Who were the Phoenicians? Archaeologists are unraveling the mystery.

Despite being known as masters of trade, these seafarers were never a single collective. Different groups built powerful cities across the Mediterranean and the latest research shows they date back earlier than we thought.

The Phoenicians never existed. Or, at least, the people we now know as Phoenicians didn't use that name for themselves. While they identified as inhabitants of a particular city—Tyre, Sidon, Gebal (known by the Greeks as Byblos), Berytus (Beirut), or Aradus (Arwad)—they never identified themselves as a Phoenician collective. Each Phoenician city was independent: The inhabitants spoke different dialects and each city had its own pantheon, institutions, and an autonomous international policy.

The term "Phoenician (Phoinikè)" is a Greek word first used in Homeric poems composed around the eighth to seventh centuries B.C. It refers to the people and region along the modern-day Lebanese coast. It's not clear why Phoinikè was chosen; its meaning of a reddish purple may refer to the perceived tanned skin tone of the Phoenicians or, more likely, the valuable purple dye they used to color their textiles.

The erroneous view of the Phoenicians as a single people also led to the assumption that, at some point in the past, the founders of the Phoenician cities had moved to the coast of present-day Lebanon from somewhere else. Jewish, Greek, and Roman authors formulated various theories regarding the origin of the Phoenicians based on this assumption.

(2,600-year-old wine 'factory' unearthed in Lebanon)

One of the most widespread views is found in the biblical Book of Genesis, the definitive version of which was probably written in the sixth century B.C. There, it is stated that the Phoenicians were descendants of Sidon, son of Canaan and grandson of Ham. Through this association, the biblical writers include the Phoenicians within the genealogy of humanity. Ham, son of Noah, was considered the progenitor of the African peoples; Ham’s brother Shem the progenitor of the Semitic peoples; and the third brother, Japheth, the progenitor of the peoples of central and eastern Asia. Curiously, the biblical writers saw the Phoenicians, who, like them, spoke a Semitic language, as descending from Ham rather than Shem.

Greek and Roman authors put forward various hypotheses about the origins of the Phoenicians. According to Herodotus, they came from the Erythraean Sea, located, according to some sources, between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Strabo and Pliny the Elder pointed to the Persian Gulf region as the Phoenicians’ original homeland. Justin records that the Phoenicians had to migrate toward the Levant because of an earthquake in their country of origin, although he doesn’t indicate when or where this earthquake took place. It may have been in Syria or some region of Mesopotamia, or perhaps on the shores of the Red Sea.

'Richer in fishes than in sand'

structured as a letter written by an Egyptian scribe, although it is more likely to be a literary composition. One section is dedicated to the cities of the people the Greeks later called the Phoenicians: “I will tell you of another mysterious city. Byblos is its name; what is it like, and its ... goddess, once again? You have not trodden it. Come teach me about Berytus, and about Sidon and Sarepta ... They tell of another city in the sea, Tyre-the-port is its name. Water is taken over to it in boats, and it is richer in fishes than in sand.”

The text offers insight into the Egyptian administrators’ knowledge of Canaan. It references its roads, the layout of its cities, and the wealth of the region a few centuries before Phoenicia would begin its golden era of trans-Mediterranean trading.

Clues from archaeology

However, the latest historical and archaeological data contradict all of these ancient hypotheses about the origin of the Phoenicians. Biblical and Greco-Roman traditions could only speculate about the Phoenicians, a people whose true history was largely unknown. But archaeological discoveries are uncovering evidence of what really happened.

While the ultimate origin of the people who later became the Phoenicians is lost in the mists of time; by the period in which their great cities arose, they were established in the Mediterranean Levant alongside neighboring Canaanites. Recent research shows that the Phoenicians were direct heirs of a culture that had been based in the Levant since at least the third millennium B.C.: that of the Canaanites.

(A Canaanite palace was abandoned 3,700 years ago. Archaeologists finally know why.)

