General Grant's surprising rise from cadet to commander

Early in the Civil War, Union forces were struggling in the East but winning in the West, where a relentless Ulysses S. Grant scored victory after victory to ascend through the ranks.

When the U.S. Civil War began the morning of April 12, 1861, no one would have identified Ulysses S. Grant as the man who would lead the Union Army to victory. A former army officer, Grant had left the military in 1854. He and his family lived in Missouri before relocating to Galena, Illinois, in 1860. When war broke out, Grant was working as a clerk in his father’s leather store.

Galena was a small farming town in 1861, and it took six days after the attack on Fort Sumter, for news of the war to reach it. The citizens were galvanized to fight against secession, and a town meeting was held to rally to the cause. Grant led the proceedings where, after several rousing speeches by representatives of different political parties, the unified people volunteered to form a company of soldiers.

Before the war

Born April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, Hiram Ulysses Grant was the eldest of Jesse and Hannah Grant’s five children. In 1823 the Grant family moved to Georgetown, Ohio, where young Ulysses would grow up. His father was a tanner, a profession in which Ulysses had no interest. In his memoirs Grant wrote, “I detested the trade . . . but I was fond of agriculture, and of all employment in which horses were used.” He began schooling at age five and continued through his teens when he was surprised to learn that his father had secured him an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

