Satellites spotted 76 strange stone structures in the Andes. Scientists now know what they are.

An archaeologist is piecing together what the V-shaped stone structures—some stretching 500 feet long—were used for.

From a vantage point high above the Andes, Adrián Oyaneder spotted the ancient campsites first—and later the 76 stone wall structures, scattered in strange formations across the mountain landscape.

Oyaneder, who grew up in Chile, is an archaeologist at the University of Exeter in England focusing on ancient South American civilizations. He was poring over satellite photographs of a remote mountain valley in northern Chile called the Camarones River Basin. But he couldn't explain what he was looking at.

"I was finding loads of walls at the beginning, really long walls," Oyaneder says. "I started questioning if I needed new glasses or a new computer."

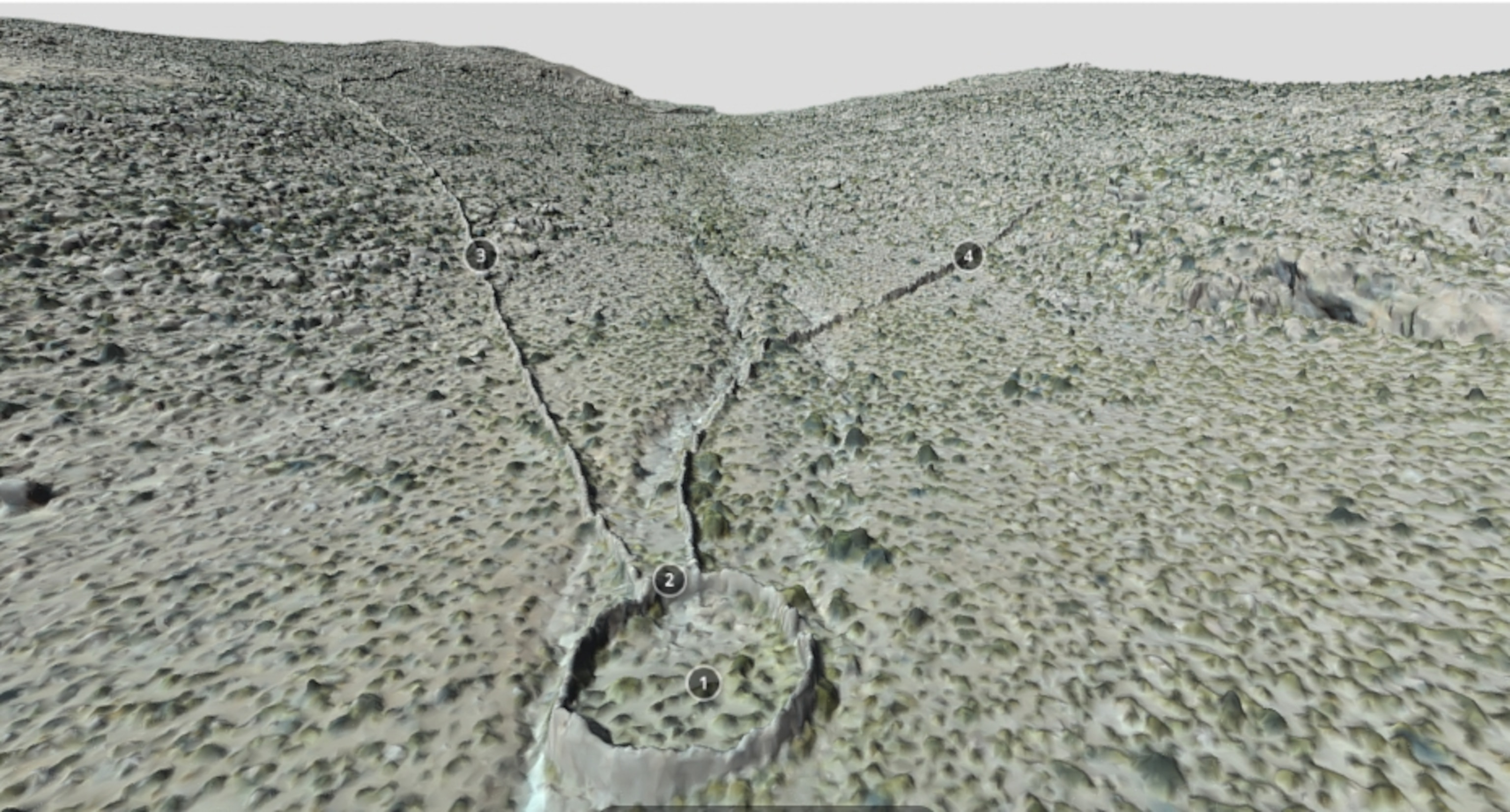

The long stone walls—many measuring around 500 feet long and about five feet high—were all built on steep mountain slopes. They were often arranged in pairs that converged into a “V” and emptied into circular, stone enclosures.

