Inside the elaborate world of Viking funerals

The great Norse warriors not only believed in the afterlife, but saw it as their duty to help the deceased get there, with complex ceremonies such as burying their dead in ships.

The first image that springs to mind when we think of Vikings may be that of an axe-raising, bearded raider, but behind all the blood and glory lies a culture still shrouded in mystery, especially when it comes to death.

For the Norse, the afterlife wasn’t a single, unified place. It was made up of distinct spiritual otherworlds. Some warriors slain in battle went to dwell in Valhalla, or Valhöll in Old Norse, known as “the hall of the slain.” Here, warriors fought and feasted endlessly while waiting to be called by the god Odin to Ragnarök, the catastrophic end of the world. Other warriors dwelled in Folkvangr, the “field of the army” ruled by the goddess Freyja. The most commonly portrayed afterlife was that of Hel, a cold and misty underworld ruled by a goddess of the same name. Unlike the Christian hell, Hel was not a place of punishment, but of stagnation. Viking beliefs were steeped in a fierce sense of wyrd, or fate, controlled by the Norns, three mythic weavers who spun the destinies of gods and humans.

These afterworlds were not always the final destination after death, since the Vikings believed the soul was not singular but could fragment. One part might linger in the burial mound, another might join the ancestors, while yet another portion could be reborn in a descendant. What’s clear is that the Vikings showed a constant concern for a smooth transition between this life and the next.

A range of funerary practices

The Vikings developed complex funeral rites around these beliefs. Archaeological sites across Scandinavia and beyond reveal an array of burial customs, although researchers are still working to complete the picture.

The most remarkable feature of Viking funeral rites is their great diversity. Both burial and cremation were common, but researchers suspect that other, less traceable practices also took place, like scattering ashes or casting bodies into water.

A striking element of Viking burials is the mound constructed above the cremation site. These mounds came in all shapes and sizes.The so-called royal mound was gigantic, while others were barely noticeable. The mounds could stand alone or in clusters. Some were marked with standing stones or surrounded by rock circles, others were left unadorned.

Beneath the mounds, the dead were laid to rest with belongings meant to accompany them beyond the grave—clothing, tools, weapons, provisions for the journey ahead, sacrificed animals, and, occasionally, sacrificed humans.

But there is no consistent pattern in how grave goods were arranged in Viking burials, despite the intentionality. Items could be placed at the head, feet, or sides of the body, and the inclusion or positioning of objects like weapons, tools, or animal remains often varied by region, time period, and the status or gender of the deceased.

(The graves of ‘woman warriors’ are changing what we know about ancient gender roles)

