The archaeological treasures that survived 9/11

Nearly a million artifacts spanning four centuries of New York history were stored at the World Trade Center. These are the stories they told.

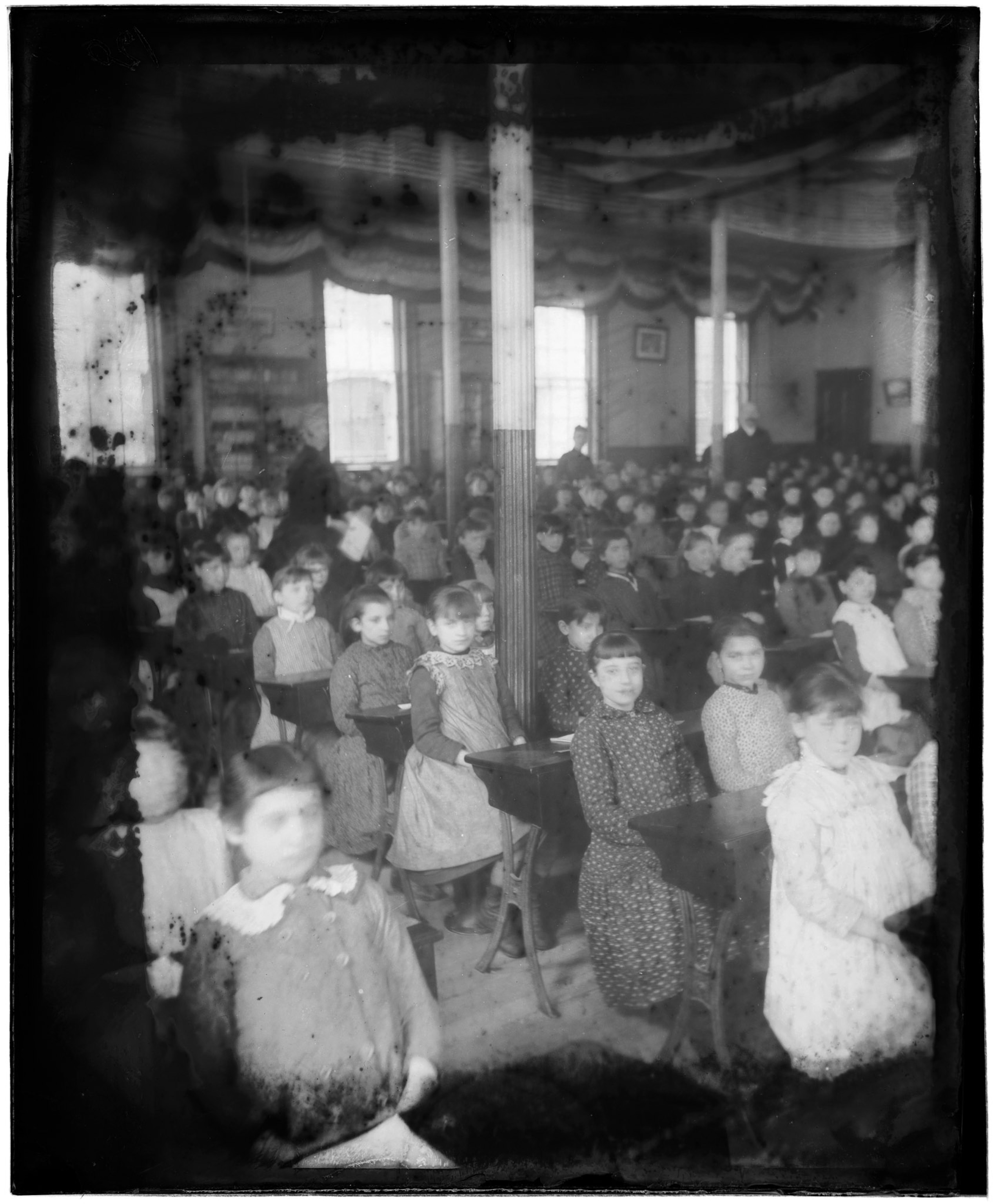

In 1992, urban archaeologist Sherrill Wilson was scouting for space for a lab and research center in the World Trade Center, and an office manager had suggested the 67th floor of the North Tower. Wilson shuddered, recalling a haunting memory from a few years before when she’d seen people jumping from a window to escape a fire. She also knew that a group of Boy Scouts had recently been stuck in a WTC elevator for a few hours. As the head of public information for the New York African Burial Ground project—a recently unearthed graveyard of thousands of freed and enslaved Africans—Wilson often welcomed schoolchildren to her office to learn about the evolution of New York City.

For these and other reasons, she refused to even visit the 67th floor. “I said, ‘I’m a single mother and have three kids and they’re expecting me to come home at the end of the day.’” Instead, the African Burial Ground project took over part of the ground floor and basement of Six World Trade, an eight-story building next door that held a number of federal offices. A year later, in 1993, Wilson felt the floor of her lab shake from a bombing attempt on the World Trade Center. Eight years after that, the façade of the North Tower fell into Six World Trade and destroyed thousands of historic artifacts.

Nearly 3,000 people died on the morning of September 11, 2001, when two planes struck the Twin Towers in lower Manhattan. In the weeks and months after, historians would try to take stock of the hundreds of thousands of historical items also missing amid the debris. These artifacts told the origin story of New York and the history of the enslaved men and women and immigrant workers who built the city into a global powerhouse.