But when Oyaneder hiked out to some of the structures to get a closer glimpse, he found that even the local people living nearby were unsure what they were called or why they were there. They referred to them as "trampas para burros" or donkey traps, says Oyaneder. That was a clue.

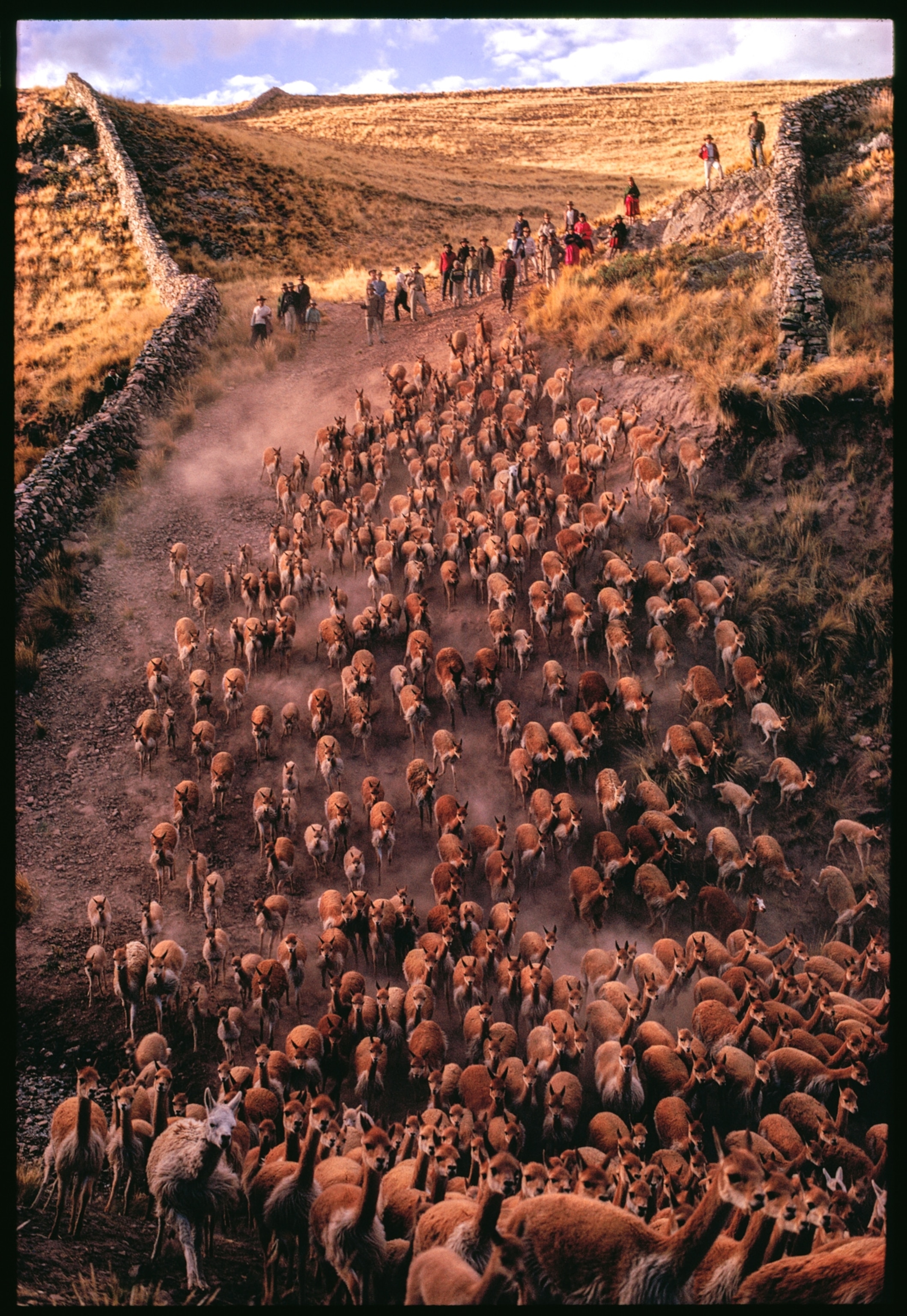

To further investigate, Oyaneder next turned to scattered archaeological reports, many of them from 20th century Peru, for more insight. Only then did he realize what the structures were. The texts from Peru told of large stone structures called chacu that were once used by the ancient Inca in "royal hunts" to trap vicuñas, furry animals that look like little llamas.

