How hieroglyphs became the sacred script of the ancient Egyptians

The Egyptians believed that hieroglyphs offered magical protection to people in this life and the afterlife, and inscribed the signs on monuments, statues, funerary objects, and papyri.

The beginnings of hieroglyphic writing date back to the birth of ancient Egypt at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. It was in this period that a series of figurative signs first appeared, mostly depicting animals. Some signs were engraved on rock massifs, such as the recently discovered El Khawy inscription, while others were marked on stone statues (the three limestone colossi from the shrine at Coptos are impressive examples). Figurative signs have also been found on small ivory labels and vessels placed in the tombs of early rulers, such as the labels found in tomb U-j at Abydos. Whether these early signs should be considered writing proper or designating concepts without direct association to language is still an open question among researchers.

The first inscriptions that definitely meet the criteria of hieroglyphs date to around 3150 B.C. They show various characteristics of hieroglyphic writing. For example, there are logograms—signs that denote the name of the object they represent—together with other signs whose value is purely phonetic, like the letters of our current alphabet. Often, these phonetic signs originated from the first logograms. For example, 𓂋 (the mouth symbol),which in Egyptian is called ra, was used to represent the phoneme r in other words that included that sound.

The earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions were very brief, in most cases expressing the name of a king or a place. They were often inscribed on ceremonial objects such as palettes. On the Narmer Palette, for example, we find the name of Narmer, considered the first king of unified Egypt. The name is written using two signs: 𓆢 (catfish) and 𓍋 (chisel), which appear within a sign called serekh, which symbolizes the royal palace and thus denotes kingship. In a similar way, the names of cities are represented within a sign that symbolizes a walled enclosure. Both the serekh and this enclosure sign, although not pronounced, indicate visually which semantic category the name they contain belongs to. As the writing system developed, this semantic classification was indicated by unpronounced signs placed at the end of each word, the so-called determinatives or classifiers.

Sacred writing

In ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs were much more than simple vehicles for communicating a practical message. The Egyptians called their hieroglyphic signs medu netcher—“words of the god” or “sacred words”—since they believed that hieroglyphic writing was an invention of the god Thoth and was imbued with creative and magical power. Egyptians didn’t create texts simply to be read; more importantly, they created them to ensure the magical and protective effect of the divine words. This explains why the signs were written on not only papyrus scrolls and stelae but also architectural monuments, statues, furniture, funerary objects, and everyday items including clothing.

The Narmer Palette

The hieroglyphs inscribed next to the two fleeing figures may refer to the names of two cities conquered by Narmer.

