How one catastrophic shipwreck sank a medieval dynasty

When a royal vessel sank of the coast of Normandy in 1120, it not only claimed hundreds of lives but also set off a succession crisis that changed England forever.

It should have been a fairly routine English Channel crossing for the boisterous and boozy crowd of young nobles aboard the White Ship—a party that included William Adelin, sole legitimate male heir to King Henry I of England.

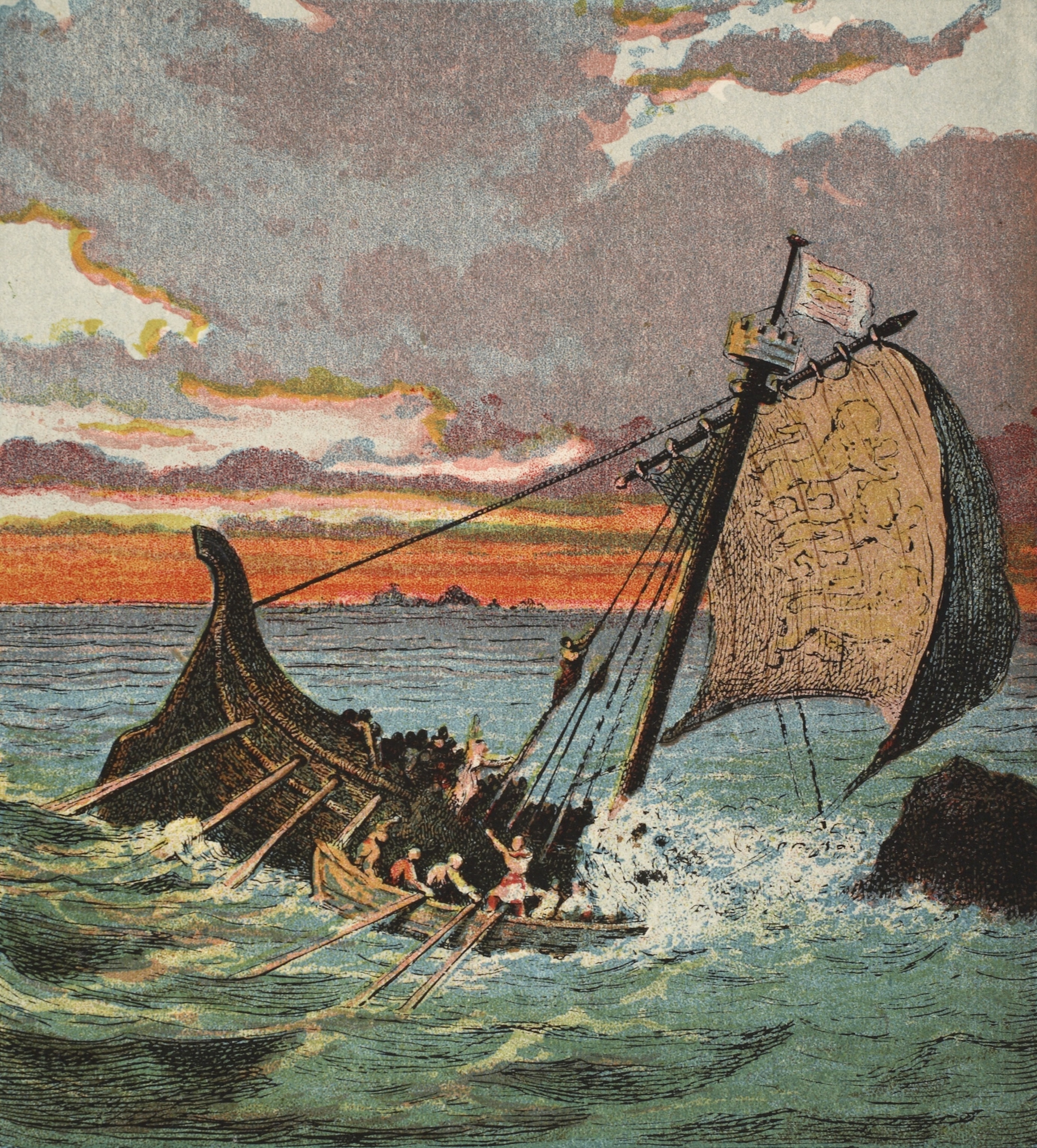

Only it all went horribly wrong as the ship embarked from Barfleur, in present day France, on November 25, 1120. The crew rowed right onto a rock, the White Ship sank, and around 300 people plunged into the icy water. Nearly every one of them died, causing violent consequences for England and exposing the fragility of a political regime built on hereditary succession.

“It is a nightmare scenario,” says University of Miami professor Hugh Thomas, who specializes in the history of medieval England and wrote The Norman Conquest: England after William the Conqueror.

