The radical wartime diet that saved Britain in World War II

A focus on certain types of power foods helped the nation survive a blockade.

Eighty years since the end of World War II, the British are recalling many battles fought on the path to victory. Yet one seldom, if ever, gets mentioned, and it was one of the most consequential—the battle to feed an island people under siege.

In the decade before the war, Britain imported around 22 million tons of food a year, almost two-thirds of its food supply. But early in 1940 Adolf Hitler set out to starve the British by sending swarms of submarines into the North Atlantic to sink the convoys of ships bringing essential foods from Canada and America. As a result, during the war, Britain’s food imports were halved to around 11.5 million tons.

Globally, more people died during the war of starvation than from military action, but the British never starved. In fact, they ate the healthiest diet they had ever enjoyed. The effect on children was particularly striking: at the end of the war, the majority of them were healthier than they were at the beginning. Infant mortality rates were the lowest on record. Bone growth was greater and, on average, they were taller than before. The rate of every diet-related disease declined dramatically.

How did this happen?

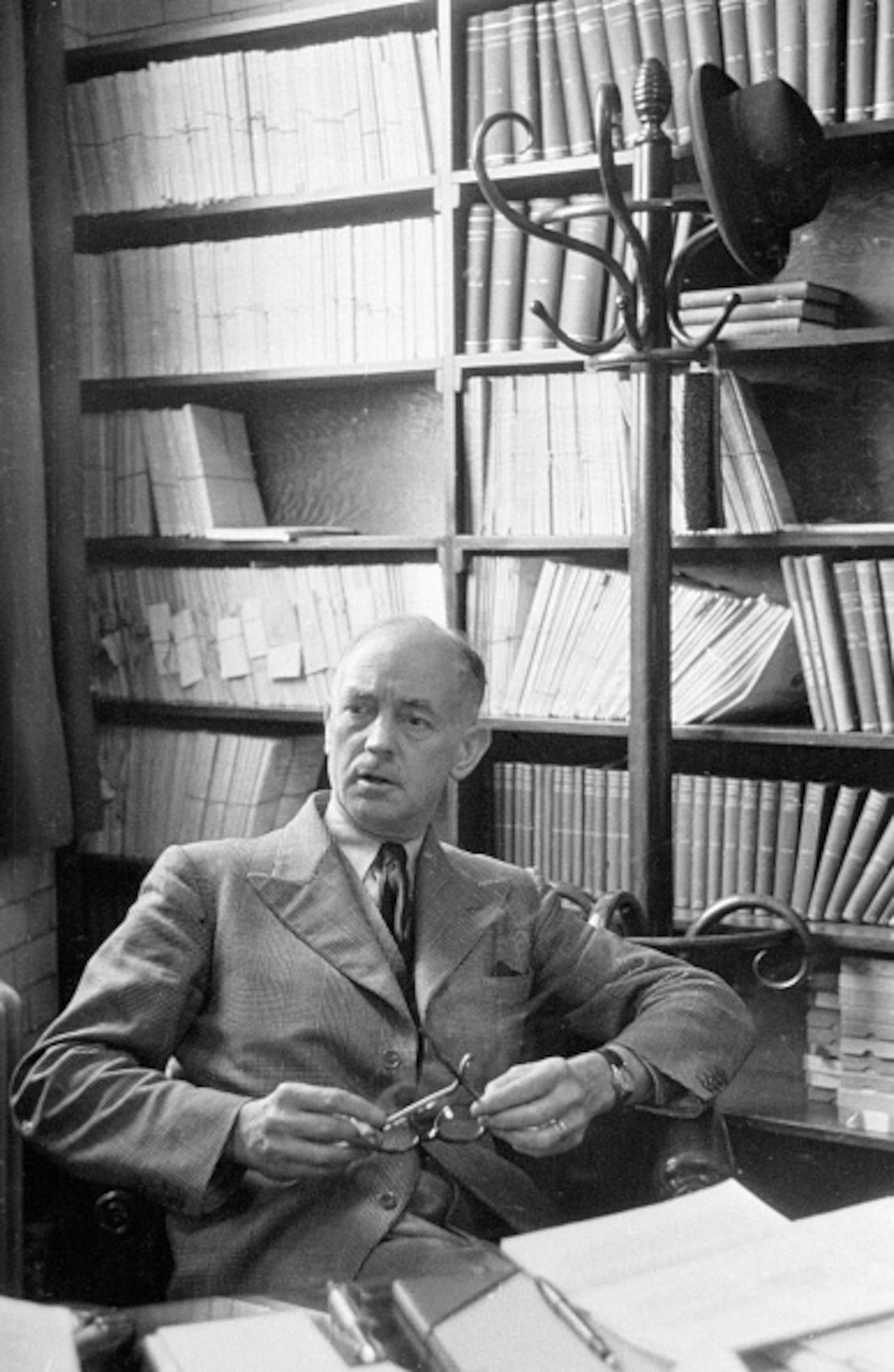

Few people ever find themselves in the position to execute an idea as radical as transforming the diet of an entire nation. But that is what happened to Jack Drummond, a scientist called in by the Ministry of Food, a body set up in London soon after the outbreak of war in 1939. It’s almost as though the moment had been awaiting the man: In the 1930s, Drummond had carried out the first thorough historical investigation of the national diet and, on the eve of the war, published it as a book blandly titled The Englishman’s Food. It was a unique combination of closely observed social habits and biochemistry, and a scientific skewering of the ravages inflicted on public health by widespread ignorance of how nutrition worked.

