These 5 explorers disappeared into thin air. Will we ever know the truth?

From Amelia Earhart to Percy Fawcett’s expedition to the Lost City of Z, the fate of these five explorers remains mysterious.

Western history is full of the daring feats of explorers—Lewis and Clark in North America, John Cabot in Canada, Marco Polo along the Silk Road, and the list goes on. But what about the explorers who set out with the same optimism as these navigational celebrities, only to face mysterious adversity? Here are five explorers who had all the advantages of their more successful counterparts, only not to reach their goals and leave very little trace of their true fates.

(This Arctic murder mystery remains unsolved after 150 years.)

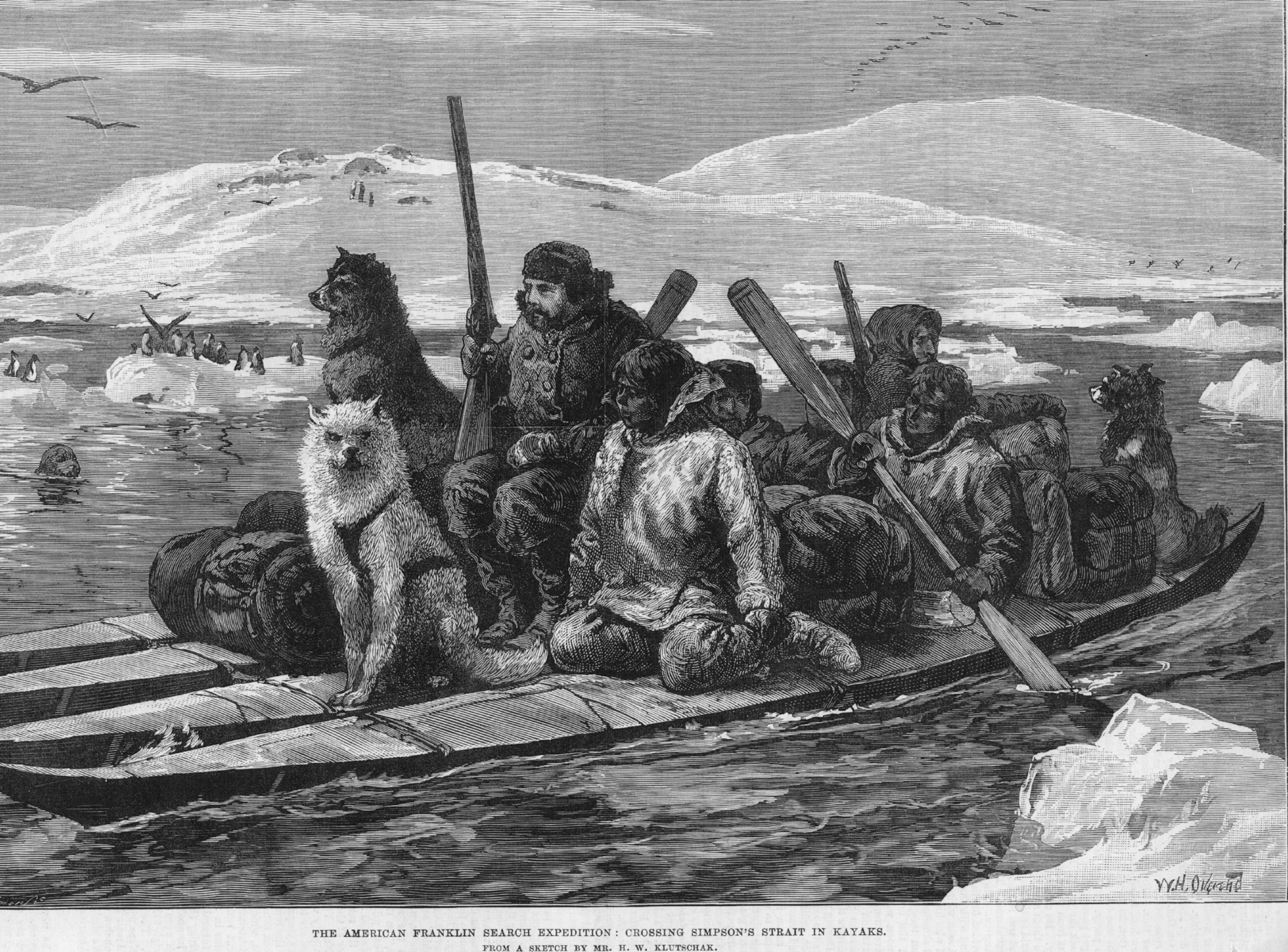

Franklin’s failed Northwest Passage quest

British explorer Sir John Franklin left England in 1845 with 129 crew members and officers in search of the Northwest Passage, a shipping route from the Atlantic to the Pacific through Canada. They were expertly equipped with iron-sheathed ships, three years of food and drink, even an early daguerreotype camera. Instead of finding the passage, however, the ships became trapped in the Canadian Arctic’s most treacherous, ice-choked corner, north of King William Island. Twenty-four men died by April 1848, including the captain. The new captain, Francis Crozier, apparently abandoned the ships and set out with the remaining crew over the icy terrain in a desperate attempt to reach land. Inuit hunters reported seeing bedraggled crewmen dragging sleds across the ice.

(In 1845 explorers sought the Northwest Passage—then vanished)