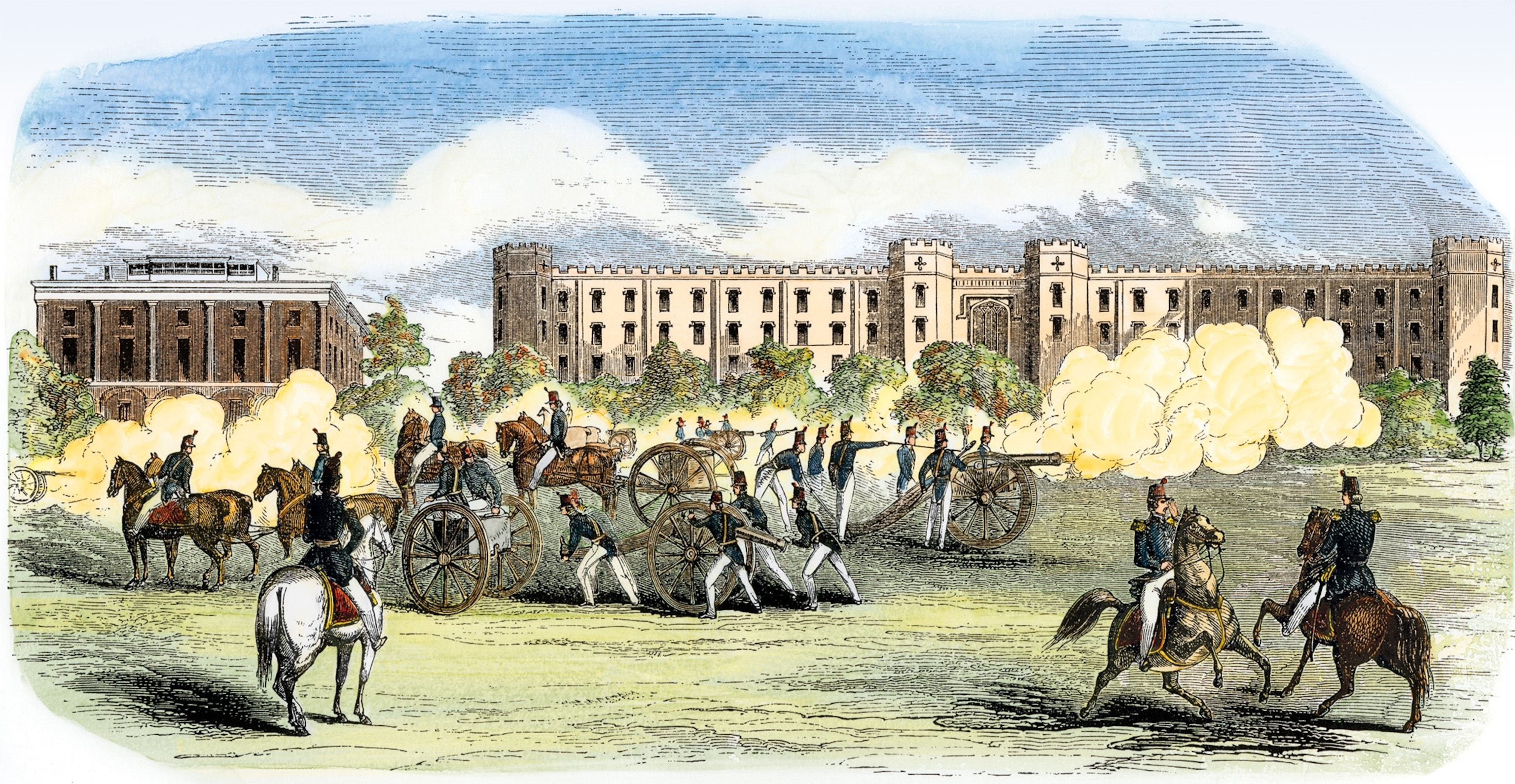

Grant began his studies at West Point in 1839. He was a somewhat mediocre student with an excellent reputation for his equestrian skills. He studied next to many men whom he would later fight alongside and against. Before graduating in 1843, he would encounter more than 50 future Civil War generals, an experience that would serve him well in the war to come.

Appointed a brevet second lieutenant, Grant’s first assignment was the Fourth Infantry regiment stationed at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. There he fell in love with Julia Dent, the sister of his West Point roommate, and was engaged to her before being called up to fight in the Mexican War, serving in many major battles and twice being brevetted for bravery. After the war, Grant returned to Missouri and married Julia in 1848. He resigned from the U.S. Army as a captain in 1854, first settling in Missouri, and then relocating in 1860 to Galena, Illinois.

West Point woes

Battles on the river

After fighting broke out at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Grant knew which side he was on. In a letter to his father, Jesse, in April 1861, he wrote, “There are but two parties now, Traitors & Patriots and I want hereafter to be ranked with the latter.” After organizing the Illinois volunteers and receiving a quick promotion, Colonel Grant’s 21st Regiment was transferred to Missouri in July 1861 where more regiments fell under Grant’s command, earning him another promotion, this time to brigadier general.

Grant’s skills attracted the attention of the Union commander of the Department of the West, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, who tapped Grant to plan a campaign down the Mississippi River, perhaps the most vital transportation artery in the United States at the time and key to weakening the Confederacy. Setbacks occurred when President Lincoln removed Frémont from command after he had announced an intention to free enslaved people belonging to traitors. Lincoln was not ready to antagonize enslavers in contested Border States like Missouri and Kentucky, but Frémont’s parting gift to the Union was his selection of Brig. Gen. Ulysses Grant to command troops at Cairo, Illinois.

On November 7, Grant steamed down the Mississippi with 3,000 men and seized a Confederate outpost at Belmont, Missouri, across from heavily fortified Columbus, Kentucky, where Rebel batteries brooded over the river. His troops, raw recruits from Illinois and Iowa, celebrated wildly, which enabled Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk to ferry reinforcements across the river and block Grant’s escape route.

Euphoria gave way to panic when Polk bombarded Grant’s forces. Some Union officers wanted to surrender, but Grant would have none of it. “We cut our way in and can cut our way out,” he said. By extricating his forces from Belmont, Grant earned a reputation as one who would never give up.