Drummond had an authority that was hard to challenge. He was the protégé of Casimir Funk, a biochemist who coined the word ‘vitamine.’ Drummond, dropping the final “e,” identified and named vitamins A, B and C. At the age of 31 he became the first professor of biochemistry at University College London, where he recruited a young research assistant, Anne Wilbraham, who worked with him on the book, sharing the authorship credit.

(The last voices of World War II)

The book’s field research covered what began as an affair (Wilbraham was 13 years younger than Drummond) and, after Drummond divorced, in 1940, became a marriage of two crusading minds determined to demonstrate how a balanced diet could be, at the most basic level, a lasting force for social equity—and, as it turned out, a war-winning policy.

No one had ever written a multi-century history of a people based on what had passed through their stomachs. Drummond’s most incisive observations were drawn from the Industrial Revolution, a deeply disruptive social experience. Drummond found that by the 1830s, Britain’s new urban working class were seriously ill-fed but the consequences of this were not understood: “There was a fear,” he wrote, “that many of the governing classes then felt lest the half-starved workpeople should ever bring about an organized movement to demand higher wages and better conditions.” For the next century, as wages improved, so did the diet of the working class, but Drummond had uncovered a paradox: The diet of the poor was needlessly inadequate in essential foods while the diet of the wealthy suffered from an abundance of harmful gluttony, including too many fatty meats and game birds and puddings galore, both savory and sweet.

The war gave him the power to correct that. Strict rationing, applied to everyone, meant that gluttony was curtailed and the poor no longer wanted for basic essentials.

