Cixi, the controversial concubine who became queen, led China into the modern age

After Cixi seized power, the brilliant queen regent of China never let it go and guided her people into the 20th century.

Born in 1835, the girl who would gain fame as the Empress Dowager Cixi showed no obvious signs of future greatness. This girl, both through good fortune and unyielding determination, would rise to power in China, becoming the Dowager Empress, ruling as the queen regent from 1861 until her death in 1908, one of the most turbulent periods in China’s history. With her iron will and shrewd mind, she helped transform China from a medieval society to a modern power on the global stage.

Few concrete records remain of Cixi’s life before age 16. She was Manchu, the ethnic minority in power since the 1600s, and her heritage kept her feet from being bound, a tradition of China’s ethnic majority, the Han. Her family were most likely government employees. She probably could read, write, draw, and sew. Some historians say her father sought her advice and valued her opinion as highly as he would a son’s.

A respected position in her birth family would not win Cixi respect in the outside world. Because she was born female, her opinions meant little to men. Like other teenage girls at that time, 16-year-old Cixi had to be presented by her family to be considered as a concubine to the newly crowned Chinese emperor, Xianfeng. Selected as a low-ranking consort, Cixi left her family to live in the Forbidden City with the other women in the emperor’s harem. (See also: Beijing's Forbidden City built on ice roads.)

Xianfeng’s chief consort was Empress Zhen. The highest ranking of his wives, she became friends with Cixi. The relationship served them both well, especially after Cixi gave birth to the emperor’s only surviving son in 1856, an event that raised her status and provided her with the keys to power.

The Widows’ Coup

Early in his reign, Xianfeng faced colossal problems on both domestic and foreign fronts. He came to power at age 18 in 1850, the same year that widespread famine caused the Taiping Rebellion, a massive peasant uprising in the southern provinces. This insurrection would continue unabated and leave a third of China under rebel control. Six years later, France and Britain invaded China, beginning the second Opium War and putting an enormous strain on the country’s resources. This conflict also stirred up heated debates between pro- and anti-Western factions within China.

In the face of all this turmoil, Emperor Xianfeng died in 1861, and Cixi’s five-year-old son became the imperial heir, dubbed Emperor Tongzhi. Before his death, Xianfeng had selected eight men—princes and ministers from his inner circle—to form a Board of Regents and rule until his son came of age.

Cixi saw the emperor’s death as a necessary moment to strike a blow to improve China. She thought the regents had poorly advised the emperor. Cixi, then known then as Concubine Yi, worked together with Zhen on a plan to launch a coup. She and Zhen were supported by two of Xianfeng’s brothers, Prince Gong—an advocate of appeasing the West—and Prince Chun, who had married Yi’s younger sister. The two women successfully overthrew the regents, imprisoning five of them, executing one, and ordering two to commit suicide. The dowager empresses would rule until the child emperor came of age. They took new names: Zhen became Ci’an (“kindly and serene”); and Yi took the name Cixi (“kindly and joyous”) to mark the events.

The Queen’s Man

In imperial China eunuchs were a ubiquitous presence in the Forbidden City and had been serving as guardians of the emperor’s most inner court for more than 2,000 years. In Cixi’s time, one of the most influential eunuchs at court was Li Lianying, who was in charge of a staff of thousands: cooks, gardeners, servants, cleaners, painters, and other eunuchs.

Modernity and Tradition

Over the next five decades, China’s fate was determined by Cixi. She managed to impose her authority in spite of the inferior position the strict court protocol gave to women: The widowed empress presided over meetings from behind a screen, as the ministers were not supposed to see her. She never entered the foremost section of the Forbidden City, which was reserved for the emperor. Instead she relied on loyal men to carry out her decisions, such as Prince Gong, who headed the Great Imperial Council. Since she governed behind the scenes, her achievements were attributed to others, while her opponents cast her as a crafty, bloodthirsty conspirator.