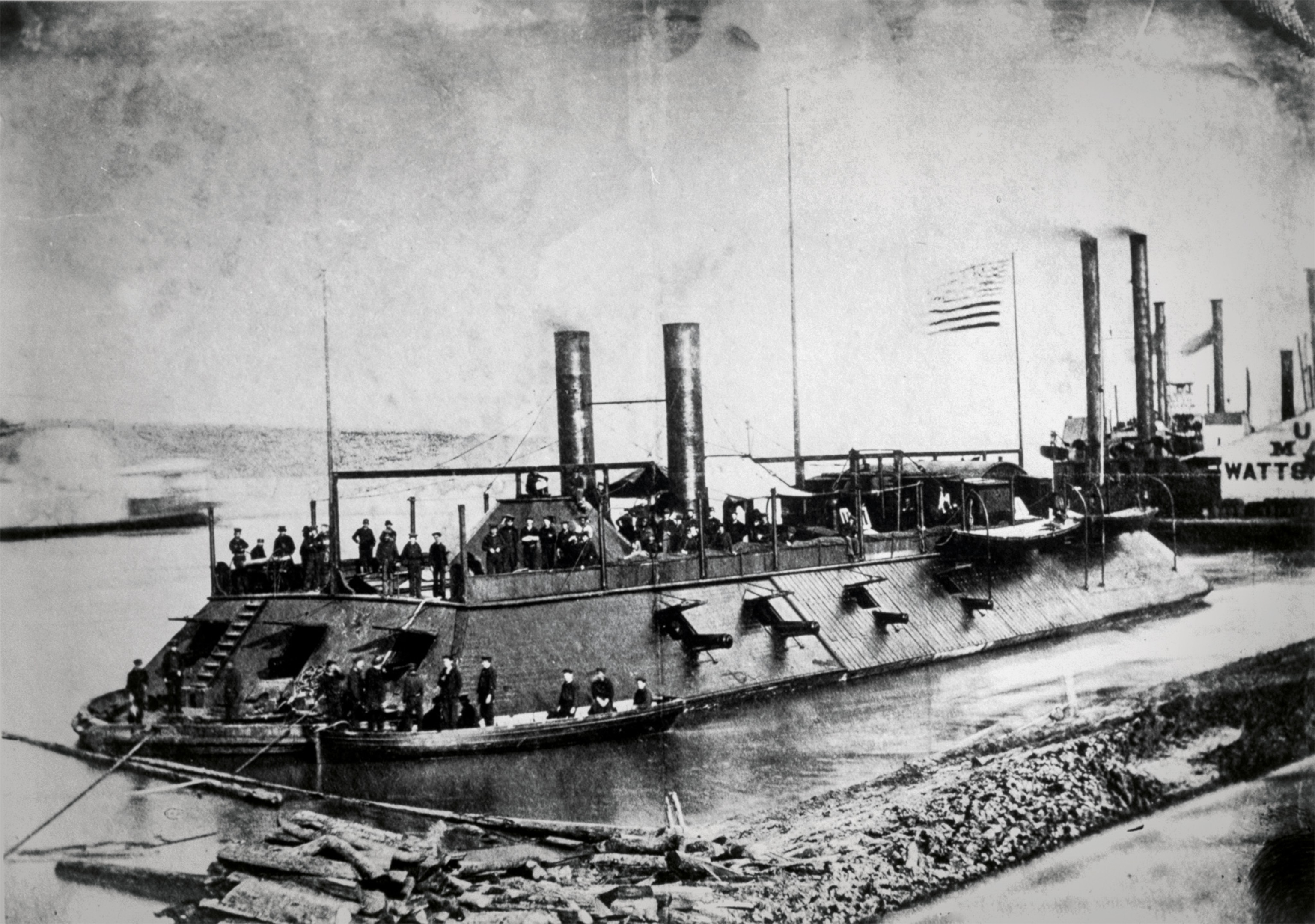

In late January 1862 Grant left the Mississippi and advanced southward to the Tennessee River with 17,000 men in steamboats, shielded by ironclad gunboats commanded by Flag Officer Andrew Foote. The first ironclads to enter battle during the war, they opened fire on February 6 at Fort Henry, a low-lying, flood-swept Confederate bastion whose gunners were pounded into submission before troops Grant sent ashore reached the fort.