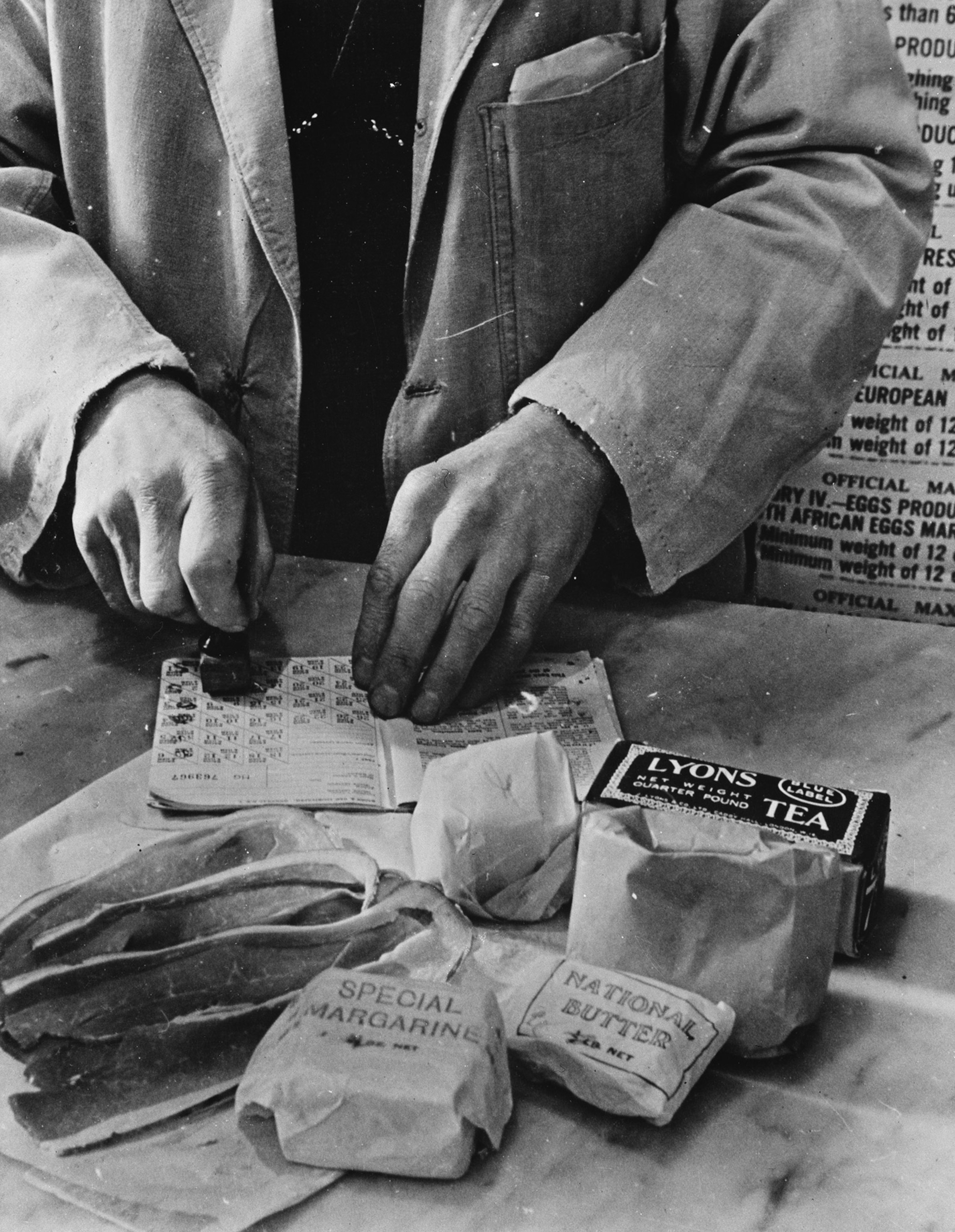

Drummond gave priority to the foods that provided essential vitamins, like bread, milk and vegetables. Every family had a ration book with coupons, the size of a postage stamp. The worth of the coupons was decided by the quantity and type of food they could be exchanged for, which constantly changed depending on the food supply.

(10 remarkable World War II museums around the world)

Drummond made the most of the space available in the ships bringing food across the Atlantic, a critical lifeline amid the losses inflicted on the convoys by German submarine wolf-packs. At the worst point of the war, half a million tons of shipping went to the bottom of the Atlantic a month. He knew that in California and Wisconsin, dried eggs and milk were being produced, which would make far more efficient use of the precious space, and took advantage of that. Imports of fruit, nuts and eggs in shells were greatly reduced to save space.

Another target was sugar. Britain had long been on a sugar binge, supplied by plantations in the colonies. In the preceding century the consumption of sugar had risen five-fold, with consequences only dentists could celebrate. In the war, the amount of sugar imported was cut to half of the pre-war level. (In 1953, to help celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, prime minister Winston Churchill—against the advice of ministers—ended the rationing of sugar and candy. A “sugar craze” followed and the nation’s long-term health suffered from the return of diet-related diseases like obesity and type two diabetes.)

The rationed diet was supplemented by what people could provide for themselves. People dug up flower beds and planted vegetables. Empty lots in cities were turned over to families to cultivate whatever they could grow. In the country, rabbit became a popular meat. A meatless pie, the Woolton Pie, laced instead of meat juices with a dark extract of brewer’s yeast—and named for Drummond’s boss, Lord Woolton, Minister of Food—became a national staple. (It mixed a pound each of diced potatoes, cauliflower, turnips, and carrots with a tablespoon of oatmeal for the filling and topped it off with a potato or wheatmeal crust, to bake in the oven until nicely browned.)

A typical weekly food ration under Drummond’s diet in 1942 allowed for four ounces of bacon and ham per person; two ounces each of butter and cheese; four ounces each of margarine and cooking fat; eight ounces of sugar; extra meat to the value of one shilling and two pence; and two ounces of tea. Monthly, Britons could receive three pints of fresh milk and a packet of dried skimmed milk; one egg in the shell and one packet of dried egg; and a pound of preserved fruit (jam) every other month. These basic were supplemented by vegetables as available, many of them home-grown.

(See maps of nine key moments that defined World War II)

And so it was that nobody went hungry. Food shortages persisted after the war but rationing gradually tapered off and ended in 1954.

War accelerates scientific innovation, usually for waging war: Britain pioneered radar, the jet engine and, with America, nuclear weapons. Drummond did something different with that opportunity—he significantly advanced the health of the British people. After the war, the American Public Health Association, citing Drummond for an award, said his work was “one of the greatest demonstrations in public health administration that the world has ever seen.” Of course, with the end of rationing, a top down directed national diet was no longer possible, as the sugar binge of the 1950s demonstrated. Nonetheless, important lessons had been learned and were still used as official guidance in one vital area, the menus of school meals. Beyond the school gates, alas, there was no such discipline.

Drummond was knighted for his work, but his life ended in a tragic way that still leaves a greatly disputed cold case.

In August, 1952, he set off with Anne and their young daughter for a driving holiday in France. One evening, in Provence, they pulled off the road to spend the night sleeping in their car. In the morning, Drummond and Anne were found shot in the car; their daughter was found nearby, beaten to death with a rifle butt. Gaston Dominici, a 75-year-old farmer, was arrested and found guilty of the murders. But after three years on death row the sentence was reduced to life imprisonment and, in 1960, he was released because of his age and ill health. His family have always insisted on his innocence.

There was no apparent motive. A persistent conspiracy theory has it that Drummond, concerned about the contamination of milk by new insecticides applied to grazing land, was using the trip as cover for investigating a plant making insecticides in Provence. Still, there is no evidence at all that Drummond had any taste or talent for industrial espionage.

However, he had been looking at the broader impact of agrochemicals on the food chain, and at the emergence of processed foods. He was planning a new edition of The Englishman’s Food but his research had barely started. It’s quite likely that, had that book been written, it would have been, in its own field, as much of a wake-up call as Rachel Carson’s revelations about pesticides were on the environmental movement a decade later in her book Silent Spring.