A harrowing history unearthed

From her years as a professor and tour guide, Wilson knew that most people believed the Black presence in New York began with a post-Civil War migration. The discovery of the African Burial Ground in 1991, during the construction of a federal office building near City Hall, proved otherwise. Along with evidence of a large early African community, it revealed a brutal picture of slavery in which young, expendable laborers were needed to build an industrial city.

(Discover how artifacts pulled from the rubble of 9/11 become symbols of what was lost.)

In the early 1600s, Dutch colonists gave a swampy, six-acre plot on the southern end of Manhattan island to freed Africans to bury their dead, often under cover of night, as no more than four enslaved people were allowed to congregate together by law. Over 150 years, some 15,000 free and enslaved Africans were buried in an area slightly larger than the average city block. Today it sits under Manhattan’s financial district.

The bones from the burial ground told a harrowing story of the conditions for enslaved men and women. Researchers found that in just one generation, distinctive African traditions such as shaved teeth and ornate jewelry had all but disappeared. Bones bore physical evidence of difficult, dangerous work, including skull fractures from heavy loads dropped on enslaved dockworkers. The average lifespan was between 24 and 26 years.

Over the course of the decade-long study, finds from the African Burial Ground were processed in Wilson’s lab in the basement of Six World Trade. After documentation and analysis, the artifacts, soil samples, and coffin fragments were boxed and stored in the building’s basement. Human remains were sent to Howard University in Washington D.C. for further analysis.