That victory helped clear the way for him to follow the Tennessee River deep into enemy territory. But before that could happen, he first had to deal with Fort Donelson, situated nearby on the Cumberland River and crucial to the defense of Tennessee’s capital, Nashville.

Set on high ground and heavily defended, Fort Donelson withstood attack by Foote’s ironclads but was hemmed in by Grant’s troops under Brig. Gens. John McClernand, Charles F. Smith, and Lew Wallace. The three Confederate generals who shared command of the fort—John Floyd, Gideon Pillow, and Simon Buckner—tried to break out on February 15, but Grant repelled their forces.

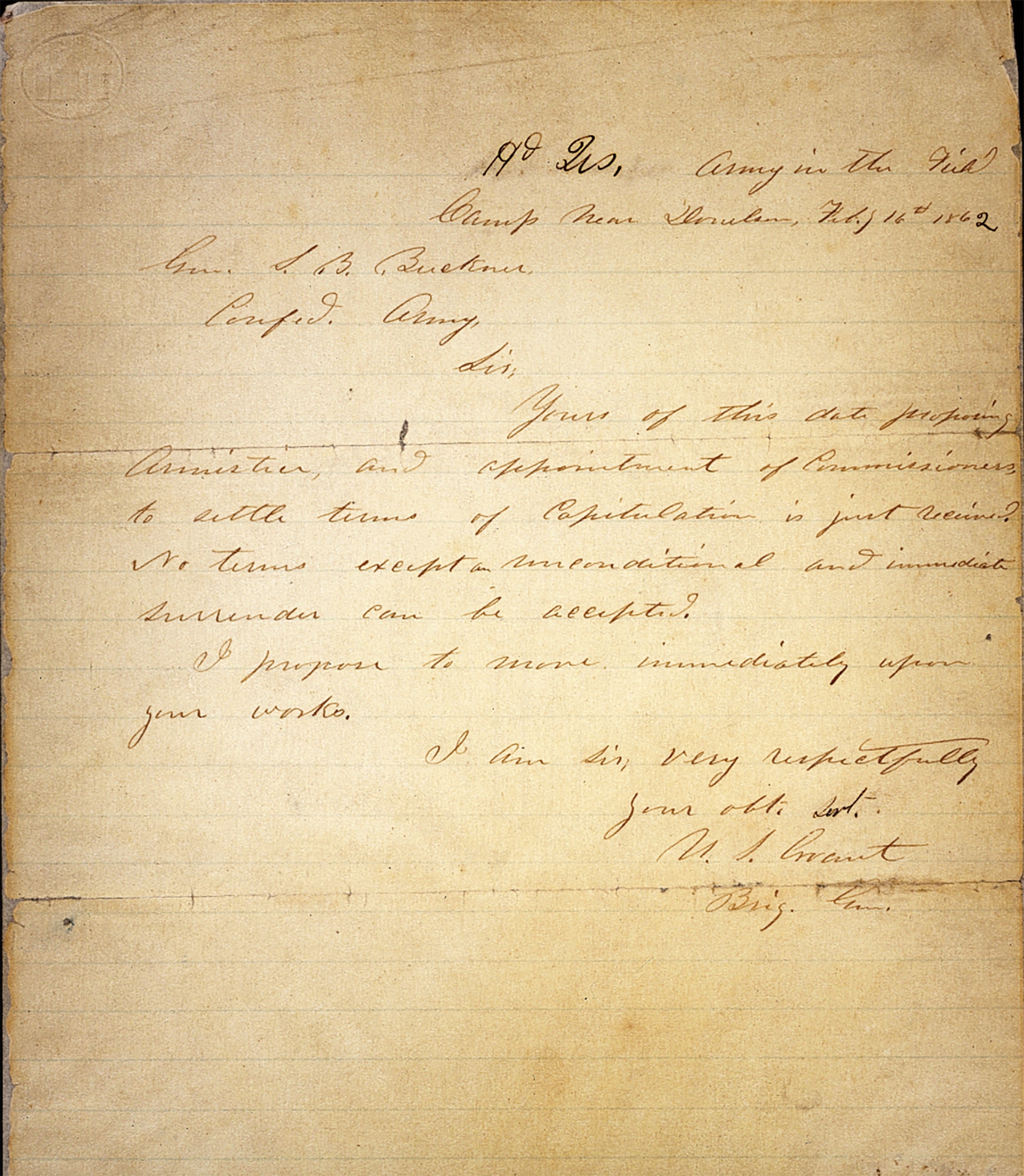

That night, Floyd and Pillow fled by boat, leaving 13,000 men behind under Buckner, who sought a truce. Buckner was a friend of Grant’s at West Point and perhaps expected a gentler answer than the one he received. “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted,” Grant replied, and Buckner yielded.

Grant’s past experiences at West Point and in the Mexican War gave the Union an edge. He knew many of the men he was fighting against and used that knowledge to his advantage. In his memoirs Grant wrote: “I had known General Pillow in Mexico, and judged that with any force, no matter how small, I could march up to within gunshot of any intrenchments he was given to hold. . . . I knew that Floyd was in command, but he was no soldier.” Simon Buckner was a year behind Grant at West Point, and the two had been friends there. When Buckner came to discuss the terms of surrender, Grant later recalled, Buckner told “[me] that if he had been in command I would not have got up to Donelson as easily as I did. I told him that if he had been in command I should not have tried in the way that I did.”

News of Grant’s victory—which led to the capture of Nashville—made him a national hero. His initials, U. S., came to signify“unconditional surrender”—and the determination of Uncle Sam to crush the rebellion. Grant’s success at these two battles would establish his bona fides as a leader to be reckoned with.

Guns along the Mississippi

Bloodbath at Shiloh