Sailing beyond

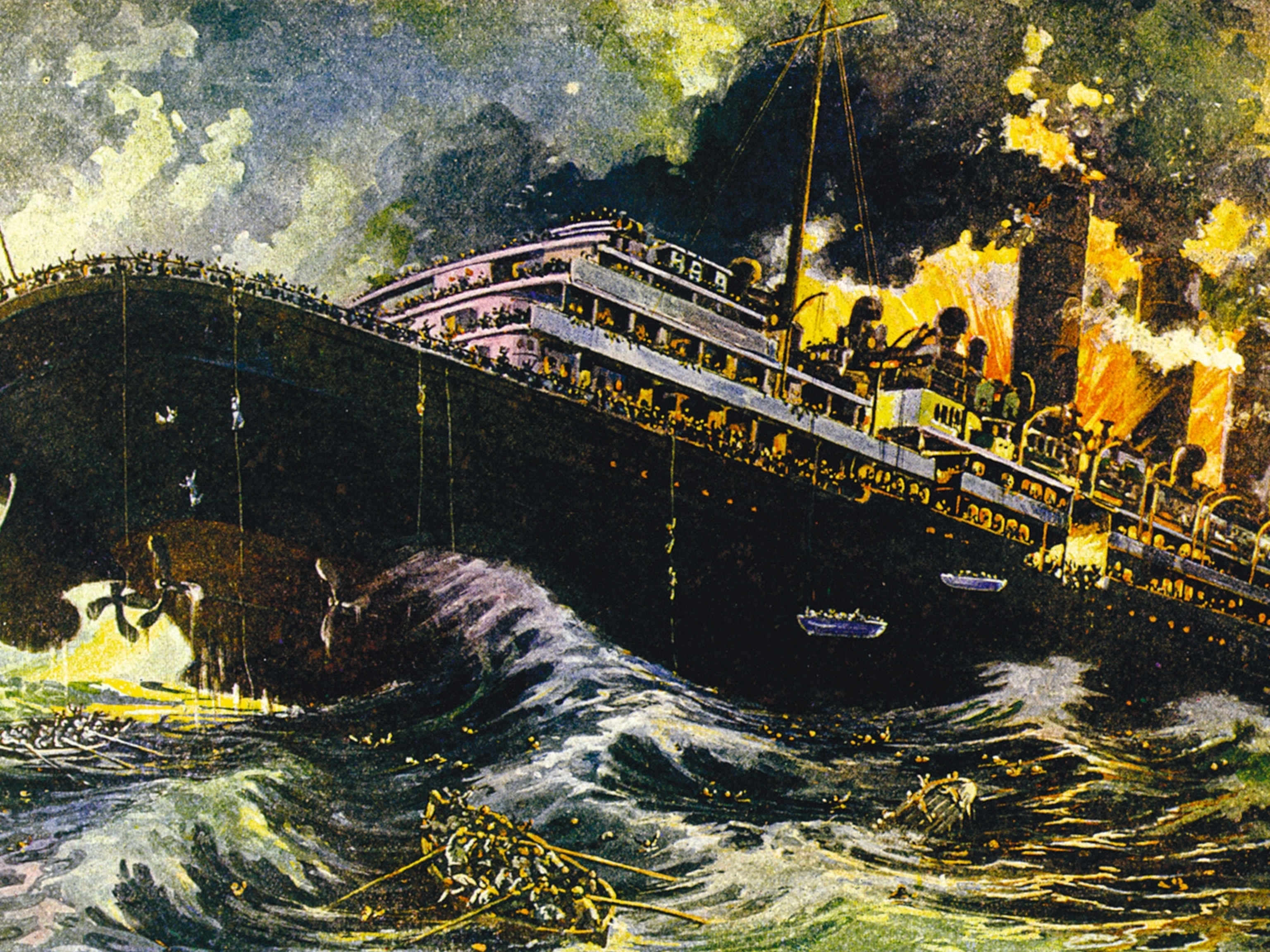

A boat burial stands out as one of the most characteristic Viking funerary practices, although it was not the most common. Archaeological evidence shows this type of burial involved elaborate rituals that probably spanned days, even years. Ceremonies would have included large quantities of alcohol, music, the sacrifice of animals, and, at times, even the rape and sacrifice of enslaved people.

In some cases, weapons were displayed and heroic deeds recited to honor the dead. Horns were blown, and skalds (poets) performed. According to Ahmad ibn Fadlan, a traveler and diplomat of the Abbasid Caliphate who witnessed a Viking funeral in the 10th century, mourners would drink heavily and sing. "For they [drink] unrestrainedly, night and day, so that sometimes one of them dies with his wine cup in his hand."

A funeral pyre

Archaeological studies reveal that Viking boat burials often included intricacies beyond mere interment. One of the most striking Viking burial ships found to date is the Oseberg in Norway. Buried in A.D. 834 under a mound, it contained the remains of two women laid to rest with sumptuous grave goods, as well as a large number of sacrificed animals: at least 15 horses and six decapitated dogs, with the head of an ox placed on a bed. More sacrificed animals were placed around the boat.

Detailed carvings on the ship’s bow and stern depict intertwined serpents and mythological figures, symbolizing protection for the deceased on the voyage to the afterlife. The placement of animal remains, such as those of horses, dogs, or oxen, was highly ritualized, reflecting beliefs in their role as spiritual guides or sacrifices ensuring safe passage. Grave goods, like finely crafted weapons with decorative inlays and imported luxury items, were positioned carefully—in some instances aligned with cardinal points, indicating cosmological symbolism. The posture of bodies, sometimes seated upright or laid with arms extended, appears to emulate readiness for travel or command, reinforcing the theme of the journey beyond death.

The funeral vessels came in all shapes and sizes. Sometimes a mound was built on top. In some cases, instead of burying a whole boat, a few boat timbers were placed in the grave or stones were arranged on the surface to suggest the shape of a boat. Within the graves, funeral items were similar to those found in the mound burials. The bodies were buried in a range of postures: seated, lying on their sides, or even occasionally positioned as if at the helm of a ship.

('100-year find’: Enormous Viking ship holds surprising clues on burial rituals)

Bespoke burials

Viking burial traditions have attracted a lot of attention from archaeologists because of their impressive mounds and burial boats. But understanding the significance of these burial traditions remains a challenge for researchers. Drawing on recent analyses of the Old Norse literary tradition, ethnohistorical data, and archaeological evidence, archaeologist Neil Price has proposed an original interpretation that seeks to explain the fact that virtually no two Viking graves are exactly alike.

