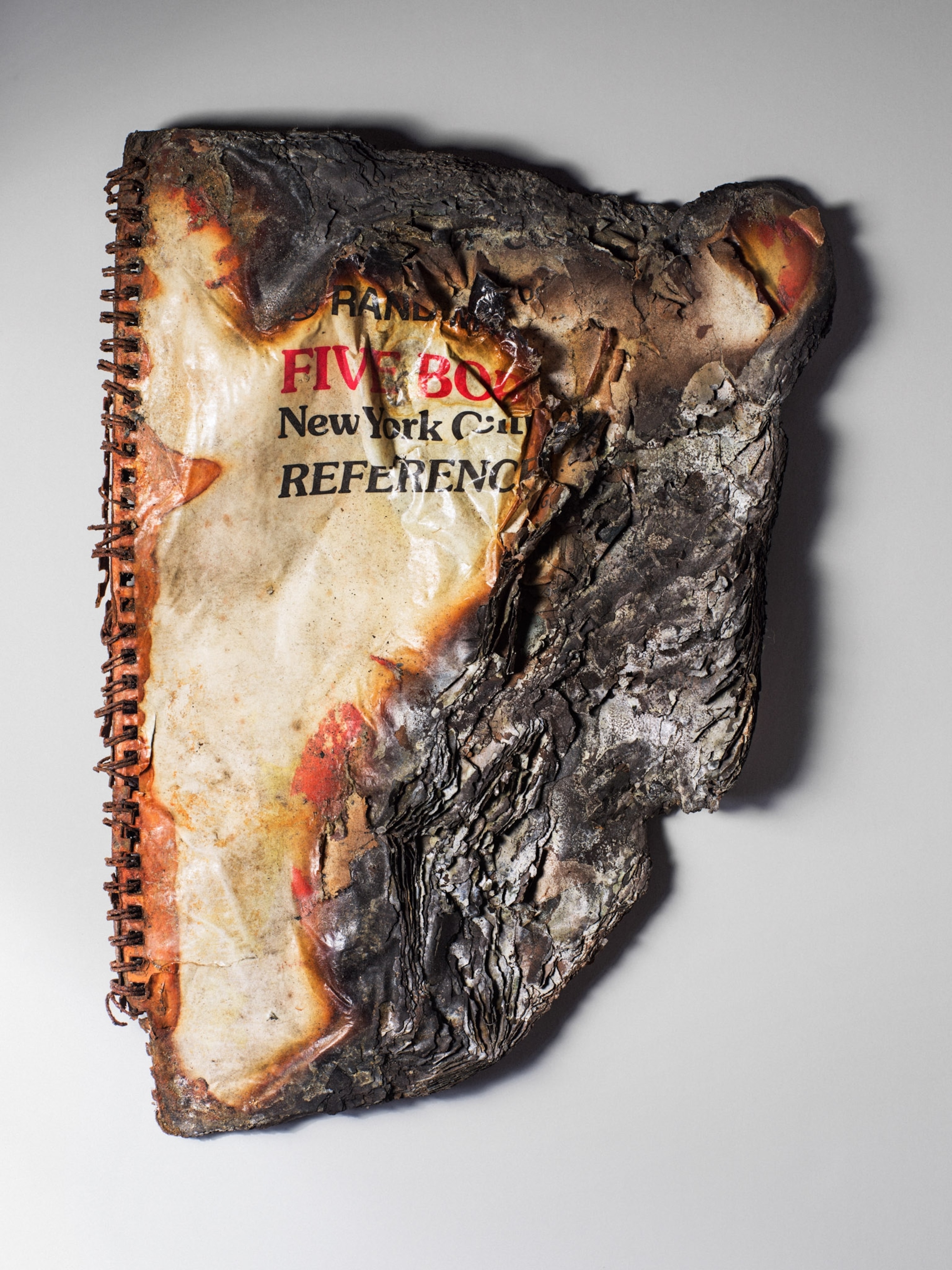

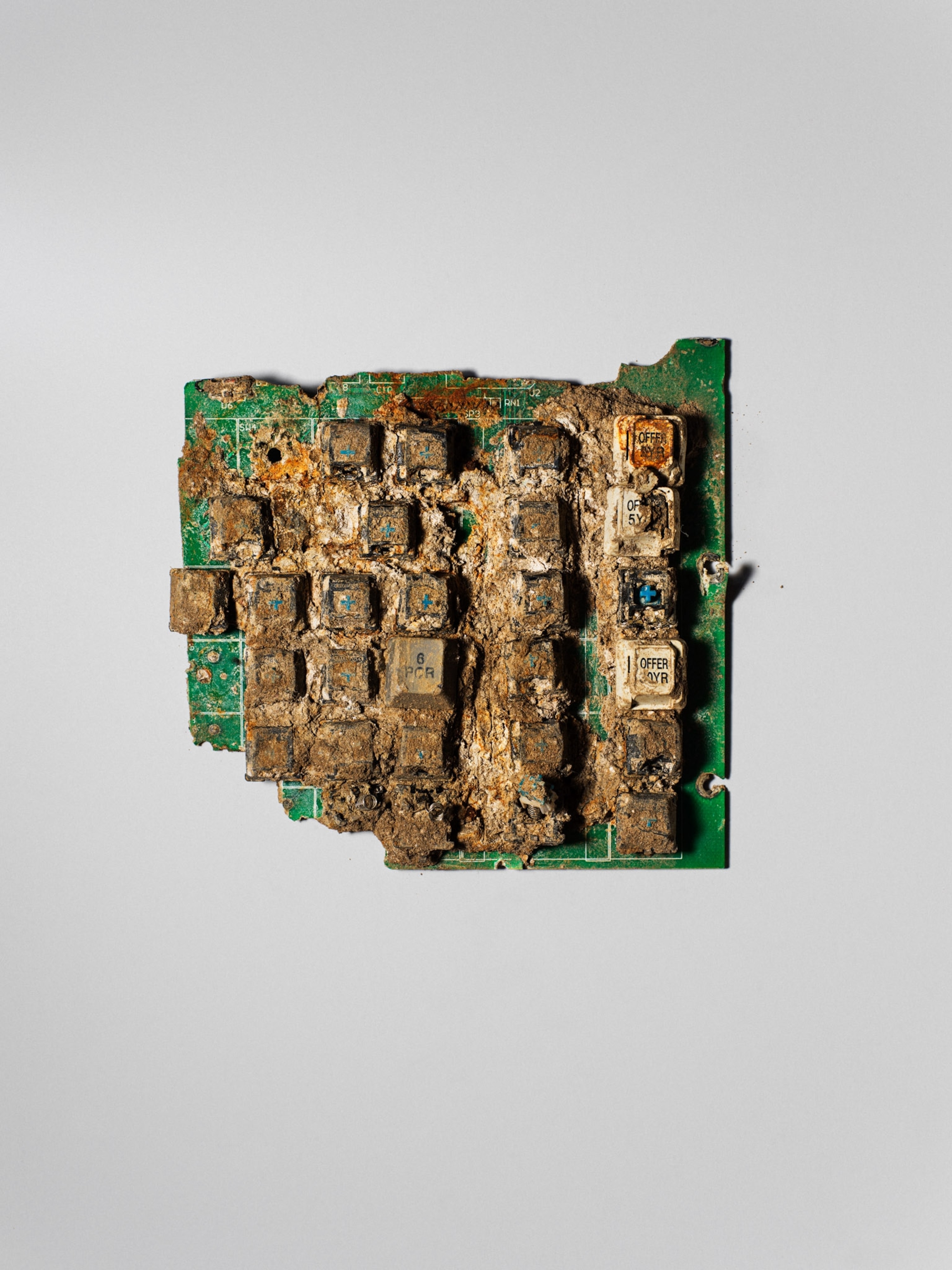

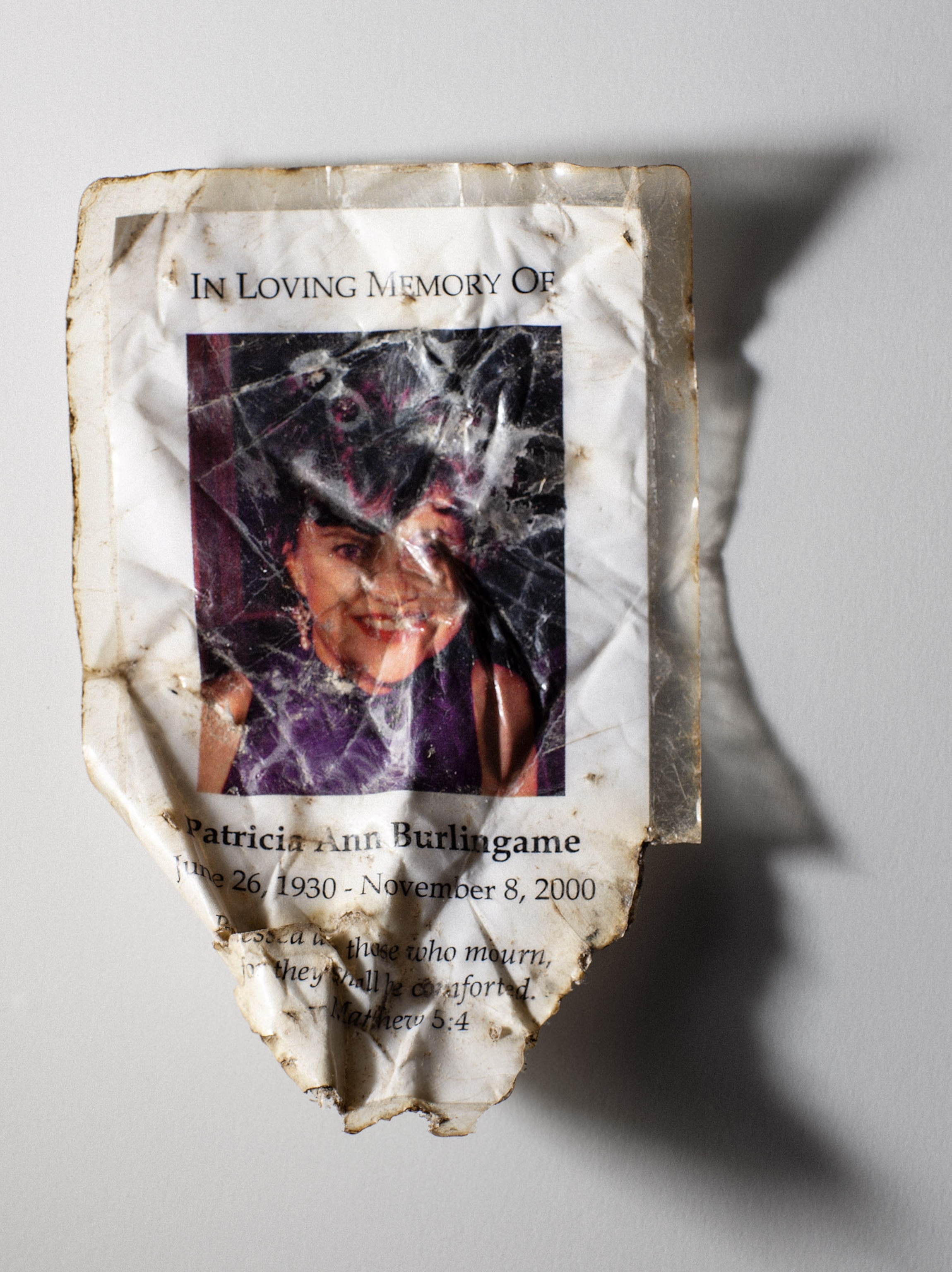

Artifacts pulled from the rubble of 9/11 become symbols of what was lost

Items left by victims of the attacks and those who tried to help them tell stories of bravery, loss, and perseverance.

What forces can sanctify an object, giving it meaning beyond itself? Selflessness. Courage. Endurance in the face of the unspeakable. The forces that Joe Hunter and hundreds of other people summoned on September 11, 2001.

Joe Hunter’s dreams rode on fire engines. At age four, he’d pedal his Big Wheel to the corner as the red trucks passed. At 11, he’d run fire rescue drills with a ladder and a garden hose, and if his pals didn’t take it seriously, he sent them home: “OK, you—out!”

He started as a volunteer fireman, graduated from the New York City Fire Department academy, took rescue training for terrorist attacks and building collapses. When his mother, Bridget, worried, he’d tell her, “If anything ever happens, just know I loved the job.”

