The Suez Canal blockage detoured ships through an area notorious for shipwrecks

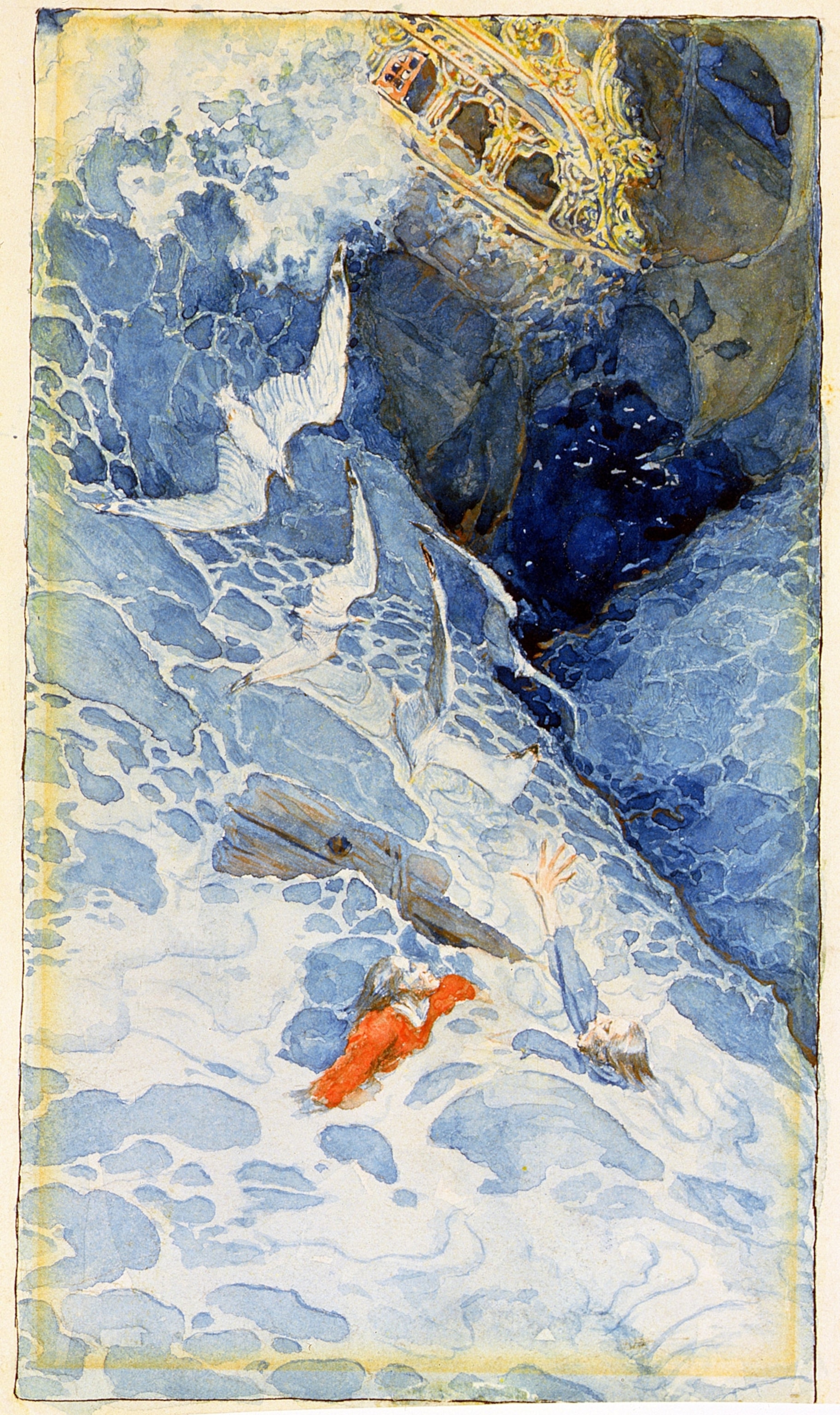

South Africa's Cape of Good Hope has claimed thousands of ships—and remains treacherous today.

By the time the Suez Canal was finally unblocked on Monday, a number of waiting ships had opted for plan B. Rather than risk further delay—in addition to the full week, at an estimated $400 million per hour collectively—some container vessels began to take the long route around South Africa.