Manchu governors (who dominated the Han ethnic majority) were divided between those who opposed the Westerners and those who, like Cixi, wanted to modernize China to boost its economy in order to avoid total submission to the West, as well as Japan, which had become a serious threat to China.

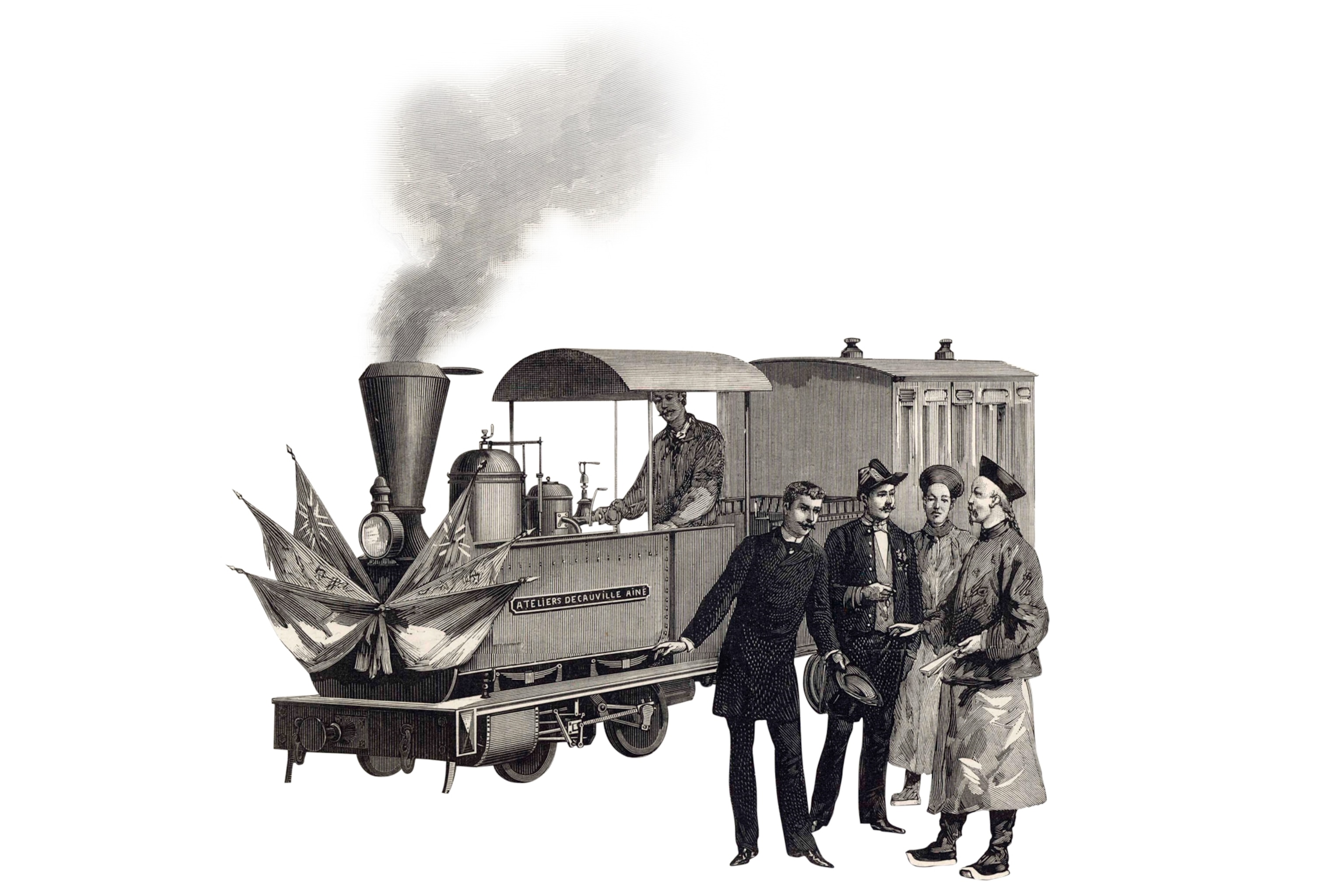

Cixi advocated westernization—but not completely. For example, she took nearly 20 years to allow the complete construction of a railroad because she did not want to disturb ancestral tombs that lay near the proposed line. She did not want to promote textile factories because they took work away from Chinese women. She also knew there was much opposition to reform among the people, from commoners to civil servants to nobles, who detested so-called barbarian Western customs.