Eternal protection

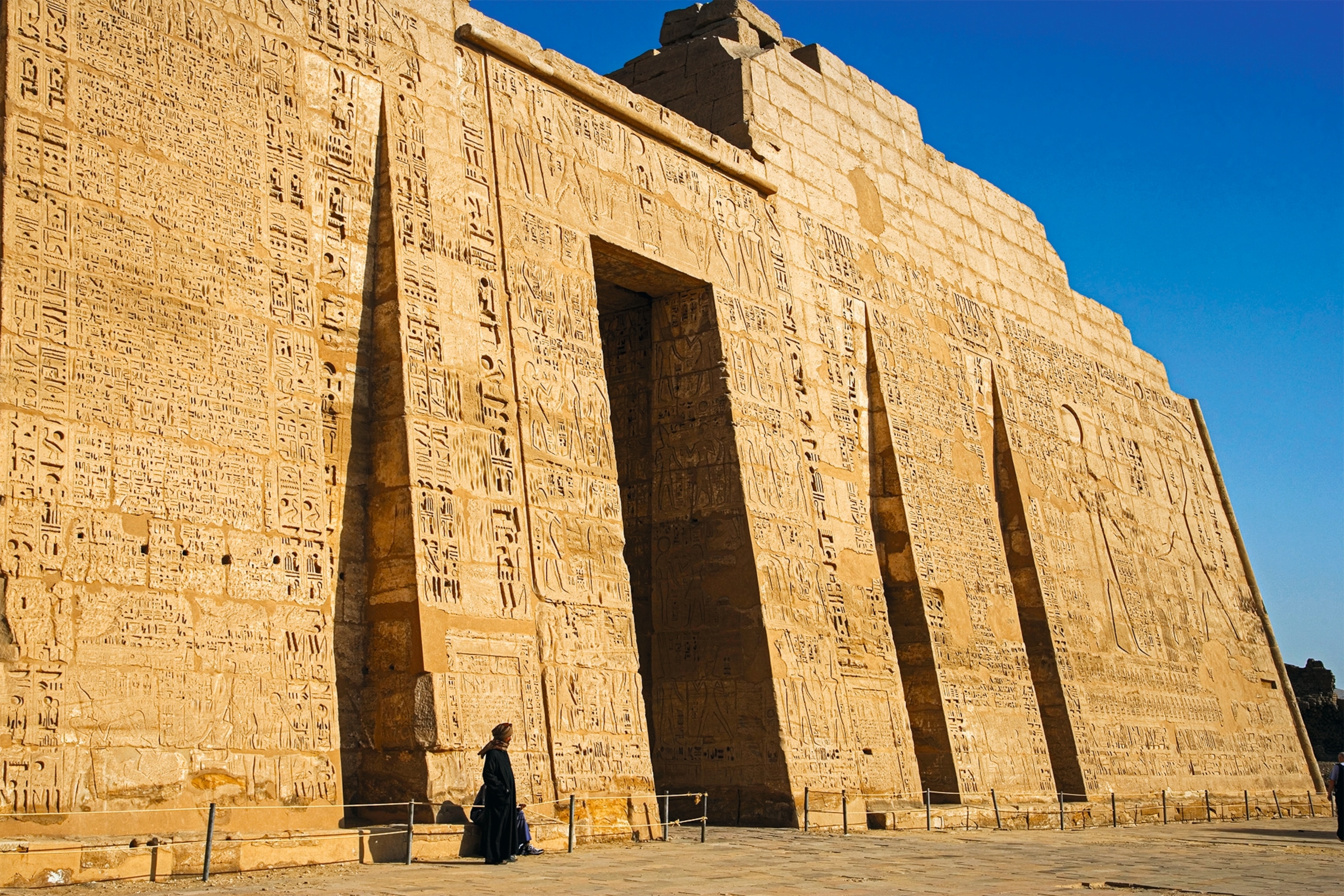

It was typical for the walls of Egyptian temples to be completely covered with hieroglyphs, and many examples have been preserved. Although the visual impact is astonishing, the purpose was not merely decorative. Rather, the use of hieroglyphs in temples was related to the role of temples in the Egyptian worldview. The word “temple” in ancient Egypt was menu, derived from the verb “men,” meaning to remain, to establish, to be permanent. The stone temples of ancient Egypt were built with the idea that they would last for eternity, and the texts inscribed on them reflected this idea. The architecture of the temple was believed to represent in miniature the structure of the universe, with everything outside the sacred precinct representing the primordial chaos prior to creation. The outer facades of Egyptian temples were often decorated with magnificent reliefs depicting the pharaohs battling their enemies: an earthly clash that mirrored the struggle between order and chaos. Through this decoration, the religious and historical planes merged.