After capturing Fort Donelson and advancing to the rank of major general, Grant resumed his advance up the Tennessee in March and disembarked at Pittsburg Landing, on the river’s west bank just above the Tennessee-Mississippi border. His objective was Corinth, Mississippi, a vital rail junction some 20 miles away. It was held by Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, the opposing commander in the West and one of the highest-ranking Confederate officers.

Grant assumed that Johnston would remain on the defensive and planned to assault Corinth once Union reinforcements arrived under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, who had taken Nashville. Grant’s trusted subordinate, Brig. Gen. William Sherman, set up camp near a little church called Shiloh. Like Grant, Sherman did not fear assault, and he did not order his men to entrench. Meanwhile, 40,000 Confederates led by Johnston advanced undetected from Corinth to within a few miles of Sherman’s position at Shiloh.

At dawn on Sunday, April 6, Johnston sent Maj. Gen. William Hardee’s corps slamming into Grant’s startled forces. “My God, we are attacked!” cried General Sherman; many of his men were still in their tents. They fell back along with the exposed forces of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss as two more Confederate corps under Maj. Gens. Braxton Bragg and Leonidas Polk entered battle. The swarming Confederates soon lost cohesion, however, allowing their foes to regroup. By midday the Federals had established a new battle line near a sunken road and field called the Hornet’s Nest for the furious fighting there.

Around two that afternoon, Johnston rode forward to rally his troops and was hit by a bullet that severed an artery and later that day took his life. His successor, Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, continued to throw Confederate forces into the deadly Hornet’s Nest. Union forces held out long enough for Grant to prepare a last line of defense near the river. Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace ended up on the wrong road and arrived belatedly, but Sherman stood fast on Grant’s right flank while Union gunboats on the river blasted the oncoming Confederates.