Cixi presided over meetings from behind a screen, as her ministers were not supposed to see her.

In spite of the criticism, Cixi managed to bring peace to the country, put public finances on a sound footing, built a navy, and encouraged the country to open up to the world. With the help of the Westerners who commanded the army, the southern Taiping rebels were finally crushed.

Working on the Railroad

Although Cixi favored modernization, local opinion had to be respected. China’s first railroad, built in 1876 by the British, was dismantled after serious local protests. It took 13 years for Cixi to change enough minds to launch China’s first rail line, the Beijing-Wuhan railway. She felt it would be a “key component of our blueprint for Making China Strong.”

Officially, Cixi had to stand down when Tongzhi came of age in 1873. Two years into his rule, a bout with smallpox killed the young emperor, who left no heir. Some believed that power-hungry Cixi had poisoned her son to cling to power, but no proof for murder exists. Dark rumors circulated around Cixi, and not for the last time.

The Taming of the Emperor

Cixi again seized the reins of government, adopting the son of her sister and Prince Chun and naming him emperor. Ci’an and Cixi would continue to act as regents to the new emperor, Guangxu—who was barely three years old—until Ci’an’s sudden death in 1881. After that, Cixi was the sole regent. She embarked on a second wave of modernization, introducing electricity and coal mining. She started a war with France to oppose its territorial ambitions on the border between China and Vietnam, which ended in a stalemate.

Cixi officially ceded power to Guangxu in 1889 when he came of age. Educated in the strictest of Confucian orthodoxy, Guangxu was suspicious of everything Western. His failure to comprehend the modern world later led him to abandon China’s naval program, resulting in a crushing defeat to Japan in 1895, a crisis that made Cixi the de facto ruler again.

The tension between Cixi and her adopted son, and between reformers and traditionalists, was heightened by the influence of an academic and adviser, Kang Youwei. His reform proposals won over Guangxu, but Cixi mistrusted him. Kang involved the emperor in a plot to assassinate her, but their plans were discovered in 1898. Kang fled to Japan, and Guangxu was placed under house arrest, leaving him as a puppet but effectively removing him from power.

Cixi continued to rule China until her death. She survived a number of crises, including the Boxer Rebellion, which ended in a defeat for China at the hands of a foreign coalition in 1901. In the face of defeat, the ruling Chinese elite rallied around the dowager empress, who had published the unprecedented Decree of Self-reproach, in which she blamed herself for the devastation caused by the war. In January 1902 Cixi announced a series of reforms that shook up all aspects of Chinese life. Marriages between Han and Manchu partners were legalized. Foot-binding, a custom long practiced on Han girls, was banned. Freedom of the press was expanded. In 1906 Cixi announced that China would be transformed into a constitutional monarchy with elections.

Cixi died in November 1908, only one day after Guangxu, whom many believe she had poisoned to ensure the weak sovereign would stay out of power. Cixi named her two-year-old great-nephew the heir and designated a new dowager empress to watch over the nation she brought into the modern age.

Timeline

1852

Cixi becomes a concubine of Emperor Xianfeng. She will give birth to his heir Tongzhi in 1856.

1861

Cixi and Zhen, the emperor’s widows, seize power in a coup after Xianfeng dies. Tongzhi inherits the throne.

1875

After Tongzhi's death, Cixi appoints her adopted three-year-old son, Guangxu, as emperor and serves as regent.

1898

Cixi uncovers a plot to kill her orchestrated by Guangxu, whom she places under house arrest.

1908

Cixi poisons Guangxu, fearing he is too weak-willed to rule. Cixi dies a day later, having named a new heir.