A few bodies have since been found, along with deserted campsites and bits and pieces, including silver dessert spoons and cotton shirt fragments. In 2014, the wreck of Erebus was located, followed by the Terror in 2016. While the wrecks themselves did not solve the mystery of what killed the men, the recovered bones of some men bore knife marks, suggesting the crew was fending off starvation by cannibalism.

(Arctic obsession drove explorers to seek the North Pole.)

Fawcett’s Lost City of Z

British explorer Col. Percy Harrison Fawcett already had undertaken several expeditions into the Amazon early in the 20th century when he came across an irresistible Portuguese document at the National Library of Brazil. Detailing the discovery of a “large, hidden, and very ancient city, without inhabitants, discovered in the year 1753,” it told of grand ruins hidden in the Mato Grosso jungle. Fawcett instantly decided to find the ruins, which he named the Lost City of Z.

After one failed attempt to find this awesome site, Fawcett, his son Jack, his son’s friend Raleigh Rimell, and two local laborers departed into the Brazilian wilderness in April 1925. They wrote their last dispatch home on May 20. Their Brazilian helpers had left them, Fawcett noted, but “You need have no fear of failure.” No one ever heard from the party again.

(These four lost cities were jewels of ancient Africa. What happened to them?)

Their disappearance became an obsession, with adventurers over the next decades trying to retrace their steps. A reporter who went after Fawcett in 1930 also disappeared, as did a Swiss hunter and his search party. Unconfirmed reports filtered out from the jungle of pale-skinned prisoners and their young children, but Fawcett and his party have never been found.