The Canaanites are most widely known through the Bible, where they are described as the Indigenous people of Palestine who resisted the Israelite conquest of their territory, traditionally dated around 1200 B.C. However, Canaan’s heyday came earlier in the second millennium B.C., when Canaanite culture spread throughout the Levant, from present-day Israel and the Palestinian territories to southern Syria. The various Semitic peoples of the area created a mosaic of city-states in which they spoke different dialects of the same West Semitic language. These city-states maintained trading relations with the other territories of the eastern Mediterranean. The strategic value of the Canaanite territory and the abundance of particular resources, including cedar wood, meant that the empires of the Near East and Egypt were constantly trying to control the territory. For almost three centuries, pharaohs of Egypt’s New Kingdom ruled Canaan.

Canaanite roots

There is a clear continuity between the Canaanite culture of the third and second millennia B.C. and the Phoenician civilization of the first millennium B.C. Archaeology has shown that Phoenician cities such as Gebal and Tyre were occupied almost continuously from at least the Early Bronze Age (circa 3500–2000 B.C.) by the ancestors of the people later known as the Phoenicians. These cities were located on promontories or islands, allowing them to control the surrounding agricultural land and the natural bays and ports,which were key to their trading activities. According to written sources, around 1200 B.C. the region experienced a moment of crisis due to invasions by the so-called Sea Peoples, groups of pirates from the western coasts of Anatolia and the Aegean Sea area. While archaeological evidence uncovered so far attests to disruptions in trade, the Phoenicians continued trading.

(Purple Reign: A passion for purple built the Phoenicians' vast trading empire)

Tyre, an age-old city

From there, the team was able to dig down to the earliest strata, which confirmed that Tyre was founded between the end of the fourth millennium and the beginning of the third millennium B.C., probably as a port on the ancient network known as the Byblos Run, a route trading oil, wine, and cedar wood among Mesopotamia, Turkey, Crete, Cyprus, and Egypt.

The idea that the Phoenicians were a powerful trading people, far from being a novelty of the first millennium, is already attested to in tablets written around 2300 B.C. discovered in the Syrian city of Ebla. These texts show that Gebal was already acting as an intermediary in international trade between the Mediterranean and the cities and kingdoms of Asia, particularly in textiles, metals, and wood. Later, during the Late Bronze Age (circa 1600 to 1200 B.C.), Gebal, Sidon, and Tyre, together with Ugarit, were the main commercial ports of the eastern Mediterranean, vital stops on the land and sea routes between Egypt, Mycenae, Syria-Palestine, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia.

