These ruins are a potent legacy of war on the landscape

Constructed when Hitler's armies threatened the future, many of these scarred structures across northern Europe represented a last line of defense against invasion. This photographer spent five years documenting their last stand.

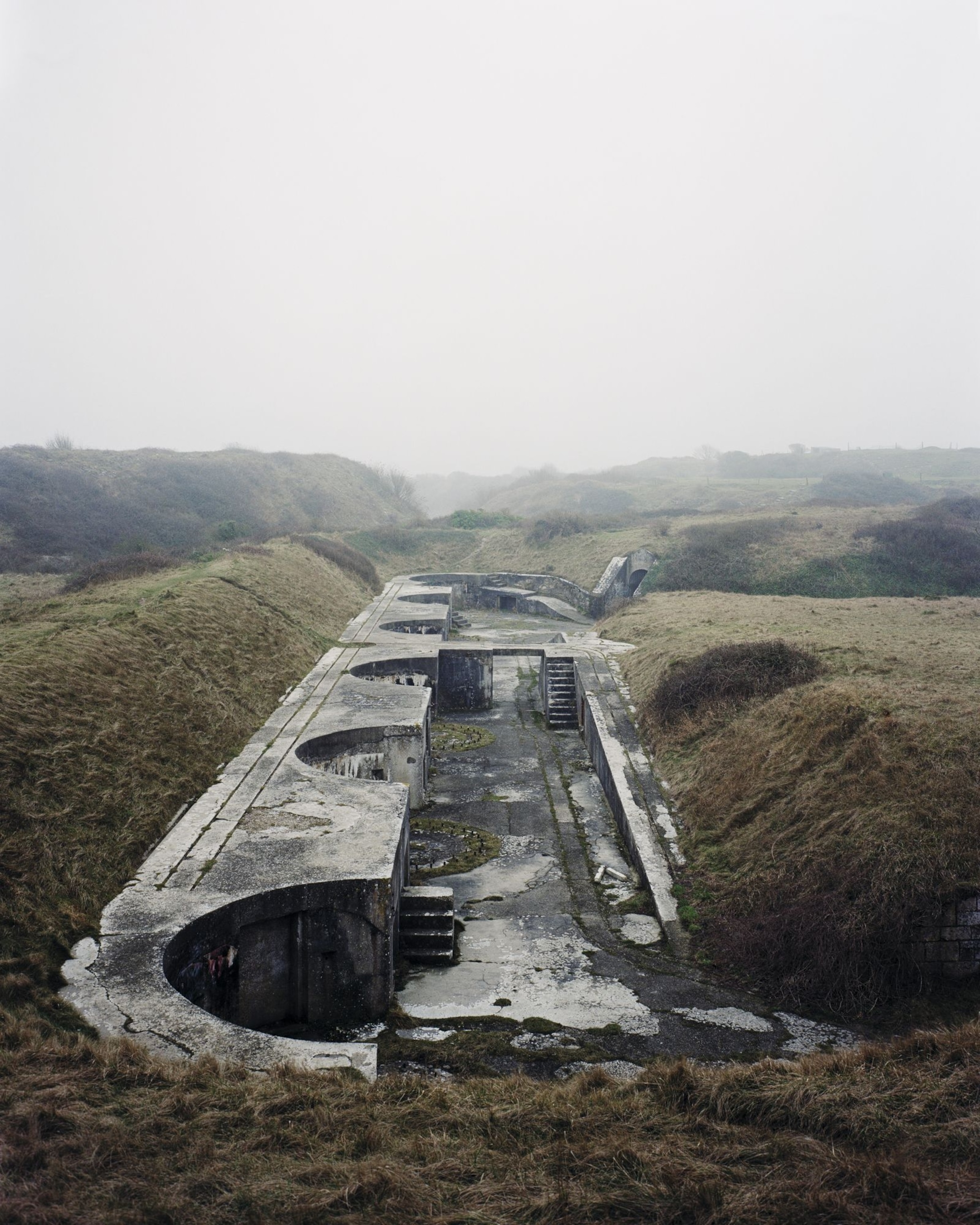

At a glance the view could be of any beach or cliff or headland, on the edge of any northern sea: cold and hard, with big horizons, rocks oiled with salt and moisture. Let that glance linger, though, and you start to see them. A slot in a cliff that’s a little too straight to be natural. Boulders on the beach that, with scrutiny, aren’t boulders at all. That line of rocks exposed at low tide spaced with tell-tale regularity, straight edges cut by human hand.