The journey adds at least 10 days and thousands of miles depending on the destination. The southern route is also considerably more dangerous: Fierce winds, rocky outcrops, and heavy shipping traffic through history have made the Cape of Good Hope one of the world’s most treacherous ship graveyards.

“Over hundreds of years, the cape has been a hotspot for shipping accidents,” says Bruno Werz, a maritime archaeologist and head of the African Institute for Marine and Underwater Research based in Cape Town. “It's definitely more dangerous to go that way, so it’s a calculated risk.”

Werz and other researchers have conducted extensive studies on maritime accidents in the waters off Southern Africa and estimate there are at least 2,000 wrecks in South African waters, an average of one for every kilometer of coastline. Many are relics from eras of European exploration and ill-fated voyages to reach India and Asia.

One of the earliest recorded, known as the Soares wreck, was the first of hundreds of 16th-century Portuguese ships wrecked on South African rocks as it shuttled up and down the Atlantic and to eastern colonies. Another still studied today, the Haarlem, wrecked in South Africa’s Table Bay in 1647; an outpost set up by its survivors was the forerunner to the modern city of Cape Town.

The Cape of Storms

The region’s name is believed to have derived from its history of punishing conditions. In 1488, Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias attempted to reach India in on a journey that took him around Africa’s southern point. According to a story in which myth and fact have become inseparable, when Dias returned to Portugal to report to King John II, he said that conditions around the cape were so intense he called it the Cabo das Tormentas, or Cape of Storms.

King John, who hadn’t been aboard Dias’ wind-tossed ship, was so elated by Dias’ larger finding that he ordered it be called the Cape of Good Hope because it offered a hopeful prospect of reaching markets in India.

Thousands of shipping captains would probably side with Dias. In the modern era, statistics show that ships founder at higher rates around the cape than in many stretches of open ocean. In 1911, a year before the Titanic sank in the Atlantic, the passenger liner the SS Lusitania (a ship different from the RMS Lusitania that sank near Ireland) mistook the Cape Town lighthouse for the southernmost point of the continent, turned too steeply, and struck land. In the years before, dozens of other ships also misread the coast—a phenomenon that led to the lighthouse being moved further south.

In 1942, the American troopship the SS Thomas Tucker ran aground off Cape Point during its maiden voyage and washed up on land in an area now known as the Shipwreck Trail. In 1965, after a Dutch ship carrying whiskey wrecked, its captain famously steered the ship to shore to save its cargo. As recently as 1994, a giant French barge carrying a crane broke its tow and drifted onto rocks. It was too big to save and was abandoned.

The Roaring Forties

The ferocious weather around the Cape peninsula comes from a southern stream of air that blows around the entire circumference of the earth beginning at the latitude of 40 degrees south. Unimpeded by almost any landmass so far south, the wind gives the region its centuries-old nickname, the “Roaring Forties.” And it gets worse as ships go further south into the “Furious Fifties” and the “Screaming Sixties.”

Throughout history, the wind has been a boon or a burden to sailors depending upon which way they were going. Intense wind could push ships eastward across the Pacific, for example, at breakneck speed. But going the opposite way could take weeks, sometimes months. And after a lengthy journey on the open ocean, a sudden landmass like the Cape of Good Hope—or Cape Horn in South America—could make the wind behave erratically and push ships quickly off course.

Modern container ships

Many fewer ships sink today around the Cape of Good Hope than in centuries past. When it was completed in 1869, the Suez Canal offered a safer, shorter, and less expensive route for the world’s biggest ships or those carrying the most valuable cargo.

In general, there’s far less risk-taking on dangerous waters thanks to a combination of factors: GPS navigation, weather forecasting, automated anchoring, and—on some vessels—a system known as dynamic positioning that uses synchronized motors to keep a ship from drifting.

But shipwrecks still occur, some in cases of human error or unexpected weather. In 2003, a cargo ship called the Sealand Express was carrying 33 containers—a tiny fraction of the load of today’s larger vessels that can carry more than 10,000. The cargo ship ran aground on a sandbank near Cape Town after it dragged its anchor in gale-force winds, an incident blamed on a slow-to-react crew. That accident occurred in August toward the end of the Southern Hemisphere’s winter that brings exceptionally high winds. The windy season begins in March.

Daniel Stone is a contributing editor for National Geographic. His next book, SINKABLE, about the fascinating world of shipwrecks and the hunt for the most famous one, will be released in 2022.