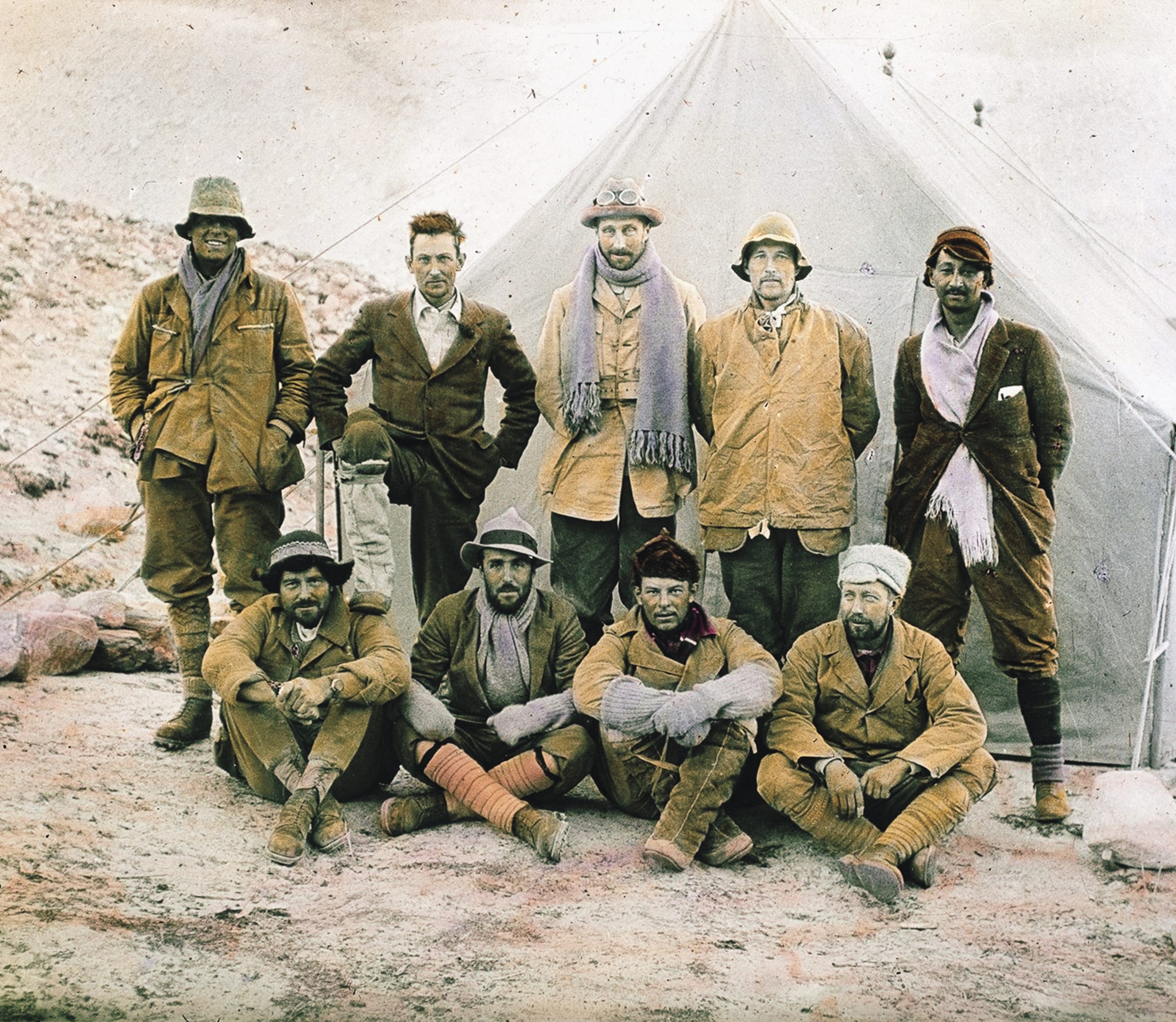

Mallory’s ill-fated Everest summit

The hopes of the world, or at least of the world’s mountain-climbing community, were pinned on George Leigh Mallory when he began his third attempt to reach the summit of Mount Everest in April 1924. The handsome English climber had reached 27,235 feet, 1,800 feet below Everest’s peak, on a 1922 expedition. This time, he intended to make it to the top.

On June 8, Mallory and his young companion, Sandy Irvine, set out on what they hoped would be the final sprint. A fellow climber spotted them, two black spots, about 800 vertical feet below the summit. Then a snow squall closed in, and the climbers disappeared.

Mallory’s body was not recovered for 75 years. In 1999, climber Conrad Anker discovered Mallory’s frozen corpse at 26,760 feet on the mountain’s north face. Irvine’s body has not been found.

Whether Mallory was on his way up to the summit or was coming down from a successful ascent is unknown. If he did reach the peak, he would have beaten Edmund Hillary, the New Zealand mountaineer who has been lauded for being the first man to reach the summit since his successful ascent in 1953. But the world may never know.

(Our team climbed Everest to try to solve its greatest mystery.)

