Pearl Harbor survivors forgive—but can't forget

On December 7, 1941, Japan’s deadly attack catalyzed a nation, shattering America’s sense of invincibility and pulling the country into war. Today the site is a symbol of service, science, and healing.

It’s still there. The U.S.S. Arizona is still resting on the seafloor in Pearl Harbor, asleep in 40 feet of gray, silty water.

It’s been there since the morning of December 7, 1941, when 353 Japanese planes mounted a surprise assault on American naval forces stationed in Hawaii. The attack killed 2,403 United States personnel, injured 1,178, drew the United States into World War II, and altered the course of history forever.

Nearly a thousand of the 1,177 servicemen killed aboard the Arizona remain entombed in the battleship's slowly rusting hull. The number of living survivors has dwindled to five. Yet the ship’s enduring existence offers a tangible assurance—a promise that the day of infamy will never be forgotten.

There will be no shortage of commemorative events this week, from reunions and wreath layings to concerts and parades. But the Arizona is still the anchor of the site: a symbol of sacrifice, a source of scientific inquiry, and, increasingly, a site of reconciliation.

Survivors’ Stories

“It was a hell of a day,” says Donald Stratton, a 94-year-old survivor of the attack. “It started out real nice, but then—well, you know the rest.”

For Stratton, a 19-year-old seaman at the time, “the rest” involved a miraculous feat of survival. When a 1,760-pound Japanese bomb hit the Arizona, it ignited 180,000 gallons of aviation fuel, 500 tons of gunpowder, and more than a million pounds of munitions. The explosion engulfed the ship in a 50-foot fireball that ripped through the anti-aircraft platform where Stratton was standing. Nearly 70 percent of his body was burned. “I still don’t have any fingertips,” he says.

Stratton spent a year recovering in a military hospital, then—improbably and inspiringly—reenlisted in 1944. “Partly out of a sense of revenge,” he says. “But over the years I’ve come to realize, those [Japanese] pilots were just obeying commands, same as we were.”

Stratton’s new book, All the Gallant Men (co-written with Ken Gire), is the first memoir by a U.S.S. Arizona survivor. But he’s not the ship’s only author. Lauren Bruner, a 21-year-old serviceman at the time of the attack, has written a novel based on his experience, Second to the Last to Leave U.S.S. Arizona (co-written with Edward McGrath and Craig Thompson).

“I remember I got up that day and had breakfast,” recalls the 96-year-old. “That night I was supposed to have a date with my gal. But I didn’t quite get there.”

When the bomb struck the Arizona, the explosion trapped Bruner and six other men inside a metal box on the forward mast. Like Stratton, Bruner was burned over more than two-thirds of his body. But a sailor on the deck of a nearby repair ship spotted the men and threw a line to the burning vessel. Bruner and his team managed to cross to safety, despite the charred skin falling off their bodies.

Half a year later, after stints in two hospitals, Bruner was reassigned. His second tour of duty took him to the Aleutian Islands, the Philippines, and Nagasaki, Japan.

Despite the horrors he survived at Pearl Harbor, the site remains a haven for him. Heading there this year to join the Arizona’s other survivors, he says, “is like going back home again. I know them so well.”

Underwater Science

The United States Navy oversaw the wreck site until 1980. Since then it’s shared the task with the Submerged Resources Center (SRC), a crack team of National Park Service underwater archaeologists and photographers.

