6 archaeological discoveries that amazed the world in 2025

Modern tools and good old-fashioned digging revealed royal tombs, World War II shipwrecks, and the oldest Egyptian genome ever sequenced.

Cutting-edge scientific tools reshaped archaeology this year: Ancient DNA sequencing reconstructed the ancestry of an Egyptian who lived at the dawn of the pyramids. Satellite images captured traces of massive ancient hunting traps strewn across the Andes. And underwater mapping brought sunken World War II warships back into view and uncovered a submerged port that may hold clues to finding Cleopatra’s final resting place.

But many of 2025’s biggest discoveries also came from classic excavations. In Belize, a dig at a pyramid at Caracol unearthed a chamber containing a royal Maya burial. Near Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, archaeologists unearthed the last missing tomb of an 18th-Dynasty pharaoh.

Taken together, they hint at how much human history still lies hidden—in deep waters, dense jungles, and desert sands—waiting to be found. Here are some of the most interesting and exciting findings in archaeology from 2025.

1. A royal tomb in Belize may belong to the founding Maya king of Caracol

For nearly 40 years, archaeologists Arlen and Diane Chase from the University of Houston have excavated the ancient Maya structures of Caracol in the jungles of modern-day Belize. This year they announced one of their biggest finds yet: a 1,700-year-old royal tomb dating roughly to A.D. 330-350. They believe it belonged to a renowned ruler, Te K’ab Chaak.

Inside the cinnabar-covered tomb, the researchers found a shattered mosaic death mask made of jade and shells, jade ear flares, and the bones of an elderly man whose skull had rolled into a pottery vessel. If their hunch is right, and the remains do belong to Te K’ab Chaak, that would mean they’ve discovered the founder of a Maya dynasty that ruled the city for nearly 500 years. The findings at the site—specifically, a cremation burial and green obsidian blades—also offer clues to a possible relationship between the Maya living there at the time and the faraway but powerful city of Teotihuacan.

(Stunning jade mask found inside the tomb of a mysterious Maya king)

2. The search for Cleopatra discovers a sunken port off the Egyptian coast

From the rise of a Maya dynasty to the fall of Egypt’s Ptolemaic kingdom: this year, archaeologists also made a discovery that may help locate Queen Cleopatra’s tomb. For two decades, National Geographic Explorer Kathleen Martínez has searched for Cleopatra’s final resting place—not in Alexandria, where most scholars believe she is buried, but in a little-known temple nearby called Taposiris Magna. Her search has led her to the Mediterranean Sea where she and her team found a submerged port that dates to the queen’s era.

(Learn more about Kathleen Martínez and her search for Cleopatra)

Divers led by National Geographic Explorer at Large Bob Ballard mapped polished floors, towering columns, and anchors beneath the waves. The finding, which was featured in the National Geographic documentary Cleopatra’s Final Secret, reframes Taposiris Magna as an important maritime hub as well as a religious center. That finding, Martinez says, strengthens the case that Cleopatra chose the location for her tomb. Whether her remains lie somewhere offshore is a question only further exploration can answer.

3. WWII shipwrecks reveal insight into the deadly Guadalcanal campaign

In addition to his work looking for Cleopatra, Ballard also led a deep-sea expedition to Iron Bottom Sound in the Solomon Islands in July to explore sunken World War II ships. The seafloor there is a solemn graveyard for the more than a hundred Allied and Japanese vessels destroyed during the Battle of Guadalcanal. Some have not been seen since the 1940s. During this expedition, Ballard and his team aboard the E/V Nautilus used ROVs to survey 13 wrecks, including the Imperial Japanese Navy destroyer Teruzuki and the shattered bow of the U.S.S. New Orleans.

The team also revisited the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra, sunk during the catastrophic Battle of Savo Island, and examined the collapsing remains of the U.S.S. DeHaven, one of the last ships lost in the Guadalcanal campaign. The explorations highlight both the tactical history of the Pacific War and the human cost: more than 27,000 lives were lost in the six-month struggle for Guadalcanal.

4. The lost tomb of pharaoh Thutmose II is found

Though the search for Cleopatra continues, a different Egyptian ruler was finally found this year. The tomb of King Thutmose II eluded archaeologists for more than a century before a combined British and Egyptian team announced discovering it this past February. Thutmose II, whose wife and half-sister was the famous queen (and, later, pharaoh in her own right) Hatshepsut, ruled from 1493 to 1479 B.C., during the early 18th Dynasty.

It is the first royal tomb since King Tutankhamun to be found near the famed Valley of the Kings, which is located close to Luxor. Inside, archaeologists came across walls inscribed with hieroglyphics and a painted celestial ceiling.