With daylight waning, Beauregard concluded that his victory was “sufficiently complete” and postponed further attacks, expecting that Grant would retreat across the Tennessee that evening. Grant, however, believed that the Union could turn things around; he later recalled, “So confident I was before firing had ceased on the 6th that the next day would bring victory to our arms if we could only take the initiative, that I visited each division commander in person before any reinforcements had reached the field.”

Fortunately, Union forces were reinforced by Buell, newly arrived from Nashville, who ferried thousands of men across the river overnight. Early on April 7, Grant counterattacked with his fresh troops and pushed the Confederates back. “This day,” wrote Grant, “everything was favorable to the Union side. We had now become the attacking party. The enemy was driven back all day.”In midafternoon Beauregard cut his losses and withdrew to Corinth, shielded by his rear guard under Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose cavalry repulsed pursuing Federals the following day at Fallen Timbers.

Grant had held his ground at Shiloh, a technical victory overshadowed by the appalling human cost: more than 13,000 Union casualties and nearly 11,000 Confederate losses. It was by far the bloodiest battle yet fought on since the nation was founded. Beauregard’s fine reputation in the South was spoiled, and Grant faced a storm of criticism for letting down his guard. Some called for his dismissal, but Lincoln offered him a memorable endorsement: “I can’t spare this man; he fights.”

Brothers in arms

Vicksburg campaign

In the months following Shiloh, Union commanders debated their next moves. They succeeded in taking Corinth, Mississippi, by May 30, 1862. Because of the controversy surrounding Shiloh, Grant was briefly sidelined; he was reinstated in July as the commander of the Army of the Tennessee by the senior Union Army commander in the western theater, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck.

Union forces began to then turn their attention to new Confederate targets along the Mississippi River. Many agreed that the obvious choice was Vicksburg. Known as the Gibraltar of the Confederacy, Vicksburg was perched on bluffs high above the Mississippi, shielded by big guns that deterred assault by river and swampy surroundings that discouraged attack by land. Yet Grant was determined to take that Rebel stronghold on the river’s east bank, come hell or high water, and gratify President Lincoln who had stood by him after Shiloh.

One of the few things Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis agreed upon was the strategic significance of Vicksburg. It was the vital artery through which the Confederacy received shipments from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, including European weapons imported through Mexico to avoid the Federal blockade. Vicksburg was the “nailhead that held the South’s two halves together,” Davis said.

The city’s batteries also divided the Union by preventing its forces from moving freely between Federal-occupied New Orleans and Memphis and its western farmers from shipping produce downriver to distant markets. “Vicksburg is the key,” Lincoln said. “The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

In late January 1863 Grant moved his headquarters from Memphis to Young’s Point, Louisiana, upriver from Vicksburg, and conducted “experiments” aimed at circumventing its defenses. Attempts failed to find a way through bayous north of town that would allow Grant to approach Vicksburg from the east, where the ground was firmer and the city more vulnerable. So he planned instead to march south, well west of the city’s batteries, while gunboats led by Adm. David Dixon Porter ran that gantlet. Aided by Porter’s fleet, Union forces would then cross the Mississippi and move inland, sweeping around to the east of Vicksburg like a snake encircling its prey.

By leaving the river, which served as his supply line and avenue of retreat, Grant risked being cut off. Sherman urged him to abandon the plan, arguing that when “any great body of troops moved against an enemy they should do so from a base of supplies” and never lose touch with that base. Grant thanked him for his “friendly advice” but pressed ahead. He left Sherman’s corps north of town temporarily to preoccupy Vicksburg’s defenders by staging diversions at Haynes Bluff and Snyder’s Bluff. If all went as planned, Sherman’s corps would later form the tail of the snake as Grant attacked the city.