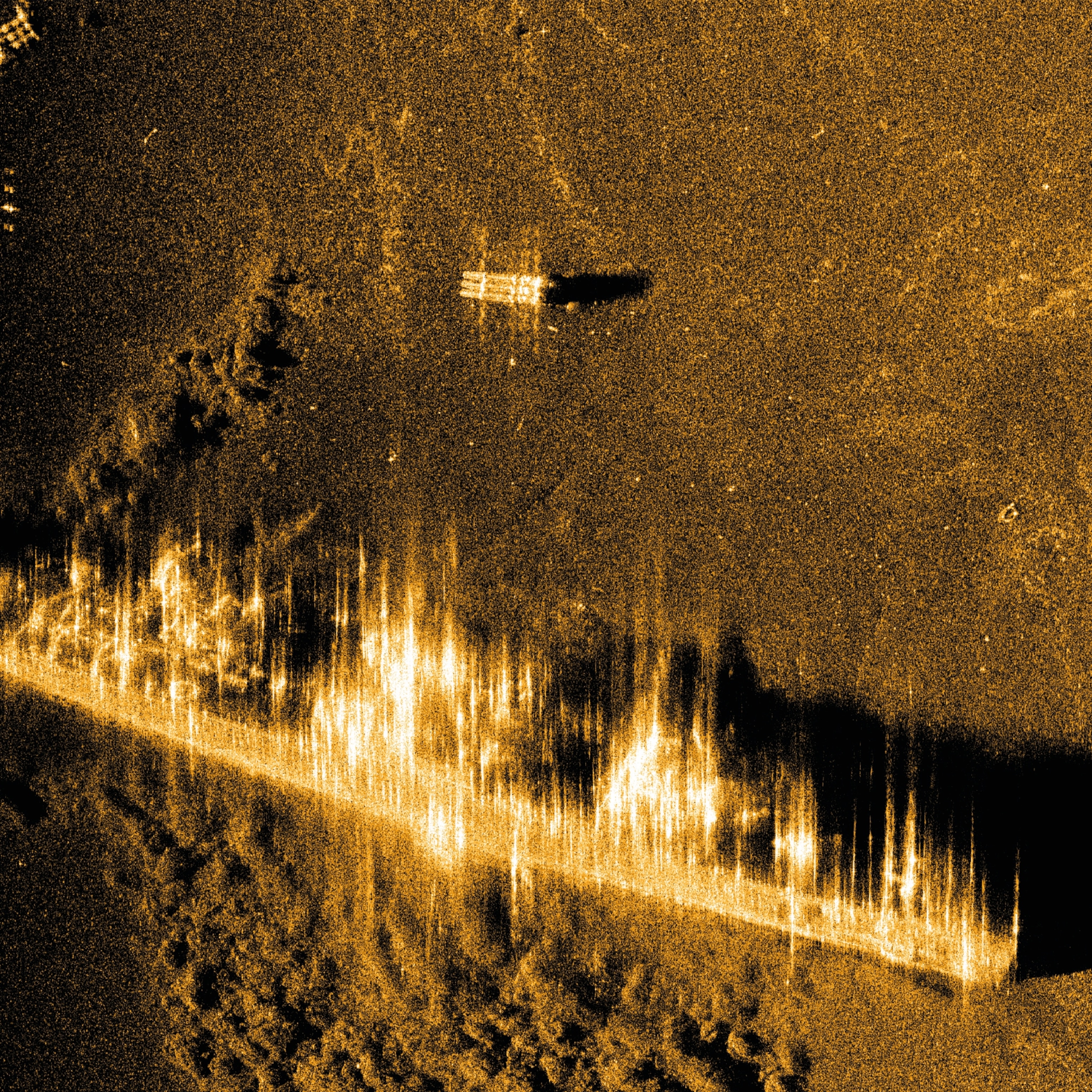

Brett Seymour, the SRC’s deputy chief and photographer, has been diving at the site for nearly 20 years. The Arizona, he explains, was first mapped in the early 1980s. Over the next two decades, the SRC performed a series of corrosion studies, oil analyses (the Arizona still leaks five to eight quarts a day), and interior investigations to figure out how long the ship’s superstructure might last. (Several hundred more years, says Seymour, thanks to an unusual lack of oxygen, rust, and corrosion.)

Interpreting and managing the site is done through research, photography, and—using sonar, photogrammetry, and underwater lasers—digital mapping. Last year the SRC unveiled a three-dimensional print of the ship. This year it will present 3-D prints to Stratton, Bruner, and the other survivors.

Initial exploration of the ship occurred just a month after the Japanese attack, when Navy divers salvaged guns and hardware from the Arizona, along with safes, record books, and live ordnance. Since then, divers haven’t been allowed inside, out of respect for the ship’s entombed servicemen.

But in 2000, after getting permission from the Arizona’s survivors, the SRC began sending remotely operated vehicles inside (including a specialized one, operated in conjunction with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, which helps penetrate sunken vessels). The SRC’s remote imaging has revealed a site littered with poignant links to everyday life: cooking pots on the deck, crockery, silverware, Coke bottles, and shoe soles, among other things.

“What’s most amazing to me about the Arizona is that it’s still there,” says Seymour. “When you see it up close, you’re not just seeing where something happened. You’re seeing what happened there.

“This iconic shipwreck is probably the single most tangible touchstone we have for World War II—a real, physical representation of an event. We don’t have many of those in our history.”

An ambitious new study of sediment, soil, water, and dissolved oxygen at the site is slated to begin on December 9. There’s no knowing what it will turn up, says Seymour. But he and his SRC colleagues are hopeful.

Learning to Forgive

Daniel Martinez is the Park Service’s chief Pearl Harbor historian. He says a lot has changed since 1984, when he started working at the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument.

“In 1991,” he says, “we hosted 6,000 Pearl Harbor survivors and their families. This year we’ll be lucky to get 200.”

But the biggest change isn’t quantitative.

“The memorial has changed a lot because the country has changed a lot,” says Martinez. “As the people who build a memorial fade, the memorial reshapes itself in its interpretation and meaning. In the case of the U.S.S. Arizona, it’s slowly changed from a war memorial to a peace memorial.”

Built in 1960 and ’61, the monument was dedicated in 1962—the first national WWII memorial in the U.S. For those first few decades, Martinez says, “there was a lot of anger, hurt, and hatred at what had occurred in the Pacific with the Japanese and Pearl Harbor.”

A shift from recrimination to reconciliation began in 1991. That’s when President George H. W. Bush, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the attack, gave a speech that included the line “I have no rancor in my heart toward Germany or Japan—none at all.”

That, says Martinez, “was a president advising his fellow Pacific veterans that the war was over—and that they needed to move on. He nullified a lot of anger and gave us the ability to use his words as a policy. It became the way that we conducted ourselves from that time forward.”

When President Bill Clinton arrived in 1995, on the 50th anniversary of the war’s end, his speech continued in that vein. And 2016 marked the next step in the progression: On December 26, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Pearl Harbor with President Obama, becoming the first sitting Japanese leader to survey the site. (In doing so, he reciprocated a historic trip the U.S. president made to Hiroshima back in May.)

Martinez says that all of these things show the memorial becoming an ode to inclusiveness and shared experience.

“A lot of people don’t realize that [the memorial] is not just for the U.S.S. Arizona and its crew,” says Martinez. “It’s a memorial to all of those killed at Pearl Harbor, including the Japanese and the 49 civilians who suffered friendly fire.”

The key, he says, is to remember that “we need to celebrate 70 years of peace between Japan and the U.S. This relationship we’ve developed is moving us forward. The point is not to forget what happened in 1941. But to forgive what happened back then shows the greatness of our nation. In this case, both nations’ greatness.

“We’ve had a Japanese tea ceremony on the memorial. A prayer service. Our museum has become a place of healing. That’s something I never thought I’d see. But it’s happening.”