Prayers on the walls

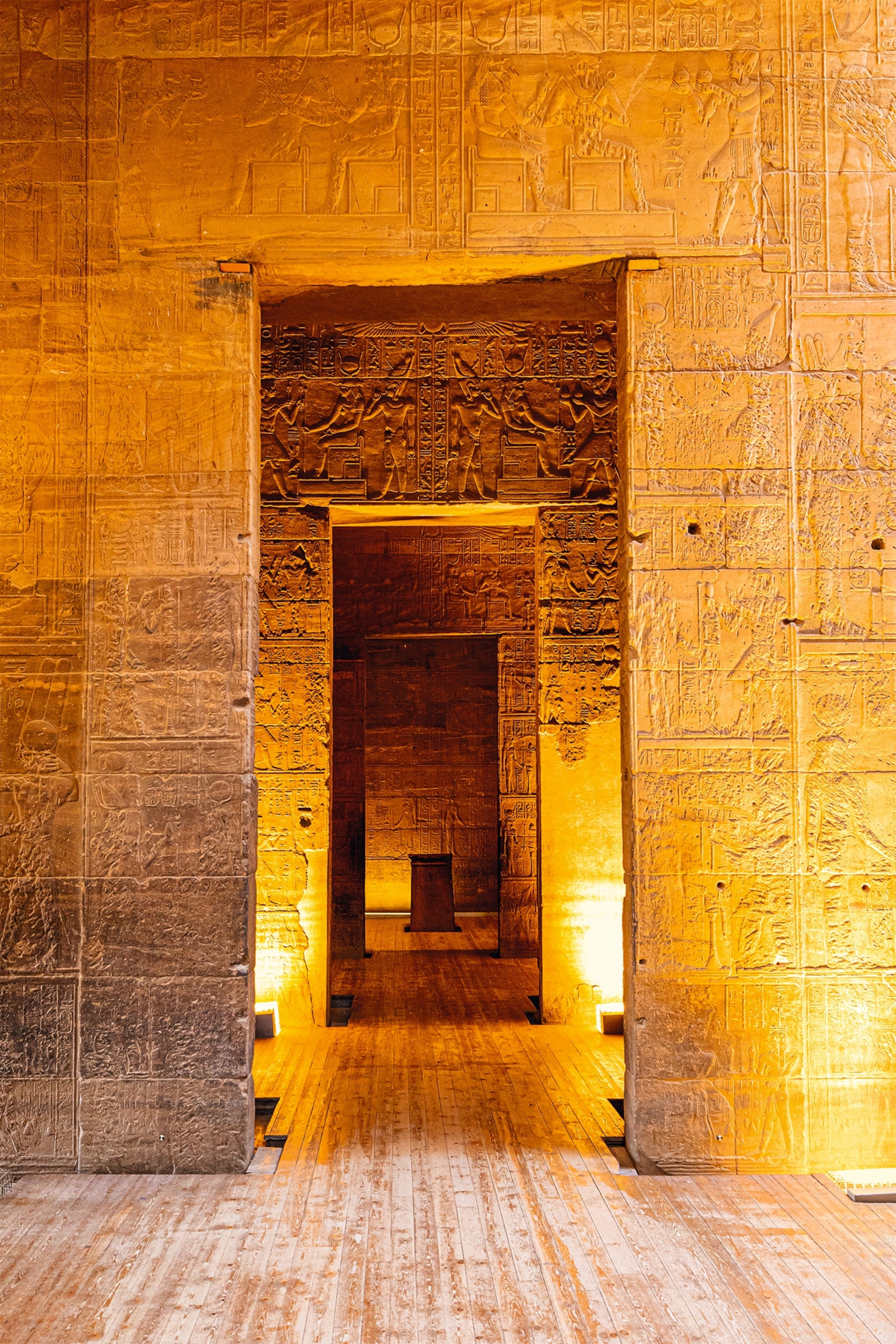

The interiors of temples and tombs were often covered floor to ceiling with hieroglyphs. Inscribed within the temple chambers were the ritual texts that priests would recite in front of statues of the gods. Around the doorways were texts indicating which grades of priests within the priestly hierarchy were allowed access to the next chamber and what purity requirements they had to meet.

Inside the tombs themselves, there are hieroglyphic texts related to rituals designed to keep the deceased’s memory alive. With many royal tombs, these texts transformed the underground space into a physical representation of the underworld, into which the pharaoh crossed when he reached the afterlife.

Instruction manuals on the wall

(Do these ancient Egyptian inscriptions mention Moses by name?)