5. A closer look at Andean megastructures rewrites ancient mountain life

Across the Andes, humans engineered entire landscapes to coordinate trade, calculate tributes, and capture elusive prey. In Peru, researchers may have finally solved the mystery of a massive “Band of Holes” dotting a remote mountainside called Monte Sierpe, or "Serpent Mountain." They think that the 5,000-some holes were used as a marketplace and accounting system by Chincha peoples and later expanded by the Inca. Aerial photographs of the holes were featured in a 1933 issue of National Geographic. More recently, researchers have used drones to see the holes from above. The drone mapping and analysis of plant remains suggest the pits once held baskets of goods and that they may be connected to an ancient counting method seen in knotted strings called "khipus."

(Where should archaeologists dig next? The winners of this OpenAI contest can tell them.)

Far to the south in Chile’s Camarones River Basin, satellite images led an archaeologist to 76 V-shaped stone structures believed to be “chacu,” large hunting traps. The ancient people who lived there used the 500-feet long stone walls to funnel wild vicuñas, little llama-like animals, into circular corrals to be slaughtered. The two discoveries illustrate how ancient Andean societies shaped the land for generations to meet their needs.

6. The oldest and most complete ancient Egyptian genome ever sequenced

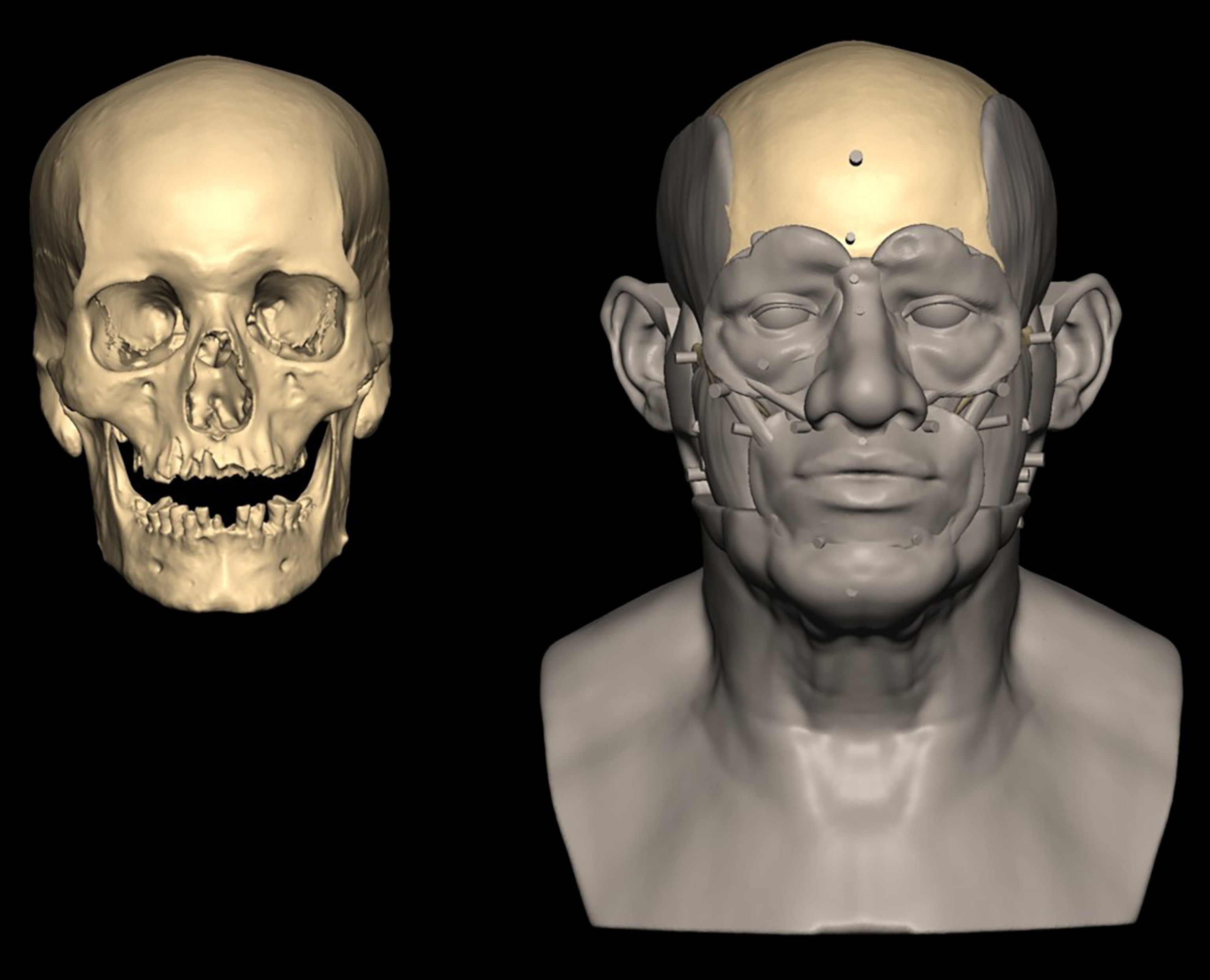

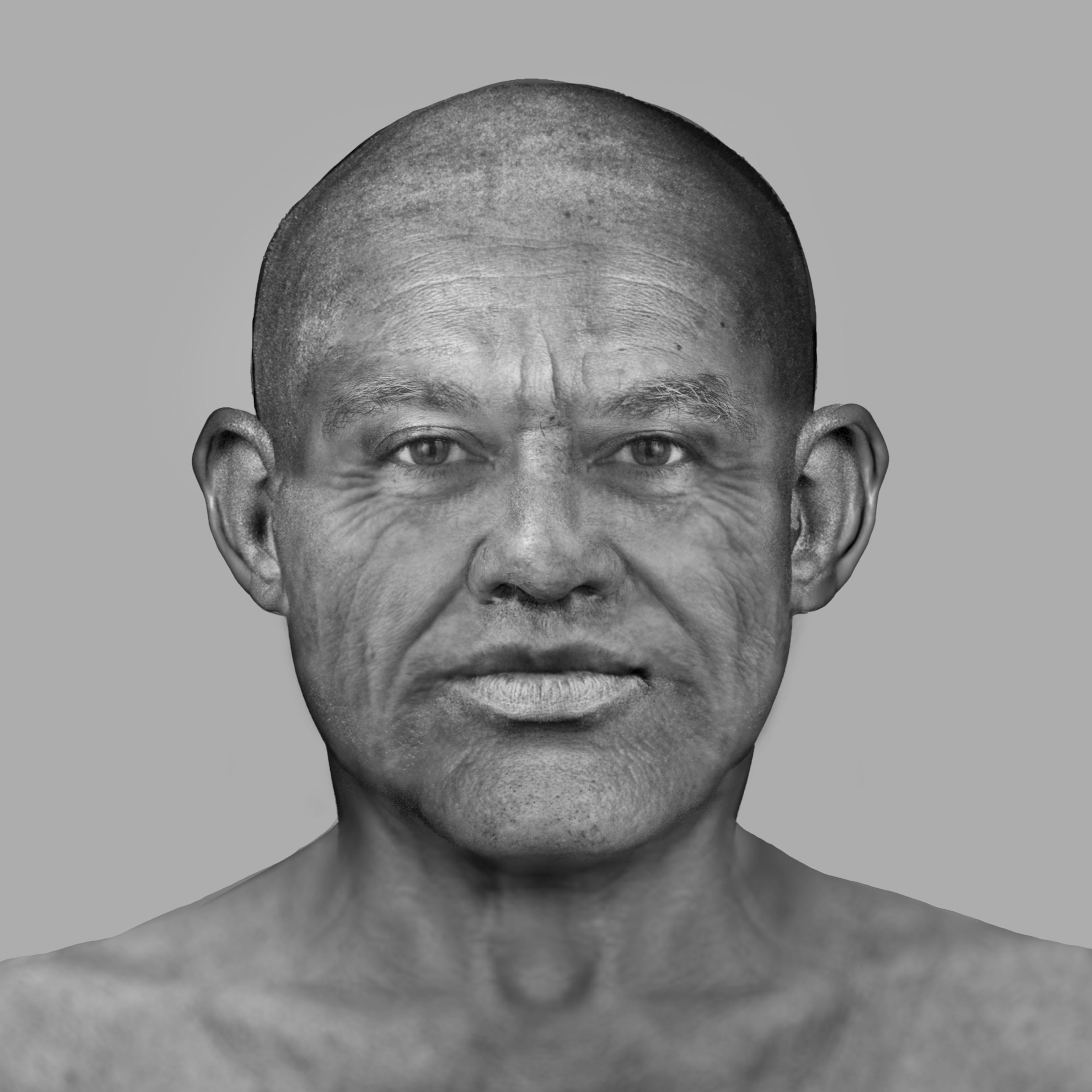

Within a tomb cut into a limestone hill at the Nuwyat necropolis in Egypt, archaeologists found a ceramic pot. Curled inside it was the skeleton of a man from the Old Kingdom Period, some 4,500 years ago. And inside one of that man’s teeth, scientists recovered a genetic time capsule that offers the earliest and most complete glimpse yet into the ancestry of an ancient Egyptian.

The analysis showed that 80 percent of the man’s DNA came from Neolithic North African groups, and 20 percent from populations located in West Asia. The scientists also used a 3D scan of the Nuwyat man’s face to reconstruct what he may have looked like (but leaving out hair and skin color, which they felt were more speculative). They stressed, though, that he was not representative of all people who lived up and down the Nile at that time.

As to why the man was buried in a pot, the researchers are unsure. But strains on his bones suggest he did a lot of repetitive, back-bending work, leading them to deduce that he was possibly a skilled potter (and likely not a pyramid builder).