(11 Otherworldly Pictures of Abandoned WWII Bunkers)

During the European conflict of World War Two, the waters around the British coastline were both its savior, and its warily-watched curse. Stealth attacks by sea could come from any direction, and not just across the 20-mile ribbon of the English Channel—which the Nazis never crossed, except by air, to bomb.

But as the war progressed, no outcome was certain. And in response to Germany's invasion of France in May 1940, as the shadow of Hitler’s armies began to fall closer to British shores, an array of unusual structures were built.

Some are almost invisible. Others are singularly unsubtle and oppressive, breaking nature's organic lines with fantastical forms and impossible situations. Looking at their concrete walls, modern eyes may imagine dystopian barracks, crashed spacecraft or the entrance to some cloak-and-dagger lair.

But their true purpose was, for a generation, all-too dark: Searchlight emplacements, beach defenses, listening stations like upturned dinner plates, anti-tank blocks, ‘stop’ lines of concrete cubes, towering multi-story artillery towers, or squat bunkers with horizontal slots just tall enough for eyes to see out—and just wide enough to swing-fire a machine gun.

How three unlikely allies won World War Two.

A physical legacy of war

When built these buildings were strategically situated. Now, most are approaching 80 years old, and redundant. Overrun by the landscape, they exhibit the signs of an elemental battering, with widening scars and deepening cracks, graffiti tattoos decades old. It is in every sense these structures’ last stand—before they, like those who remember using them for their intended use, vanish into memory.

The Last Stand is the title of a photo study by British photographer Marc Wilson— whose book of the same name comprises a collection of images and essays focussed on documenting this legacy of the war on the landscape. It ranges from bullethole-sprayed bunkers of the Atlantikwall on the continental coast, to the British defenses the conflict itself never touched.

“My aim was to combine memories and the landscape,“ says Wilson. “An attempt to make a document of these locations at the time they were photographed. A time [2010-2015] that itself has become a past as both human and physical elements change these landscapes. That is important to me.”

Lines in the landscape

In Britain alone, thousands of these structures were built. In addition to the so-called coastal crust, the network of ‘pillboxes’ and obstructions that comprised the nation's hardened field defenses ran deep into the country as if punctuating a map of strategic arteries—along waterways, at airports, by bridges.

The many that remain chillingly recount a function that ran every stage of an invasion scenario—from troop training and early warning systems, to tactical defenses and gun emplacements for ground combat.

Since then, the elements—as well as human encroachments—have waged war, particularly on the coastlines. But however caught between land and sea, or structure and rubble, these almost uniformly unappealing constructions retain a power, and a memory of a time when nobody's future was certain.

“It was always meant to be more than a simple photographic recording of the structure alone,” Wilson says. “Rather one that combined the elements of the object, the landscape and time to provide a key to unlock the stories behind.”

Beginning with a test run of images shot on the eroding, sea-battered Norfolk coast in 2010, Wilson began researching and visiting locations to photograph. These were not just around Britain, but on the facing edges of the European mainland from Norway and Denmark to Belgium and France, down as far south as the Franco-Spanish border. Once decided on a location and composition, he would decide on a suitable time of day and tide height, and photograph it “in a fairly rigid manner.”

Wilson says he deliberately avoided naturally thrilling light to avoid distraction from the structure’s own atmospheric texture, describing the feelings in the pictures as “sombre emotions [that] needed no extra dramatic effect… all the drama was already there.”

“It is those feelings that I try to communicate with my photographs,” he says. “Those of a past in the landscape, and a ‘now’ only possible because of what those who have gone before us fought for and sacrificed.”

While the bulk of the work is on British soil, Wilson chose not to focus on just one side of the conflict; many of the defenses he photographed were built by the aggressors. “It was always important for me to create a balanced discourse,” he says. “The human stories behind all the locations have equal importance, and viewers will be able to draw their own view and conclusions—and of course from the knowledge they bring to the work themselves.”

‘Markers in history’

Those who fought in the war itself are now dwindling in number; with the 75th anniversary of its end itself in the past, most veterans may never see the next major milestone. With this thread to living memory increasingly fragile, The Last Stand perhaps takes on added resonance—particularly as the environmental attrition of many of the coastlines on which they stand makes their continued existence temporary, at best. (Hear the last voices of World War II).

“My view is that this type of object is incredibly important in providing us with markers of our own history,” Wilson says. As the living tellers of these stories pass away, these objects, places and their photographic documents become ever more important—to provide that key to the human past of a land.”

This story was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.