The White Ship disaster was England's grim sequel to the Norman Conquest of 1066, a bloody affair that created a new political order in England with William the Conqueror and his son Henry I at the top. And the shipwreck showed just how quickly power could slip from a dynasty’s grasp.

(The Bayeux Tapestry was medieval propaganda for William the Conqueror.)

The shipwreck that altered a dynasty

Crisscrossing the Channel was a necessity for members of the Anglo-Norman elite like those aboard the White Ship. Their holdings and power straddled the unstable North Atlantic waters after William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, seized control of the English throne in 1066. The resulting regime stretched across England and a considerable chunk of what’s now France. By 1120, William the Conqueror’s youngest son, Henry, had a comfortable grip on power with his own 17-year-old son and heir William Adelin waiting in the wings. Their dynasty seemed secure.

Until the White Ship disaster. The most extensive account comes from a monk named OrdericVitalis, written several years later as part of a larger account of Norman history. (His sourcing is murky, but seems to have included a butcher, whom Vitalis identifies as the lone survivor.) Vitalis writes that a captain named Thomas FitzStephen pitched himself to Henry I as the man to sail the king across the Channel, claiming his grandfather carried William the Conqueror across on the voyage that won him the throne. King Henry declined, but gave him the job of transporting William Adelin and his entourage, including two of Adelin’s half-siblings.

Nobles and sailors alike started drinking, and some accounts say they dared to catch up to King Henry’s ship. The accident, accounts agree, was sheer recklessness. And it was a shocking loss of life: “Even in a period when sudden death is pretty common, to lose that many high-ranking people in one drunken accident is pretty devastating,” explains Thomas.

(How is France moving the Bayeux Tapestry? Very carefully.)

Why the White Ship’s sinking was so shocking

Such a disaster posed frightening questions for the people of the time: “Any event of this magnitude could only be interpreted through the lens of divine disfavor,” says Fordham University professor Nicholas Paul, who studies the political culture of the Middle Ages. “This was God striking a blow in some sense against the Anglo-Norman dynasty. How do you recover from that, and how do you correctly interpret such an action?”

Shipwrecks made it nearly impossible to recover victims’ bodies, which complicated succession and inheritance. What if a victim resurfaced alive and well? Or somebody posed as a victim? “It’s easier to understand, in some ways, that a dynastic regime relies upon childbirth,” says Paul. “But it also relies upon clear death.”

Even worse for medieval Christians, it created problems for the afterlife. According to their beliefs, “in order for you to be freed from the great pain and tribulation of Purgatory, you have to receive intercessory prayer from living people,” explains Paul. That required knowing the anniversary of their death, and it generally required a body. “Without those two things, you introduce this really hellish possibility that members of your family, the people in whom the political future is entrusted, are effectively in Hell.”

Yet the consequences extended far beyond the immediate loss of life.

Political consequences of the White Ship Disaster

The whole system of hereditary monarchy at the time relied on a visible king with the right pedigree; producing and raising the heir was a crucial and nonnegotiable part of the job to ensure political stability. “Everything comes down to human bodies,” says Paul. “Because you can never guarantee that you know exactly what’s going to happen to a body, that means it’s deeply uncertain and insecure.”

A combination of biology and bad luck could all too easily create a full-blown succession crisis, with contenders brutally battling it out for control and dragging the entire country into the violence. Which is precisely what happened to the House of Normandy.

While Henry I had numerous illegitimate children, William Adelin had been his only legitimate male heir, making his presumed death a political problem of the highest order. King Henry, who was in his 50s, remarried shortly after the White Ship disaster, as William’s mother was dead. But he produced no new heir, and so he chose his daughter Matilda as his successor.

(Who was Empress Matilda? The forgotten woman who nearly became England's first queen.)

But as this was a patriarchal society, ultimately, a man thought he could do better—Matilda’s first cousin, Stephen of Blois, who stepped up to challenge the succession.

Ironically, Stephen of Blois had initially planned to board the White Ship. He stayed behind, explains Thomas, saved by history’s best-timed case of diarrhea. When Henry I died in 1135, Stephen darted across the English Channel and usurped the throne by arranging to have himself crowned before the heavily pregnant Matilda could reach England in time, says Thomas. (This dramatic turn of events inspired George R.R. Martin’s HBO TV show House of the Dragon.)

The country was plunged into years of political tumult and violent civil war, known as The Anarchy. “It’s lots of local warfare, with raiding and burning and plundering—it’s just part of medieval warfare,” says Thomas. The turmoil ended only when Stephen agreed to accept Matilda’s son Henry as his own heir in 1153. Henry II succeeded Stephen in 1154.

Orderic Vitalis produced his account at some point in the midst of this turmoil, and Paul points out that he draws a stark parallel between William the Conqueror’s triumphant crossing of the English Channel and the disastrous failure of the White Ship.

“This entire regnum is created by one successful voyage—and maybe it’ll be undone completely by another, unsuccessful voyage,” says Paul.