the Jaintia Hills without hearing a machine. No cars. No generators. No irrigation pumps.

Where is the source—the epicenter—of such tenderly silent landscapes?

Is it pooled, like the rain, inside the plate-sized footprints stamped by the last wild bull elephant still haunting the mud path to Rumphum?

FEW OUTSIDERS travel the hills of India’s northeastern frontier.

The region is too remote. Its beauty is without labels. There is “nothing there”: no big national park or other Google-able destination to draw attention.

During my 330-mile walk from Guwahati, the capital of Assam state, through the hinterlands of Meghalaya, and then eastward to Imphal, the lowland capital of Manipur, I saw no foreigners. The Karbi Hills. The Cachar Hills. The Dima Hasao plateau. The hills of Manipur. This rumpled margin of India, close by the Bangladesh border, remains an utterly localized precinct of the world. A cosmos of villages webbed into place by footpaths. A labyrinth of clan territories demarcated by slash-and-burn rice paddies. By storm-gutted roads. By rusting suspension bridges built 80 years ago during British colonial rule.

Throughout history, though, India’s northeast has been a continental crossroads—a “great Indian corridor”—connecting southern China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

Iron Age diasporas of Indo-Aryans and Tibeto-Burmans passed through. The Ahom people walked in from the Kingdom of Pong, in today’s Myanmar, some 800 years ago. When British latecomers showed up in the 19th century to plant tea, they found an established mosaic of more than 200 ferociously warlike and independent indigenous groups. Today, these ethnic minorities share more in common, culturally and genetically, with Tibetans and Southeast Asians than with heartland Indians. They have endured generations of neglect. They have waged years of guerrilla war for independence or greater autonomy. A decade ago, during such uprisings, I would not have been able to walk through.

Today, a different violence grinds on.

The rich primary forests cloaking northeastern India are unraveling fast. Fragmented by population growth, the old trees are succumbing to expanding rice fields. Illegal logging, the charcoal trade, and mining scrape new roads into the hill backcountry. Walking through such landscapes was like falling in love, late, with a cancer patient.

You held her hand as you would a glistening leaf. You knew it was provisional.

THE MOST EFFECTIVE defenders of the northeastern highlands were battalions of Haemadipsa ornata.

They had five pairs of eyes, left painful bites that hemorrhaged for hours, and ingested several times their own body weight in blood at one meal. Stinging land leeches made no discernable sounds. Instead, they elicited them.

Saviour Shadap, an ethnic Khasi guide and walking partner, sprinted across a bog writhing with thousands of the predatory worms, shouting: “Ah! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!” (His vocalizations did not help.)

Hormazd Mehta, my Zen walking partner through much of the northeastern hills, spotted a leech crawling between his bloodied toes: “Hey little friend. Where are you? There? No, there? No, there? Hey. Where are you?”

Priyanka Borpujari, another walking partner, threw pinches of salt onto the leeches suction-cupped to my back (leeches do not like salt). Borpujari: “Got that one!” Me: “Anymore?” Borpujari: “Yup, got another!” Me: “Anymore?” Borpujari: “Yes—wait, no, a mole. That’s just your mother.”

WE POLED a tea-colored stream on a bamboo raft.

We balanced on mossy logs spanning break-bone ravines.

We forded the wild Jiri River, and then crossed the Makru River, and climbed canyon trails so steep that just staying upright required total concentration. Any multi-tasking—an untimely breath or eye-blink—risked a fall.

Two months in, we walked 24 miles in a single day to arrive, stinking and rubber-legged, at a nighttime village. Like most ethnic Naga communities, it clung to the summit of a sheer ridgeline as a defense against old headhunting raids. It lived off the grid, curtained from the world by six feet of annual rains, marooned in the cloud forests of Manipur. I sat on its mud promenade, catatonic with exhaustion. There was gospel music.

A dapper man with a guitar case strapped to his back appeared. He took us to water.

“We could have offered you better,” he apologized with the manners of a prince, “had you given us notification of your arrival.”

This was Azuram.

THE RESIDENTS of Azuram were radicals.

Their slash-and-burn rice farms were depleted by necessity. The village had grown from 17 to 49 households in seven decades. Instead of resting their jungle fields for ten years, as their ancestors had, the farmers replanted every five. Yields were dwindling. The groves of wild oranges—Citrus indica, the antique source of the modern fruit—had caught blight. Little timber remained to cut be in the forest. Rural lifeways were on the wane and the kids were leaving for town.

