This biblical villain’s tomb was lost for centuries

King Herod’s mausoleum, which long eluded archaeologists, sheds light on the ruler’s turbulent reign—and its effect on Jesus’s early life.

Dominating the arid landscape on the edges of the Judaean Desert stands a hill that was once the pinnacle of territory controlled by Herod the Great. Identified in the mid 1800s as the site of the palace-fortress built by the king, Herodium housed a luxurious oasis in the lands southeast of Bethlehem.

Even before its identification, historians had a clear vision of what this landmark once looked like, thanks to the Judeo-Roman historian Flavius Josephus. In his History of the Jewish War, written in the late first century A.D., Josephus described it as “a hill, raised by the hand of man, to be the shape of a woman’s breast.”

Comprising palaces, forts, gardens, and a theater, the complex has provided rich insights into a king whose rule shaped the early life of Jesus. Excavations in the last two decades have also cast fresh light on Herod’s turbulent reign, culminating in the stunning discovery of his mausoleum on the slopes of the hill in 2007.

(Biblical stories of Jesus' birth reveal intriguing clues about his times.)

Herod and the hill

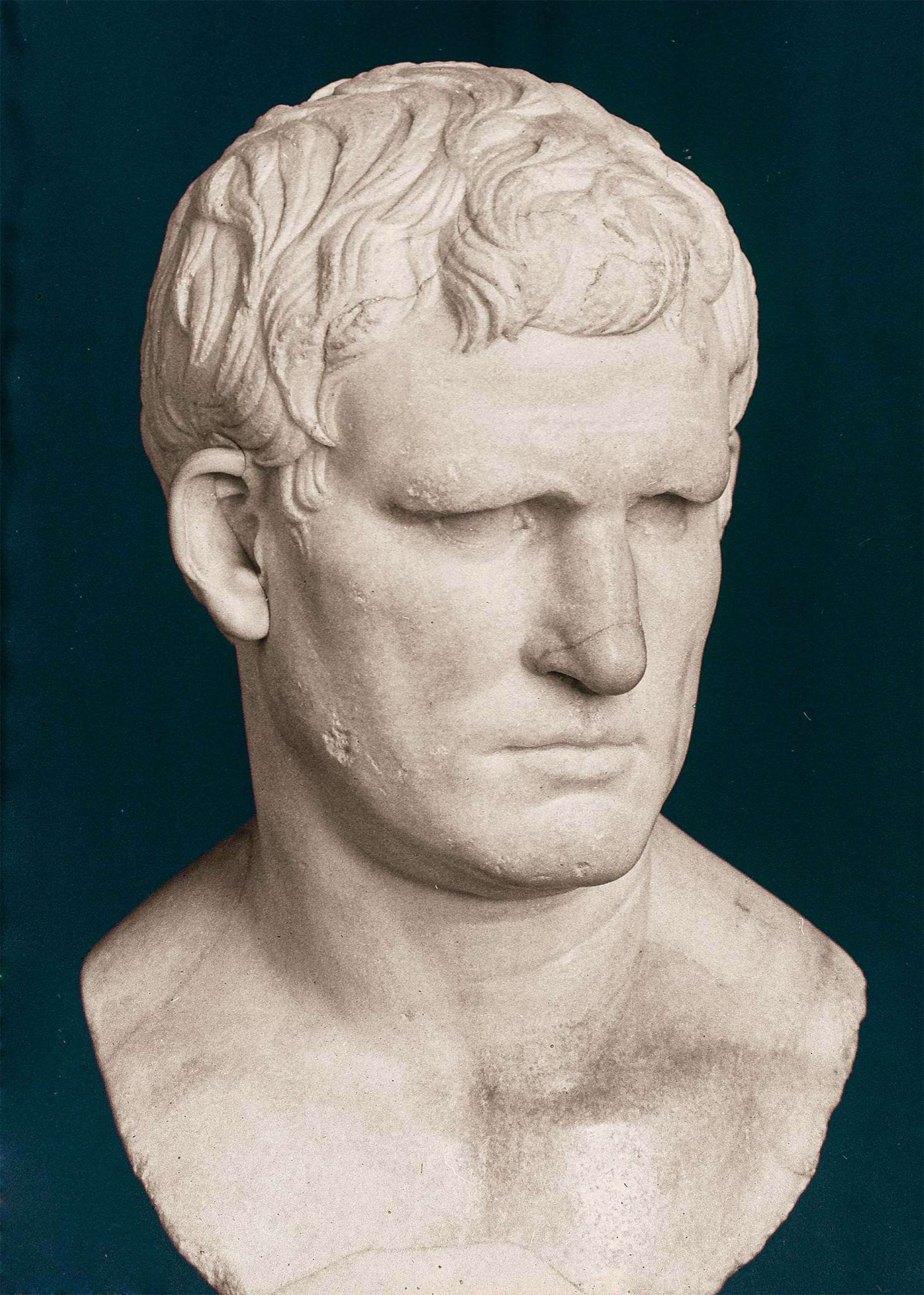

Herod the Great is remembered by Christians for his cruelty in ordering the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem following the birth of Jesus. Described in the Gospel of Matthew, the incident was enacted in medieval pageants, and its perpetrator depicted in works of art and lyrics of song as the incarnation of evil.

Herod was a beneficiary of rapidly growing Roman influence in the region. When he was born in Ashqelon in 73 B.C., Judaea was under the control of the Hasmoneans, a Jewish dynasty whose founders had rebelled against the Greek-speaking Seleucid empire the century before. In 63 B.C., when Herod was about 10, the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem, severely limiting Hasmonean control.

Herod’s father, Antipater, was a wealthy Jewish noble who admired Roman culture and was friendly with Julius Caesar. Rewarding his loyalty, Rome appointed Antipater ruler of Judaea; he in turn appointed his son, the young Herod, as governor of Galilee. Following Antipater’s death, the Roman senate appointed Herod as king of Judaea. But the new king was faced with a problem: Antigonus, a Hasmonean noble, had himself been appointed king of Judaea, backed by anti-Roman Jews, and Rome’s regional enemies, the Parthians.