Statues and stelae

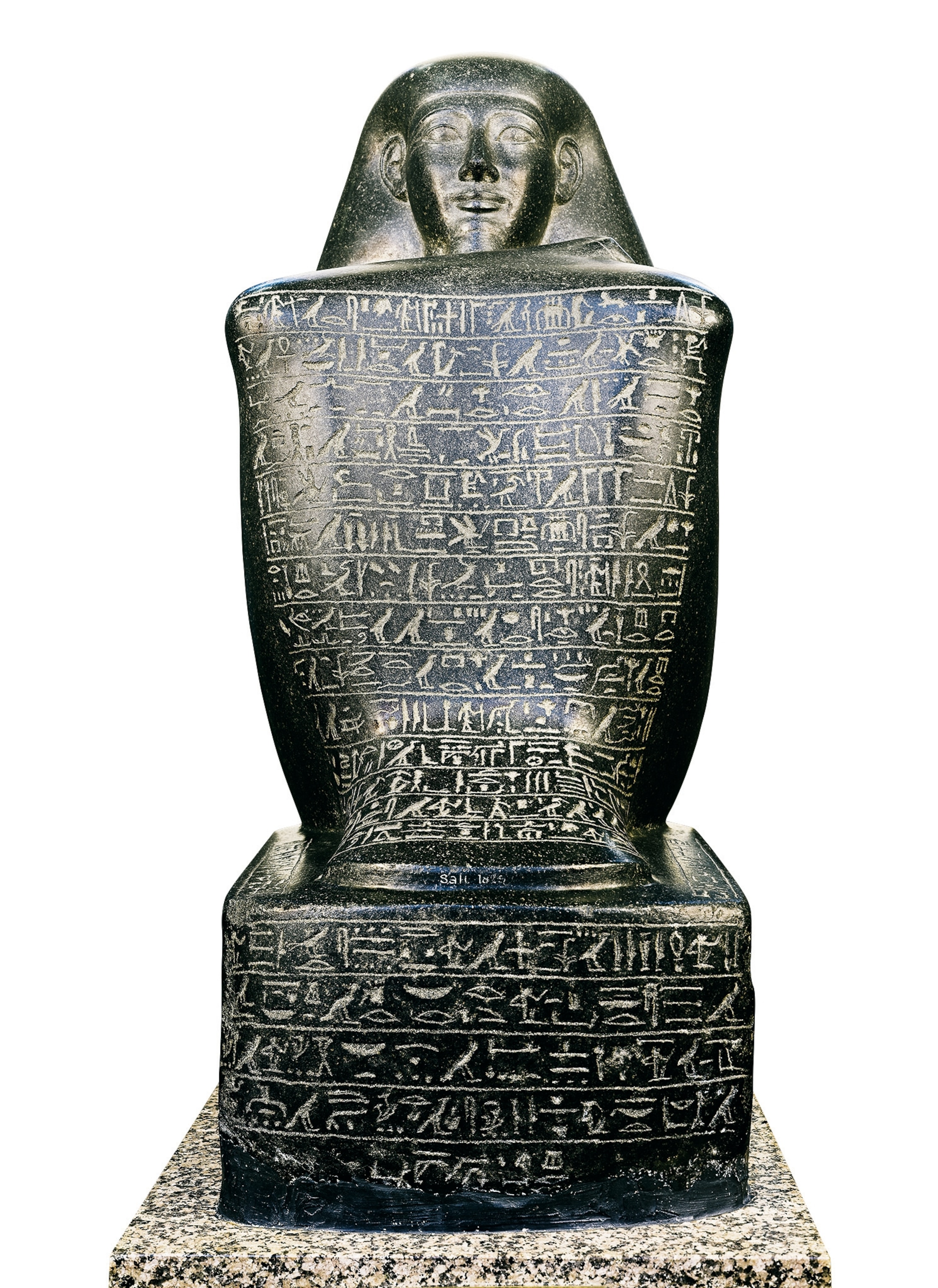

In addition to covering the walls of temples and tombs, hieroglyphs were inscribed on a wide variety of objects. Stelae, large slabs usually made of stone, could be inscribed with extensive religious texts, royal decrees, or accounts of military campaigns. Although the text on statues was often limited to the name, title, and kinship of the person represented, sometimes long texts of notable literary quality are found engraved on statues. These texts could include a detailed biography of the person represented or genealogy going back several centuries. Some statues were specially designed to provide a large, flat surface area on which to inscribe long texts (for example, the so-called block statues, which are cube-shaped from the chest down). The statue of Nebmerutef, an 18th-dynasty scribe, demonstrates another ingenious method for inscribing text on a statue. Nebmerutef is depicted reading a papyrus under the supervision of the god Thoth. The papyrus is unrolled on his lap, and on it is inscribed a text detailing his titles and the actions he had performed in the service of the king.

Objects used in burial practices were often inscribed with hieroglyphs too. In this case, the aim was to ensure that the name of the deceased would be remembered forever and to provide them with the protection they needed on their journey to the afterlife. To achieve this, magical-religious formulas taken from texts such as the Book of the Dead were inscribed on coffins, boxes, and funerary masks. From the 30th dynasty onward, it became customary to inscribe these formulas on the linen bandages that wrapped the body of the deceased. Being in direct contact with the mummy, they were believed to offer additional protection beyond that of the amulets wrapped in the bandages. Formulas also appear on the wooden doors of some tombs, such as that of Sennedjem in Deir el Medina, where they had a defensive role, protecting the most vulnerable part of the tomb.

The magical effect of hieroglyphs was not limited to the afterlife. Egyptians wore amulets decorated with the sacred writing. There’s evidence that during the Third Intermediate Period (circa 1075 to 715 B.C.) people would roll up long, narrow strips of papyrus inscribed with magical formulas and wear them inside necklaces. One of these strips, preserved in the British Museum and likely worn by a baby, measures around 20 inches long, which may have corresponded to the size of the wearer.

(What it was like to see King Tut's tomb just after it was opened)