A ‘Nest of Vipers’ redeemed

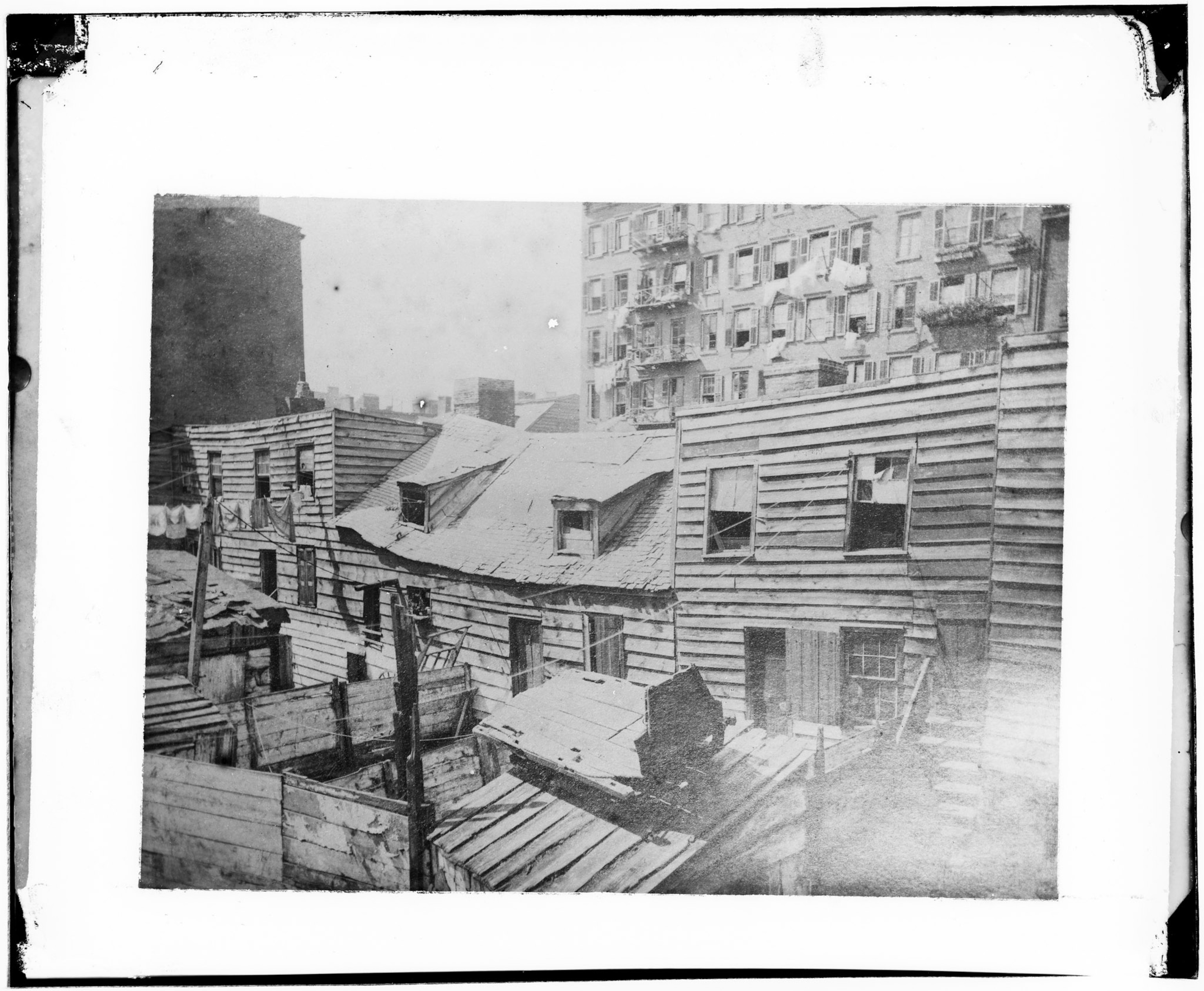

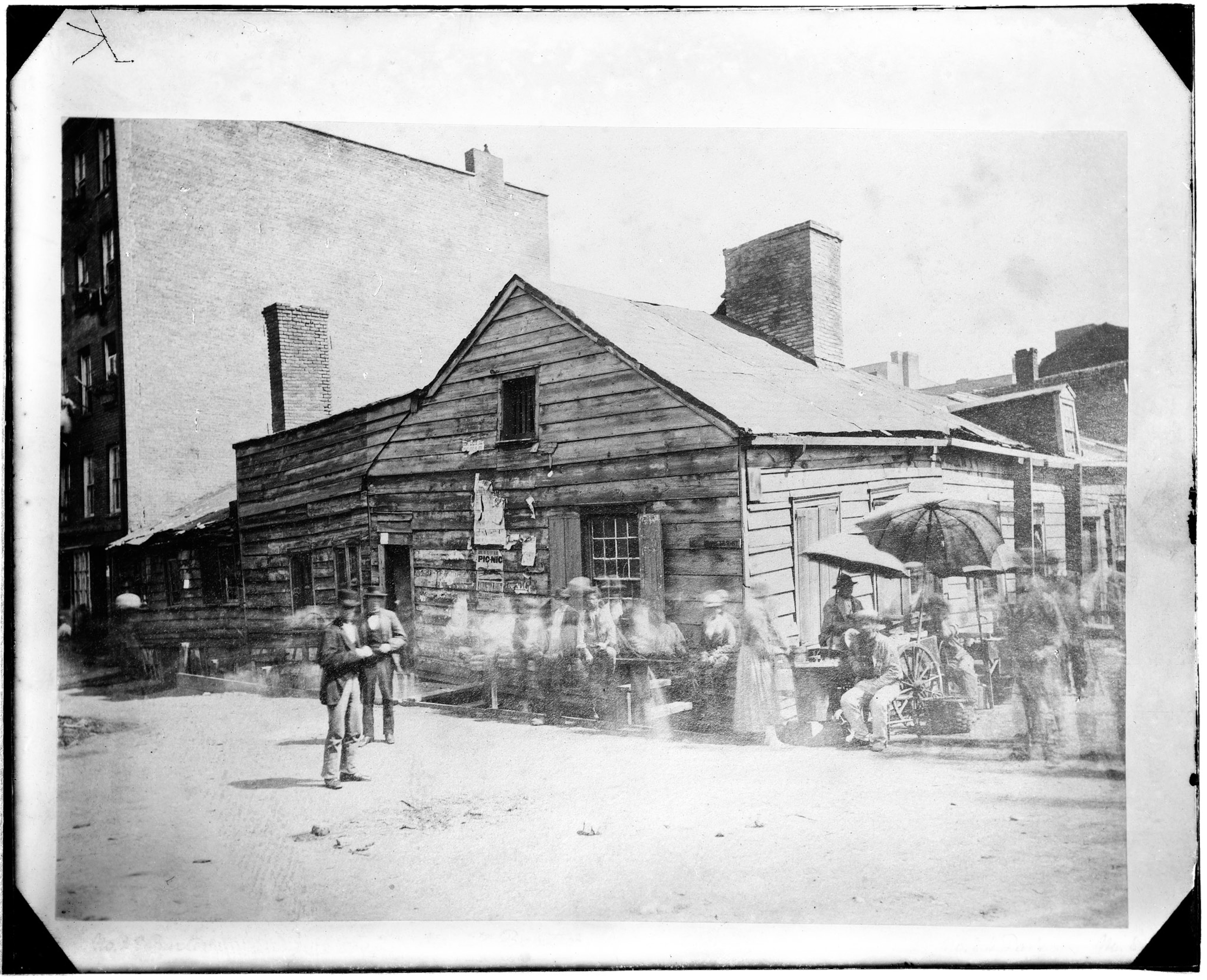

In 1991, the same year that the African Burial Ground emerged from a construction site, another archaeological discovery was being made at the nearby site of a planned federal courthouse. Beneath a parking lot, researchers came across the remains of Five Points, once one of the world’s most densely populated neighborhoods and 19th-century Manhattan’s most notorious slum.

(Read how seven National Geographic photographers covered 9/11.)