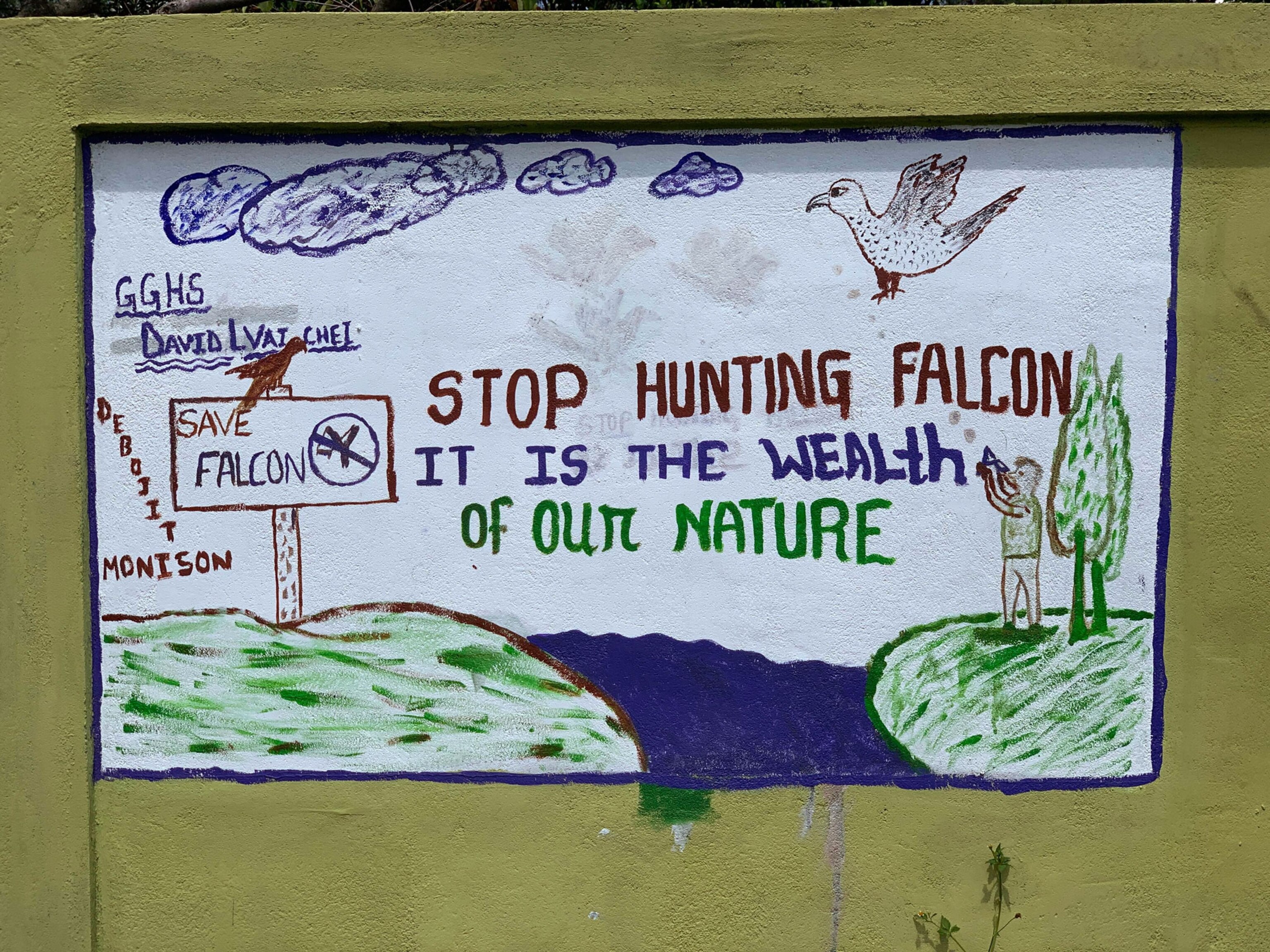

So Azuram declared itself an ecological zone.

“It will benefit not just our community,” said Nehemiah Panmei, the honorary wildlife warden of the village and the organizer of its Rainforest Club. “It will be good for all humanity.”

Panmei was a global thinker at the uttermost end of the Earth.

In 2016, he convinced the village to set aside half its land, nearly three square miles, as a communal forest preserve. Elephants were long gone. But the jungle still sheltered wild boar, a species of deer, porcupines, and jungle fowl. Someone had bought a tortoise at a bushmeat market and released it at Azuram. About once a year, a relict tiger strolled through.

The villagers had built an iron wildlife observation tower. It was for ecotourists to enjoy the stunning views.

“So far, nobody has come,” Panmei admitted. “But we’re still hopeful.”

Captains of industry might one day invest in Azuram, Panmei said, as part of a corporate social responsibility deal. He spoke of getting the United Nations involved. (For Baga Dima, a resourceful village in India, sustainability is rooted in tradition.)

The local Naga people were religious minorities in Hindu India, members of the American Baptist Mission. They had converted in the 1930s and ceased headhunting their enemies. Now, they listened to Christian Rock on radios. Women weaved shawls on household looms. Entertainment was a slanting dirt volleyball court where foul balls bounced hundreds of feet down the slopes.

I asked Panmei where he got his green ideas. He quoted Psalms 94:5: “In His hand are the depths of the Earth, and the mountain peaks belong to Him.”

“AZURAM NEEDS a road. Road, road, road,” lamented Hormazd Mehta, my walking partner, who worked as a cultural guide in the region.

And of course, it was true.

We exited the hills of northeastern India along the Azuram track. It was 18 miles of landslides indifferently linked by a tractor trail. During the monsoons, the village sick were carried out on litters. It was hard to imagine foreign birdwatchers there. But you never could tell about dreams or roads. Plodding through mud and butterflies, I imagined the tribal Baptists from Manipur benefiting their co-religionists at the distant source. A little reverse missionizing. Generosity toward strangers. Respect for nature. Women and men toiling side by side. The children listened to.

We walked to the town of Tamenglong. The sound of the world was waiting.

Motorbikes trailed blue smoke around mildewed buildings. Motorized rickshaws beeped. Mehta posed for a photo under a downtown sign that announced the district name, and it was Utopia.

Paul Salopek won two Pulitzer Prizes for his journalism while a foreign correspondent with the Chicago Tribune. Follow him on Twitter @paulsalopek.