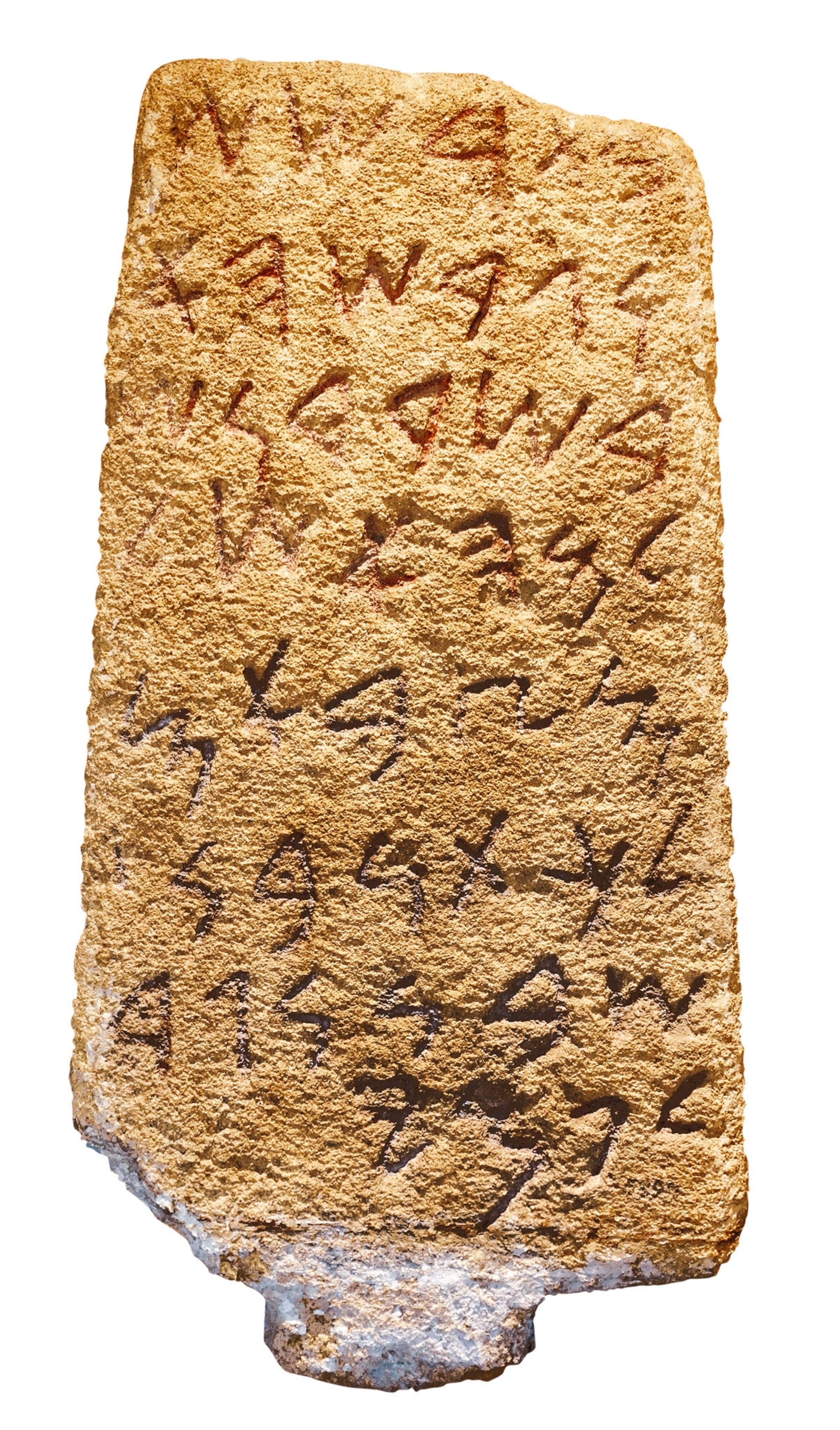

Evidence indicates that the various dialects used by the Phoenicians belonged to the Canaanite dialect group of the northwestern Semitic languages. The closest languages to Phoenician are Hebrew and Aramaic. The Phoenicians can even be credited with playing a major role in the invention of the alphabet, one of the most significant advances in human history. Their alphabet built on and consolidated earlier forms of writing found in the so-called Proto-Canaanite inscriptions from sites including Izbet Sartah and Serabit el Khadim, as well as the cuneiform alphabet of Ugarit.

A distinct culture

Phoenician religion, too, seems to have evolved largely from the ancient Canaanite religion. They continued the worship of traditional Canaanite divinities such as Baal, El, Anat, Astarte, Resheph, Kothar, and Baalat Gebal (Lady of Byblos). Later the Phoenician cities adopted additional deities as a result of their contact with other groups including Assyrians, Babylonians, Arameans, Hebrews, Philistines, and Greeks. They also started to worship divinities such as Melqart and Tanit, who were not included in the Canaanite pantheon of the second millennium B.C. So, the Phoenicians developed their own religion but maintained a strong continuum with the previous Canaanite culture.

The gods of Canaan

Thanks in part to the turbulence caused by the Sea Peoples, Phoenician cities began to evolve and thrive after 1200. The Sea Peoples had destroyed rival ports, such as Ugarit, which were not rebuilt, allowing the Phoenicians to monopolize trade with Cyprus, Greece, and Egypt. The rise of the Phoenician cities was also made possible by the demise of the Egyptian and Hittite empires. By the 10th century B.C., Tyre was the main commercial power in the Levant. Soon after, a colonial expansion began that would take Phoenician culture westward to the other side of the Mediterranean, the Iberian Peninsula, and the Atlantic coast of Africa.