Battlefield monuments

On the night of April 16, Porter’s ironclads steamed downriver past Vicksburg and engaged in a thunderous duel with Rebel gunners on the bluffs. “Our batteries were in full play,” observed a Confederate officer, “blazing away at the line of gunboats.” Porter’s fleet emerged largely unscathed, only to face an even stiffer test at Grand Gulf, where Grant planned to cross to the east bank. Confederate artillery there fought fiercely with the gunboats for five hours on April 29, inducing Grant to bypass Grand Gulf and march farther south to Bruinsburg, where his troops crossed safely on the 30th.

Sherman, meanwhile, was doing his part by assailing Confederates under Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson north of Vicksburg. Stevenson wrote Lt. Gen. John Pemberton, the commander at Vicksburg, that this was the “real attack” and that Federal moves below Vicksburg must be a feint. “Send me reinforcements,” he pleaded. Pemberton then recalled forces he had sent south, which served Grant’s purpose. After defeating Brig. Gen. John Bowen’s outnumbered Confederates at Port Gibson on May 1, Grant took Raymond on May 12 and entered Mississippi’s capital, Jackson, two days later.

His swift advance prevented Gen. Joseph Johnston—back in action after being wounded at Seven Pines a year earlier—from reaching Vicksburg by way of Jackson and reinforcing Pemberton. Grant made things worse for Vicksburg’s defenders by cutting the railroad from Jackson that supplied them while his own troops lived off the land by seizing crops and cattle from the populace.

Vicksburg besieged

Belatedly, Pemberton came out from Vicksburg to challenge Grant at Champion Hill on May 16. Maj. Gen. James McPherson’s corps helped Grant repulse Pemberton, who retreated to Vicksburg across the Big Black River and burned the bridge behind him. Federal engineers soon spanned the river with pontoons, and Grant launched two determined but unsuccessful attacks on Vicksburg’s defenses, on May 19 and 22, before laying siege to the city. “This is a death struggle,” wrote Sherman, who had rejoined Grant, “and will be terrible.”

Federal gunners bombarded Vicksburg, driving civilians into hastily dug caves. Cut off by land and by water, where Porter’s fleet held sway, hungry troops and inhabitants fed on horses, dogs, and rats. As the Federal noose tightened and sickness and famine spread, a Confederate soldier sent Pemberton a pointed message: “If you can’t feed us, you had better surrender us, horrible as the idea is, than suffer this noble army to disgrace themselves by desertion.”

When Pemberton sought terms on July 3, Grant first insisted on unconditional surrender but then agreed to release Vicksburg’s defenders on parole (which required them to pledge not to take up arms again). Before dawn on July 4, Pemberton surrendered the city and its forces. Grant’s triumph at Vicksburg (and Lee’s simultaneous defeat at Gettysburg) made this America’s most fateful Independence Day since 1776.