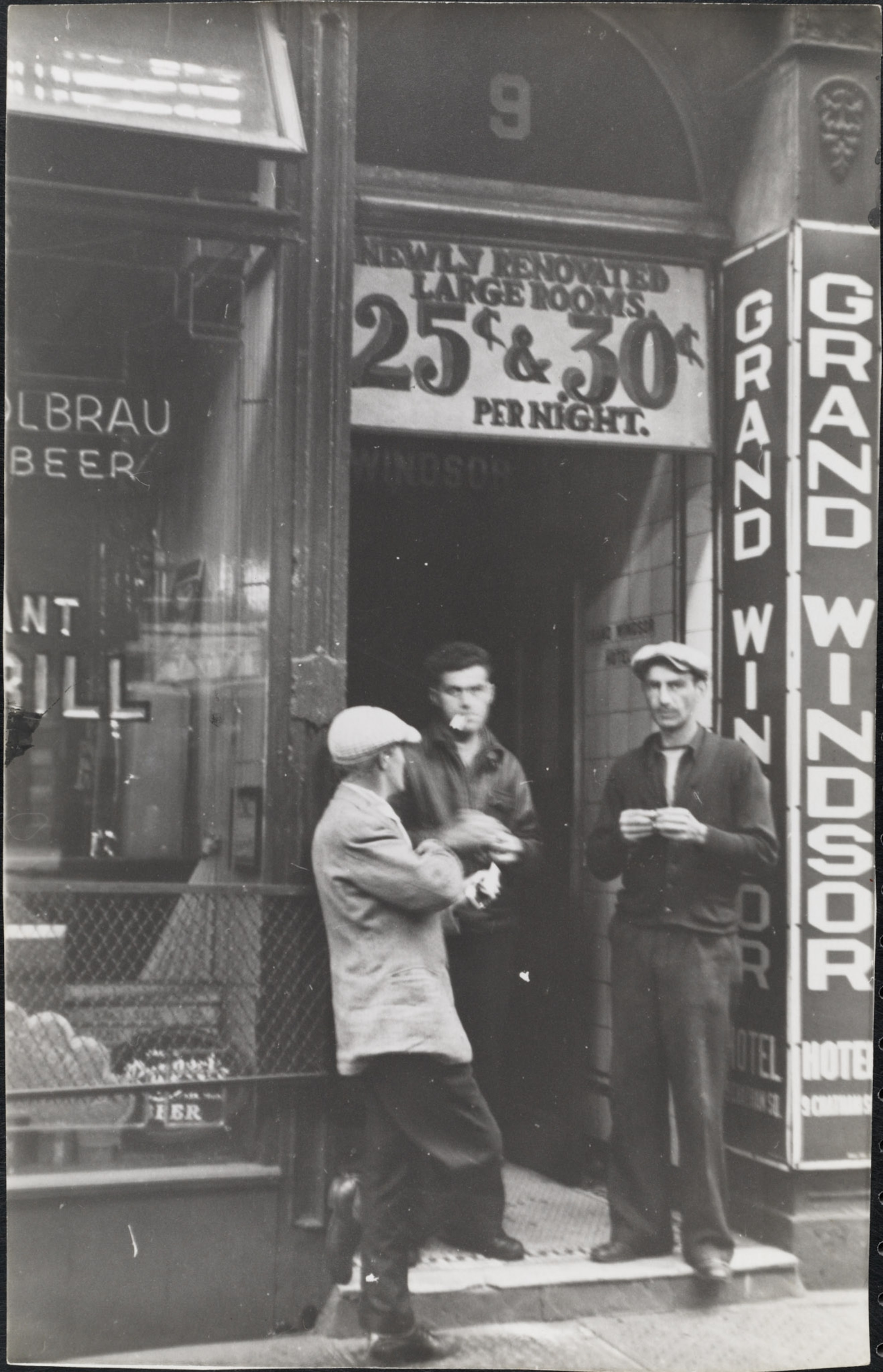

In the popular imagination, Five Points was infamous long before Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York. Newspapers in the mid-1800s dubbed it a “nest of vipers.” Visitors like Charles Dickens described the neighborhood of German and Irish immigrants as a hotbed of crime, violence, and prostitution. To well-heeled New Yorkers, the neighborhood was a cautionary tale of urbanism and justification for their disdain of immigrants and the working class.