In a study published this week in Antiquity, Oyaneder suggests the Chilean stone structures he found are ancient animal traps, similar to the ones found in Peru. He says that some of these mega traps may date back about 6,000 years, and some were used by hunters as recently as a few hundred years ago.

It seems that these newly discovered chacu, too, were used to trap vicuñas, which were once abundant in the area but were hunted almost to extinction after the Spanish arrived, Oyaneder says. Ancient rock art from the Andes also depicts vicuñas being funneled into chacu—and he notes that the traps are all built at high altitudes, typically over 9,000 feet above sea-level, where wild herds of vicuñas once roamed.

(Ancient cave art may depict the world's oldest hunting scene)

Oyaneder has also identified traces of almost 800 nearby stone shelters and campsites that likely housed the hunters, indicating this way of hunting was much more common than archaeologists thought. His discovery has revealed a new part of the world where these sorts of traps for wild herds were widespread, and it suggests that other parts of the Andes might also contain such ruins.

Stone traps beyond the Andes

The new study is also interesting because archaeologists have found almost identical ancient traps elsewhere in the world in places that have had no contact with ancient South America.

The structures, sometimes called “desert kites” because of their shapes, have been documented in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Uzbekistan, and some are thousands of years old. Evidence suggests they, too, were used to direct stampeding herds of wild animals—usually gazelles, but possibly wild camels—within the stone walls and funnel them into kill pits.

Oyaneder says the traps are examples of parallel development—what anthropologists call "convergence"—where different societies independently develop very similar technologies despite having no contact with each other.

"If you think about the shape of prehistoric fishhooks—you get similar solutions [in different places] depending on the type of fish that you want to catch," he explains. "The same happens with these traps. If you have highly elusive animals and a limited number of people, and you want to be selective or not put much effort into it, then this is the solution."

Oyaneder had been examining the satellite photos for evidence of prehistoric hunter-gatherer groups, but he was astonished by just how common chacu were in this region.

(Space archaeologist wants your help to fight looting)

His discovery establishes that such wild animal traps were once common in the Camarones River Basin and possibly in other mountainous parts of South America, although surviving evidence of them elsewhere is extremely rare. Until the latest study, "there wasn't physical evidence of more than a dozen of these traps in the whole of the Andes," he says.

David Kennedy, an archaeologist and professor emeritus at the University of Western Australia not involved in the study, says the new discovery is wonderful. "The kites in Chile are very similar to many I have photographed and mapped across the entire Middle East," he says. "The principle is simple and obvious, and I have seen [modern] examples of similar traps being used to cull kangaroos."

The hunt continues

The discovery also challenges ideas about the local transition from hunting to farming. Archaeologists thought most people in the Andes were herders or farmers by the time the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 1530s, and that hunting there had mostly died out almost a thousand years earlier. But Oyaneder's research suggests that wild hunts with chacu coexisted with farming and herding for hundreds of years after the Spanish Conquest.

Rémy Crassard, an archaeologist with the French national research agency CNRS, who was not involved in the study but who has studied desert kites in the Middle East and Central Asia, calls the work "solid and innovative" research.

"It convincingly shows how remote sensing can reveal large-scale hunting landscapes in the Andes," he says. Crassard cautioned, however, that there is still much to be learned about the chacu in Chile. "More excavation will be needed before drawing firm chronological conclusions."

(Where should archaeologists dig next? The winners of this OpenAI contest can tell them.)

Oyaneder plans to train a machine-learning system to scour satellite images for traces of chacu in other Andean mountain valleys. He will continue his research on foot in the Camarones River Basin.

But it can be rough work.

"Usually, I go on Google Earth and look for nearby roads, or things that look like roads," he says. "And sometimes it rains so much that roads disappear."

So far, Oyaneder has hiked to about 10 of the newfound chacu and documented them with three-dimensional photogrammetry. He has also carried out excavations at four sites, in search of evidence of the animals that were trapped there. The excavations have not yet yielded new insights, but still he hunts for clues.

"The landscape is really rugged,” he says, “so to get from one point to another is quite difficult and takes a lot of planning—it's the Andes."