Eighteen days shy of his 32nd birthday, Firefighter Joseph Gerard Hunter of FDNY Squad 288 died helping evacuate the World Trade Center’s south tower. He was one of 2,977 people killed on 9/11 when al Qaeda hijackers used passenger jets as weapons in the deadliest terrorist attack ever on U.S. soil.

In February 2002, searchers at ground zero recovered a Squad 288 helmet bearing Hunter’s badge number. “Of course, it’s mangled,” says Hunter’s sister, Teresa Hunter Labo. But the family is grateful it was found because “it’s the only thing we have of him that was down there, that was with him.”

In the two decades since 9/11, memorials have been built at the crash sites in New York City, at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, and in a field in Pennsylvania. Artifacts in each place reflect the particulars of each tragedy: When United Flight 93 crew and passengers tried to retake the plane, hijackers flew it into the ground near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, at more than 560 miles an hour. Other than one section of fuselage and two crumpled engine parts, most of what remained was in small pieces.

At the 9/11 Memorial & Museum in New York, more than 70,000 objects help tell the stories of victims, responders, and survivors. Artifacts are as small as a sapphire-and-diamond ring and as massive as a half-crushed fire engine. Many are utterly common: a food container lid, perhaps from a lunch packed on what started like any other Tuesday. But some common items’ poignance is in the details: The unfinished knitting, still on the needles, was the hobby of an executive at Cantor Fitzgerald—a company that lost 658 employees in the north tower.

In Joe Hunter’s memory, his family has donated his helmet to the museum: “It belongs there,” his sister says. It’s preserved with the other artifacts, common but uncommon, in silent witness to history.

Sacred Dust

Buried Alive

DEVOTION TO DUTY

Vow To Live

Tune in for National Geographic’s 5-part limited series 9/11: One Day in America streaming now on Hulu.

Patricia Edmonds, senior director for short-form content, oversees the magazine’s EXPLORE section. Henry Leutwyler is a Swiss photographer based in New York City; he was there on 9/11. Hicks Wogan contributed to this report.