The wealthy often fill the historical record with their own artifacts and perspectives, while the legacies of working classes are rarely preserved. But the Five Points site—which included the remains of 14 diverse properties, from a rabbi’s home to a brothel—yielded more than 850,000 working-class artifacts. To archaeologists, the staggering collection of everyday items such as soda bottles, tea sets, thimbles, and inkwells was a nearly miraculous find in a city constantly being torn down and rebuilt.

The Five Points artifacts joined the African Burial Ground project in the basement laboratory of Six World Trade, where the city provided space and funding for analysis. In an open gymnasium divided into cubicles and long tables, the lurid stereotype of Five Points got a reality check. The objects archaeologists cataloged painted a very different picture of life than the one presented in 19th-century tabloids. From the hundreds and thousands of artifacts recovered from the slum—scraps of cloth from home businesses, ornamental hair combs, tea cups with messages urging little boys to be good—a picture emerged of newly arrived families trying to dig themselves out of poverty.

“What does it mean that these people, who were supposed to be down-and-out criminals, were setting their tables with matching dishes and supplying children with toys just like the middle class?” asks historical archaeologist Rebecca Yamin, who directed the Five Points project. “The people who lived at Five Points had been misinterpreted by middle class observers and exploited for the excitement they represented.”

After five years of cleaning, analyzing, and documenting, archaeologists packed the hundreds of thousands of artifacts from Five Points into storage in the basement of Six World Trade to await a future permanent exhibit in the Seaport Museum on Manhattan’s waterfront.

Vanished history

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Sherrill Wilson was on a commuter train into the city when the conductor announced that two planes had hit the World Trade Center. Within hours thousands of New Yorkers were dead and untold pieces of history had vanished, including the archives of Helen Keller, the records of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and artwork by Picasso and Rodin that graced the walls of the city’s mightiest financial firms.

(See indelible photos that mark one of America's darkest days.)

Wilson made her way back home and learned that, as the North Tower fell, wreckage tore into Six World Trade, leaving a smoking crater in the eight-story building. As she watched her office smolder on CNN, she was reassured knowing the human remains from the African Burial Ground were safe at Howard University in D.C. But the fate of everything that remained in storage at Six World Trade—the burial ground artifacts and accompanying research library, as well as the Five Points artifact collection—was unknown.

A month later, in early November, city workers arrived at the remains of Six World Trade to salvage what they could. Among the items extracted from the wreckage was the nearly complete collection of artifacts from the African Burial Ground, stored in about a hundred boxes. An additional 200 boxes were recovered from the Five Points collection, but they contained only paper records of each artifact. The objects themselves were destroyed.

Rebecca Yamin was neither surprised nor upset that 850,000 shards of “slum” life that she and others had so carefully unearthed were gone forever, considering the human cost.

“We have to remember that September 11 really did eclipse a record of that part of the city,” she says. “The record of the past being lost is always a tragedy. It’s not the same as the tragedy of human lives. But it’s a loss of understanding of ourselves and where we came from.”

“You wouldn’t think that in a city like New York there’d be anything buried undisturbed,” the archaeologist adds. “Things can stay preserved in the ground for a long time and then in a moment they can be blown up.”

.jpg)

A final resting place

In lower Manhattan, a granite monument sits in the shade of towering skyscrapers. To one side, seven burial mounds rise up from a grassy field. Below them are the human skeletal remains from the African Burial Ground.

The bones were reinterred in their original resting site in Manhattan in 2003, following their analysis at Howard University. The contents of the roughly 100 boxes recovered from Six World Trade after the attacks—soil samples, coffin pieces, and other artifacts—were also eventually brought to Howard University’s W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory, where they are still being studied today, 30 years after their discovery and 20 years after they withstood the World Trade Center destruction.

Carter Clinton, a National Geographic Explorer, is currently looking at the burial ground soil samples to reconstruct the gut bacteria, or human microbiome, of the people who were buried some 400 years ago.

Even more than the skeletal remains—which can reveal age, gender, and physical maladies like broken bones—the human microbiome can reveal a nuanced picture of who was buried there, including their diet (mostly vegetables), environment (toxic waste from nearby pottery factories), and health (gastroenteritis, salmonella, and respiratory diseases).