In 40 B.C., near a hill near Bethlehem, the rival kings clashed. Herod defeated Antigonus, later seizing Jerusalem. To commemorate that victory, in 23 B.C. Herod decided to build a palace-fortress on the site where he fought. Enslaved people were brought in to do the heavy labor, and the skilled work of stucco and frescoes was carried out by Greek or Roman craftsmen. Herodium started to take shape.

Over the course of his life, Herod became known for massive building projects. He would oversee the lavish expansion of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, the construction of the town and harbor of Caesarea, as well as expanding the Hasmonean desert fortification of Masada.

Even by these standards, however, Herodium was an ambitious undertaking. The structure, built on the summit of the hill, measured about 200 feet in diameter. It was protected by two concentric walls and four large towers aligned with the four cardinal points of the compass. The palace-fortress was entered from below by a staircase, described by Josephus as “two hundred steps of the whitest marble” that penetrated the hilltop complex via a tunnel more than 15 feet high.

Around 10 B.C. Herod ordered the addition of dirt and sand to bulk out the summit of the existing hill to give it its distinctive mounded top that can still be appreciated today. The scope of the complex was remarkable. As Josephus observes in his account of the site, the lower settlement was sufficient “to receive the furniture that was put into them ... and containing all necessaries, that it might seem to be a city.”

Security and luxury: Desert place

At the base of the hill was Lower Herodium, consisting of a palace, Roman-style baths, and a large swimming pool surrounded by gardens. Ancillary buildings were also built that provided service and administration to the palaces.

Maintaining gardens and pools in such an arid environment was, Josephus noted, as much a feat as the architecture itself: “The water is brought from a great way off, and at vast expense, for the place itself is destitute of water.”

(These biblical queens played crucial roles in the rise and fall of ancient Israel.)

Despite his well-deserved reputation for violence, Herod valued beautiful things. The palaces were designed for the entertainment of often high-profile guests, such as the occasion in 15 B.C. when Herod entertained Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the close ally and son-in-law of Emperor Augustus. Josephus wrote how, as both palace and fortress, Herodium satisfied “security and beauty.”