Egyptian-style shorthand

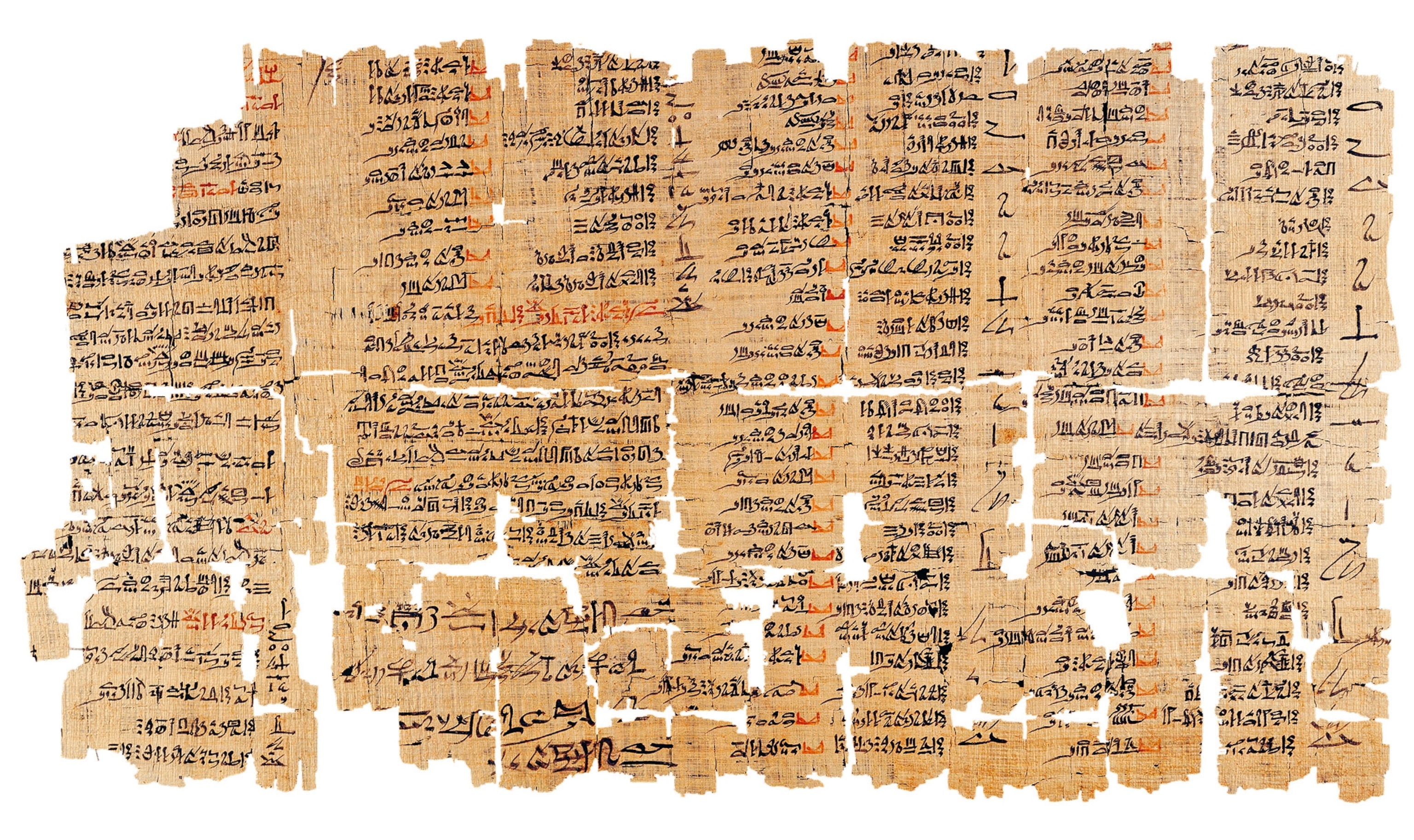

Although the Egyptians believed their hieroglyphic writing had magical properties, they also used a simplified form for secular purposes, both administrative and literary. The simplified signs could be written quickly, in one or two strokes, using a brush dipped in ink. By the 2nd dynasty (2890 to 2686 B.C.), this cursive writing had been standardized into the so-called hieratic script. To make writing faster, certain groups of two (or more) signs were joined up using ligatures so they could be written with a single stroke of the brush.

The most common medium for hieratic writing was papyrus. The oldest surviving papyri date from the reign of Khufu (circa 2589 to 2566 B.C.). These fascinating papyri make up a journal belonging to an official named Merer, who headed a large team of builders working on the Great Pyramid at Giza. In the papyri, Merer records details about the distribution of the stone blocks for the building work, the quarries they came from, and how they were transported and paid for. From the Middle Kingdom onward, hieratic writing was also used to scribe literary texts on papyrus.

In the seventh century B.C., with the rise of the 26th dynasty, an even more cursive form of hieratic script developed. The signs in this script, known as demotic, have such a simplified visual form that their hieroglyphic origin isn’t obvious. Demotic script was used until the middle of the fifth century A.D., 50 years after the last dated hieroglyphic inscription. By this point, the Egyptians no longer understood the hieroglyphic writing system that had defined the millennia-old pharaonic civilization and still adorned the temples and tombs of their country.

Hieroglyphic healing