Price suggests that Viking funerals were personalized performances, shaped by the story of the individual who had died. In a culture rich in oral tradition—where sagas, skaldic verse, and the Poetic Edda (a collection of poems and prose) preserved history and myth—the funeral may have been a final act of storytelling.

Grave goods often hint at these narratives. In some burials, game pieces resembling chess have been found, likely symbolizing the deceased’s strategic mind or warrior skill. In others, imported silks, Frankish glassware, or Arabic coins point to long-distance trade connections. In the Gokstad ship burial discovered in Norway, dating from the ninth century A.D., shields and even a tent were buried with the deceased, signaling both martial prowess and readiness for the afterlife. Price argues that although there is a general trend, each burial becomes a unique event intended to honor the departed.

(Facts vs. fiction: How the real Vikings compared to the brutal warriors of lore)

The Salme ships

Sometime between A.D. 650 and 750, a band of warriors from the Mälaren region in east-central Sweden set out on an expedition across the Baltic Sea. They landed on the island of Saaremaa, located along a strait crucial for maritime routes. Whether the voyage was a military or diplomatic mission remains uncertain, but what happened on the Estonian shore was undeniably violent; many Vikings lost their lives. Survivors hauled two ships over a hundred yards inland to what is now the village of Salme. There, they buried the vessels about 40 yards apart, interring the bodies of more than 40 fallen comrades.

Most were young, tall men, averaging five feet eight inches in height, and several bore signs of blade wounds. DNA analysis revealed that four of the dead were brothers. In Salme I, seven men were likely placed upright in a seated position; in Salme II, 34 others were stacked in four layers, some of which were separated by sand.

The burials were carried out with a remarkable degree of formality. This indicates that the dead were buried in accordance with Viking customs and without concern that enemies might loot the grave goods. The orderly interment and absence of looting suggest the survivors had time to conduct rites without fear of interruption.

The Salme ships provide the earliest archaeological evidence of Scandinavian sailing vessels used in warfare in the eastern Baltic. The ships were clinker-built with overlapping planks and fastened with iron rivets. Excavators recovered more than a hundred arrowheads around the hull, many of which were stuck in the ship’s timbers—offering rare physical evidence of naval combat.

Salme swords and sacrifices

The bodies of the warriors had been carefully placed inside the ships and covered with large round shields made of wood and cloth (probably cut from the sail). The swords of the dead were placed next to them; some had been ritually bent. Grave goods were placed alongside the dead, mainly Scandinavian in style. These included ornamented combs made of deer antler, small padlocks, beads, pendants made of bear canine teeth, bronze and iron plaques, and arrowheads. Bone remains of various animals that were sacrificed during the funeral have also been found, such as sheep, pigs, cows, and several dogs. One dog was decapitated, while another had been cut in half.

The Viking ships of Saaremaa

Also found in the Salme ships, scattered among the bodies, were more than 300 pieces from a game called hnefatafl. This was a board game of strategy similar to chess. The pieces are made of whalebone and walrus ivory. One piece is particularly interesting. It was found in Salme II and had been placed in or near the mouth of one of the most decorated skeletons. That piece represents the “king” in hnefatafl. Researchers presume that this was a deliberate gesture aimed at emphasizing the elevated status of this individual in relation to the rest of the group.

Ongoing studies

The Viking board game hnefatafl carries unmistakable military overtones. Played on a square board, it pits a smaller defending force, led by a king positioned at the center, against a larger group of attackers. The goal was for the king to be guided safely to the board’s edge without being captured by the enemy. The game was not merely entertainment; it mirrored battlefield tactics and may have served as a tool for teaching strategic thinking. Boards and pieces have been found in high-status burials, suggesting that mastery of the game was associated with leadership, intelligence, and martial prowess. The “king” found in the Salme II burial may have served as a cautionary tale, symbolizing the disastrous consequences of failure in war. In this case, the fallen king never reached the edge.

Among the thousands of Viking age graves known today, the Salme ships stand out for the wealth of information they provide, not only for how these warriors died but also for how they were buried. Archaeologists continue their meticulous study of the Salme ships as well as newer discoveries, like the 50 Viking graves unearthed in the Danish village of Åsum in 2024. By analyzing artifacts, skeletal remains, burial contexts, combat experiences, and cultural memories of Viking warriors, they bring to light the elaborate ways these societies honored and remembered their dead.

Preparing for a long journey