The setting of Herodium was chosen for both symbolic and strategic reasons. In addition to the symbolism of the site as the place where Antigonus was defeated in 40 B.C., Herodium is near the border between Judaea and the southern, desert region of Idumaea, the homeland of Herod’s father, Antipater. The strategic importance to Herod of Idumaea, and the south, prompted his refurbishment of various sanctuaries there, the most important being the structure that covers the Tomb of the Patriarchs at Hebron, the traditional resting place of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The south is also associated with Esau, brother of Jacob and patriarch of the Edomites (who gave their name to Idumaea).

Herodium conveniently straddled both the symbolic south, and the north, where Jerusalem was located. Offering seclusion while being only seven miles from Jerusalem, the site was close enough that Herod could keep an eye on the ongoing works while managing the affairs of state.

(How did Jesus' final days unfold? Scholars are still debating.)

Rebel stronghold

Herod’s last years were marked by a protracted and agonizing illness, which according to Josephus was characterized by intense itching, severe intestinal pain, shortness of breath, convulsions, and gangrene in the genitals. Poor health as well as family conspiracies, murders, and riots stoked the king’s psychological instability. Josephus writes how Herod ordered 300 high-profile Jewish figures to be locked inside the hippodrome at Jericho and executed as soon as he passed away (Herod’s children stepped in to prevent the order from being carried out).

Herod died in 4 B.C. not at Herodium but at his winter palace in Jericho. Josephus gave a detailed description of what happened to the king’s body after his death: “A diadem was put upon his head, and a scepter in his right hand ... and the body was carried two hundred furlongs, to Herodium, where he had given order to be buried.”

Herod was succeeded by his sons, Herod Archelaus (briefly appointed ruler of Judaea, Samaria, and Idumaea by the Romans) and the longer-reigning Herod Antipas, ruler of Galilee. Herod Antipas features prominently in the New Testament where his actions contribute to the executions of both Jesus and John the Baptist.

(The birth of John the Baptist was a miracle. Here’s why.)

In A.D. 66 the Jews rose against Roman occupation. Josephus describes this uprising with the freshness of a firsthand witness, having served as a general on the Jewish side. He recounts how the Jews expelled the Romans from Jerusalem until the city was retaken in August, A.D. 70, and the temple that Herod had done so much to beautify was destroyed.

Jewish rebels who had seized Herodium were finally overrun by Roman troops in A.D 71. Decades later, during the Bar Kokhba Revolt of A.D. 132-35, the fortress was again used as a rebel base against Rome. The lavish complex fell into ruins and the location of the site were forgotten.

Rediscovery

In the 15th century a scholar dubbed the remains of Herodium “Mount of the Franks” in the belief a crusader camp was once built there. It was known by this name until 1838, when the American scholar Edward Robinson was the first to identify it as the palace-fortress of Herod the Great. Archaeological excavations at Herodium did not begin until the 1960s. From 1972, they were directed by the Israeli scholar Ehud Netzer, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Intrigued by Josephus’ description of Herod’s burial, Netzer spent years searching for Herod’s tomb. In May 2007 he finally announced that he had uncovered what he believed to be the royal mausoleum containing three broken sarcophagi.