“Once we exhaust these remains and samples, that’s all we have,” says Clinton. “It’s our last hope of figuring out what was going on in New York with these people at this time. We don't have names for these individuals, but we can still give them some form of identity.”

Clinton, who is African American and grew up in New York City, feels a duty to pull that information from the remaining evidence. “I wish the knowledge about the African Burial Ground was as vast as September 11th,” he says. “The reason that September 11 is so important is because of the people who built this city. When I think of the World Trade Center and New York Stock Exchange, I think of how they got started.”

Slavery in New York ended in 1827, but before that enslaved Africans expanded a small path used by Native Americans into Broadway and built the walls next to what became Wall Street. At the time, the value of their labor was estimated to be worth more than all the railroads and factories in the country combined. Their presumed worth was what American financial institutions built the Stock Exchange on.

“It was the Africans who made New York City New York City,” says Fatimah Jackson, who directs the Cobb Laboratory. “If we’d lost this material, it would have magnified the tragedy of 9/11.”

Jackson points out that despite genetic analysis, no single descendant community has ever been identified from the remains of 419 men, women, and children recovered from the African Burial Ground. “It just seemed the individuals in the burial ground, because of its early age and extensiveness, were related to just about all legacy African Americans,” she says. “If 9/11 had destroyed that, 40 million people would have felt yet another irretrievable loss.”

New York’s “triple survivors”

It wasn’t until a few months after 9/11 that Rebecca Yamin realized that not all the artifacts from Five Points were lost on that terrible day. By a stroke of luck, the archdiocese of New York had asked in 2000 to borrow a few pieces for an exhibit on early Irish history in New York. Yamin’s lab lent them 18 of their most precious artifacts: children’s marbles, tobacco pipes with finely carved designs, and the most prized of all—a delicate teacup painted with the image of Father Matthew, an Irish priest who preached temperance. At a time when Five Points residents were considered drunks and criminals, someone had carefully displayed this cup in their home.

The archdiocese returned the 18 artifacts in August 2001, and Yamin made the fortuitous call to have them sent straight to the Seaport Museum rather than returned to storage in Six World Trade. Today, they reside in the Museum of the City of New York, 100 blocks from their original home. A selection is on display in the museum’s permanent exhibit about the diversity of New York City at a time when German, Irish, and Jewish migration changed the city’s makeup. The prized teacup bearing the image of Father Matthew sits prominently in a glass case along the museum’s wall.

Chief curator Sarah Henry calls the Five Points artifacts “triple survivors.” They outlasted the slum, withstood being discarded and buried, and narrowly escaped destruction on September 11th.

Henry was at a museum board meeting at the Tweed Courthouse just northeast of the World Trade Center on the morning of September 11th. A booming sound reverberated through the building as the first plane plowed into the North Tower.

“I think every historian feels that gut wrenching feeling, especially after all those years of work and excavation and bringing forth of knowledge that had been hidden, only to have it disappear a decade later,” says Henry. “I don't want to make any kind of equivalence, but it did feel very poignant. It was another blow.”

A few weeks later, the city’s museum curators gathered to discuss their role as institutions: What do they collect in the aftermath of such a disaster, and when? Soon they were awash in artifacts—missing persons posters, letters, memorial candles. They realized that New Yorkers were desperate for their experiences to be documented and preserved. Henry advised a group appointed by the Port Authority on what physical objects to salvage from the wreckage of the Trade Center and save for future generations to study, learn from, and reevaluate.

New York City had generated a new artifact collection, items that together could tell the story of a time of crisis and the individuals who died and those who lived. Today, the new and old artifacts sit separated by a hallway in the Museum of the City of New York. In one room pieces from Five Points illustrate the early city and the people who built it. In the other, remnants from September 11th bring the story of New York, one continually built and destroyed and run through with repeated threads of trauma and heroism, into the 21st century.