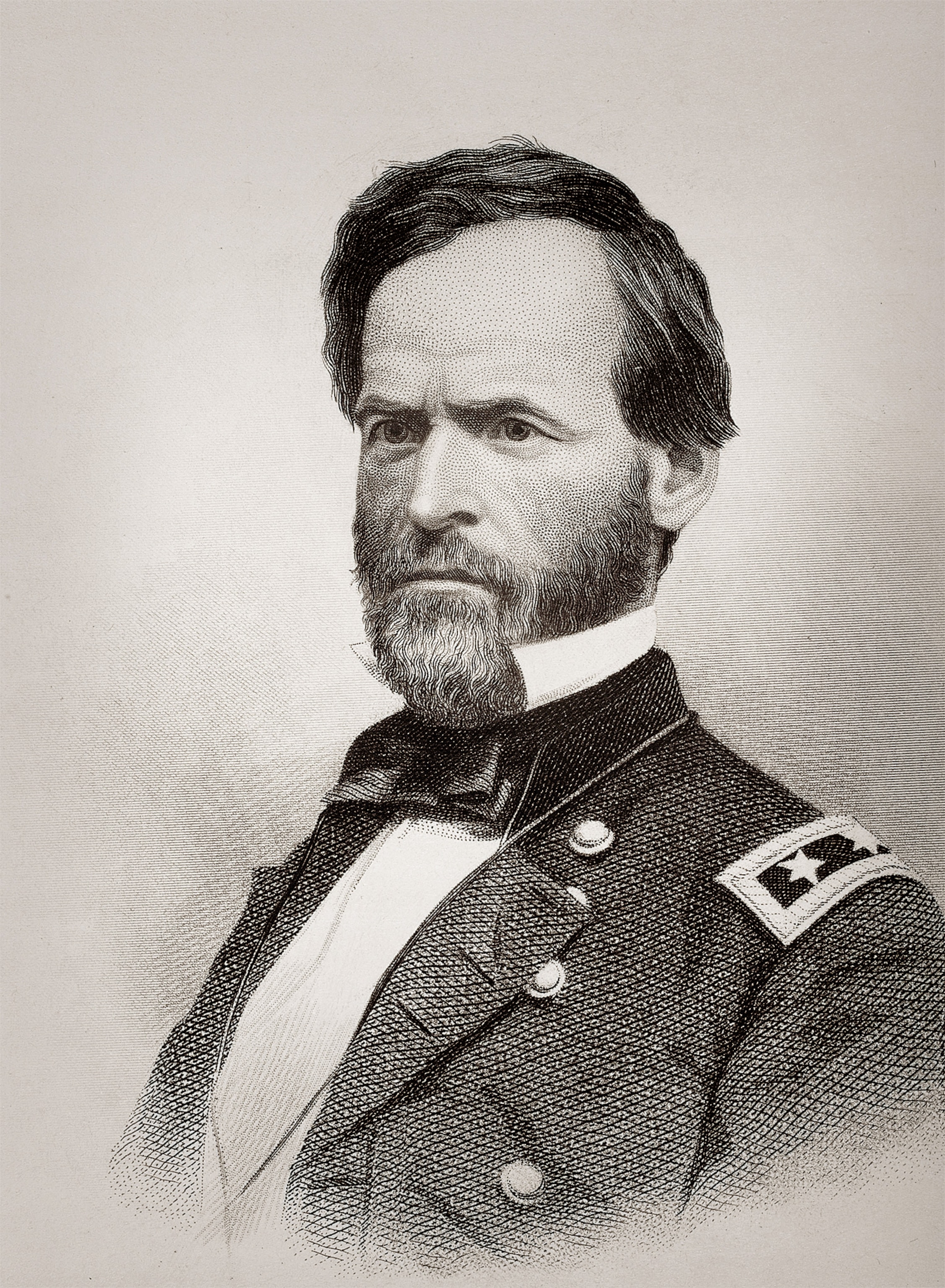

After Vicksburg, Grant and his team secured another important victory for the Union after taking Chattanooga in autumn 1863—adding another success to his track record, which Union leadership could not ignore. The war in the West brought out the best in Grant, nurturing his talents and allowing them to grow, while the war in the East had been nothing but challenging for the Union. Defeats and failed campaigns plagued President Lincoln, who found himself firing one general after another.

Lincoln saw the nation’s solution in Grant, and the nation agreed. In early 1864 Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant became the second American after George Washington to rise through the ranks and earn this honor without brevet. Grant then took command of all the armies of the United States and began planning the campaigns that would defeat the Confederacy.

When Grant received Lincoln’s commission, he humbly replied, “With the aid of the noble armies that have fought in so many fields for our common country, it will be my earnest endeavor not to disappoint your expectations. I feel the full weight of the responsibilities now devolving on me; and I know that if they are met, it will be due to those armies, and above all, to the favor of that Providence which leads both nations and men.” Grant’s road to victory would not be easy, but his tenacity, tactics, and faith in his men—from his generals to his foot soldiers—would help defeat the Confederacy and unite the nation.