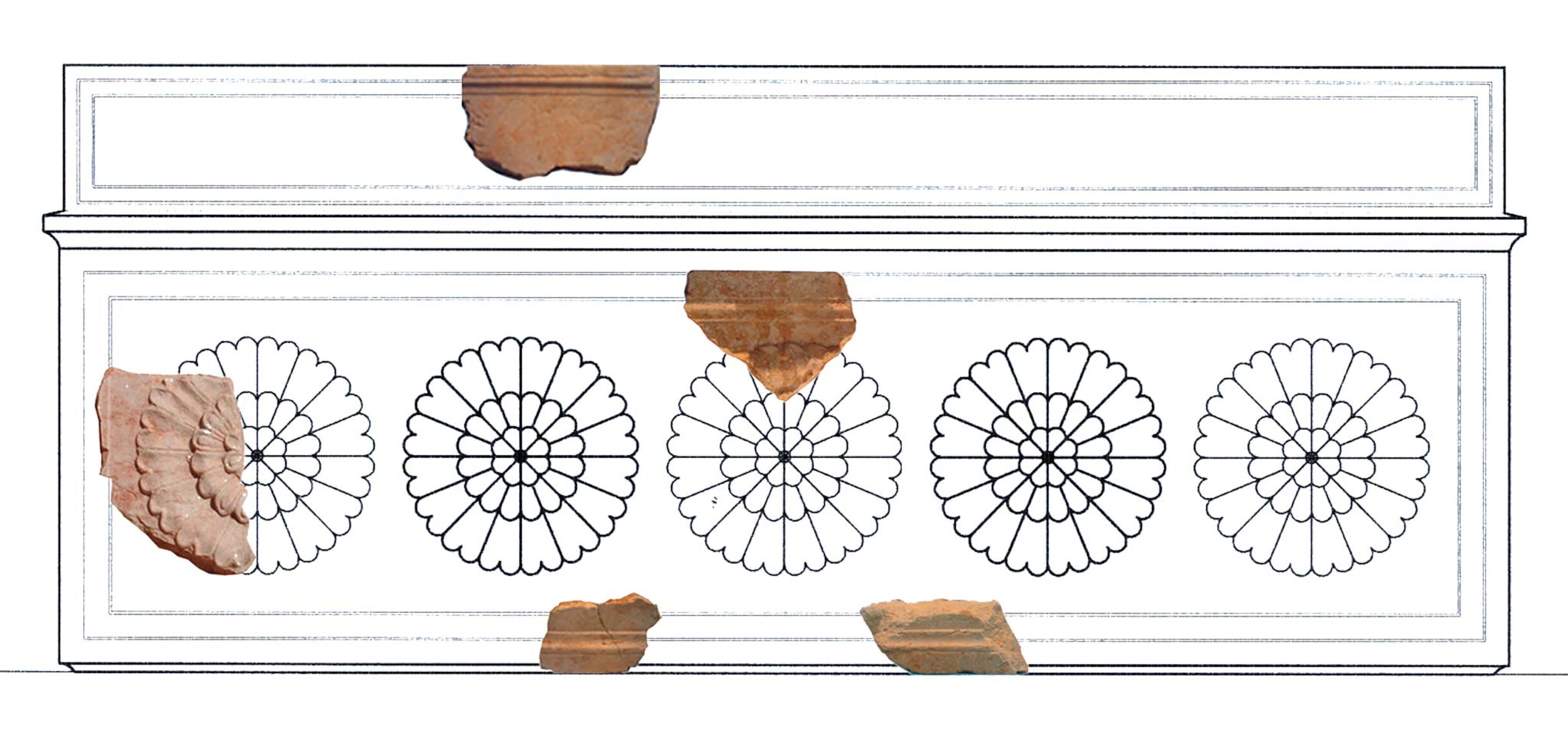

Built around 10 B.C., likely by the same workers who built the Temple of Jerusalem and Caesarea Maritima, the structure was located on the slopes of the hill, just a few feet below the palace-fortress. Once standing around 80 feet tall, the lower part consisted of a podium containing two rooms, one on top of the other. Above this was a tholos (a circular structure), surrounded by columns, the whole topped by a conical roof crowned with an urn.

(Who were the three kings in the Christmas story?)

The sarcophagus that is thought to have contained the remains of Herod is made of pinkish Jerusalem limestone. It had been smashed to pieces. The Jewish rebels that had occupied Herodium during the revolt of A.D. 66-70 considered Herod a puppet of the Roman emperor, so it is likely that they carried out the destruction.

The mausoleum, when intact, would have been much larger than others of the period and was probably designed to be visible from Jerusalem. Herod perhaps intended that other family members be buried there, too, which is probably why archaeologists have found two more sarcophagi next to the main one. They believe that one belonged to Malthace, a Samaritan woman who was one of Herod’s 10 wives, and mother of one of his successors, Herod Archelaus. Malthace died in Rome a few months after her husband. The other sarcophagus is believed to belong to Glaphyra, the second wife of Archelaus, who died in A.D. 7.

(Christianity struggled to grow—until this skeptic became a believer.)

Pieces of the puzzle

The fact that Herod wanted this site for his final resting place shows how significant it was to him. He could have chosen Jericho, his winter capital, where he had three palaces. But he preferred his tomb to be at Herodium, the scene of the victory that brought him his kingdom. Despite the desecration of his remains, and centuries of derision in both Jewish and Christian traditions, this palace-fortress, built on a man-made mountain, whose gardens were kept green in a desert, still has the power to awe its visitors.