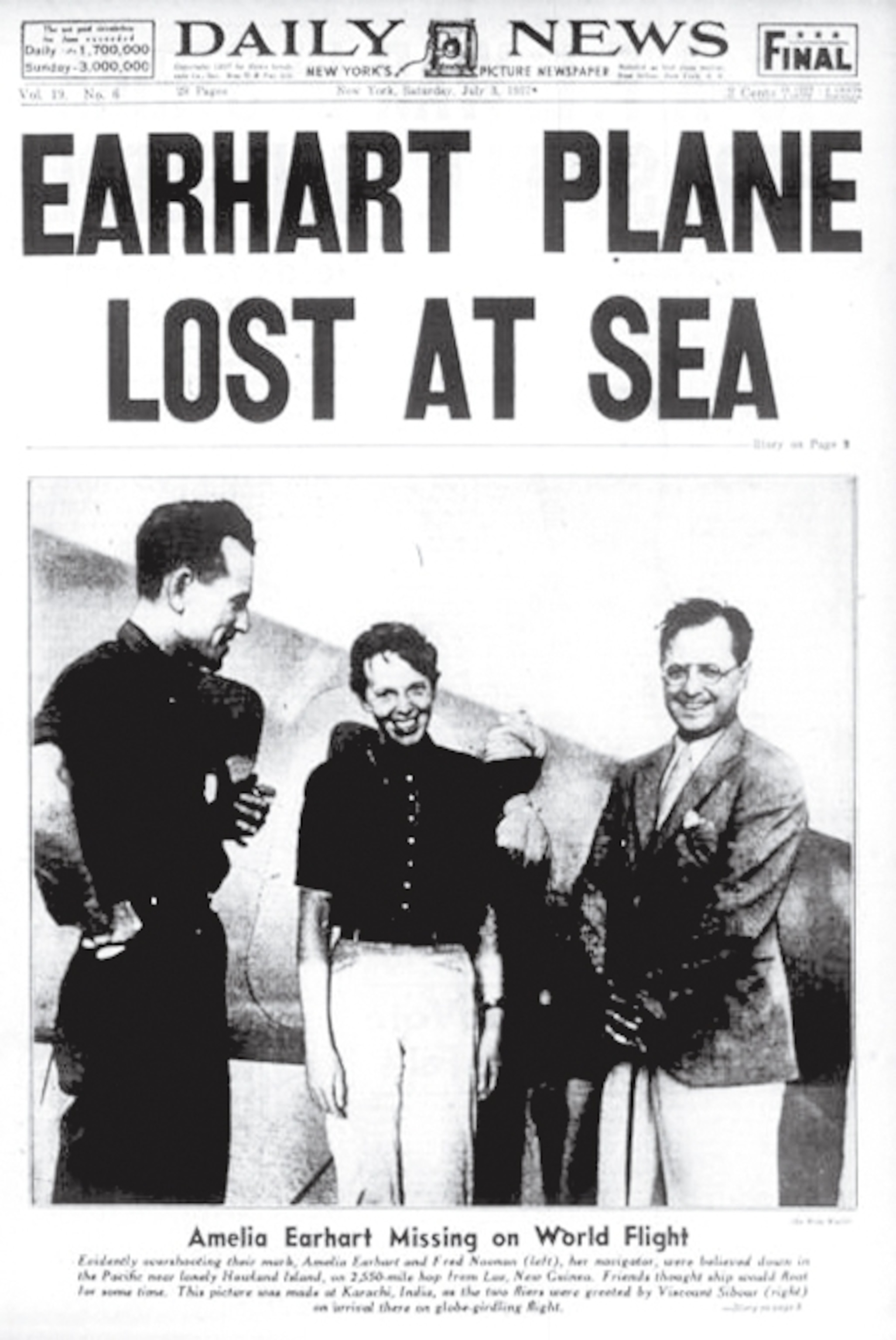

Amelia Earhart’s strange disappearance

Amelia Earhart was world famous; she was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic and the first person to fly from Hawaii to California. Her round-the-world flight in 1937 was her final challenge. Accompanying her when she took off from Miami on June 1, 1937, was an experienced navigator, Frederick Noonan. The first legs of the 29,000-mile trip were arduous, but the 2,556-mile Pacific leg from New Guinea to tiny Howland Island was the toughest of all. From the air, Earhart radioed she couldn’t see the island and was running low on fuel. Then silence.

(Remembering two icons in the search for Amelia Earhart.)

Recent forensic analysis suggest that bones found in 1940 on the Pacific island of Nikumaroro were those of the aviator. Dimensions of Earhart’s body according to photos and clothing matched measurements recorded of the bones. Unfortunately, the bones themselves were lost—so DNA testing cannot be done. Researchers are still following every lead, from a skull fragment found in a museum to underwater fragments possibly from her plane, but so far, her disappearance remains a mystery.

(Inside the search for Amelia Earhart’s airplane.)

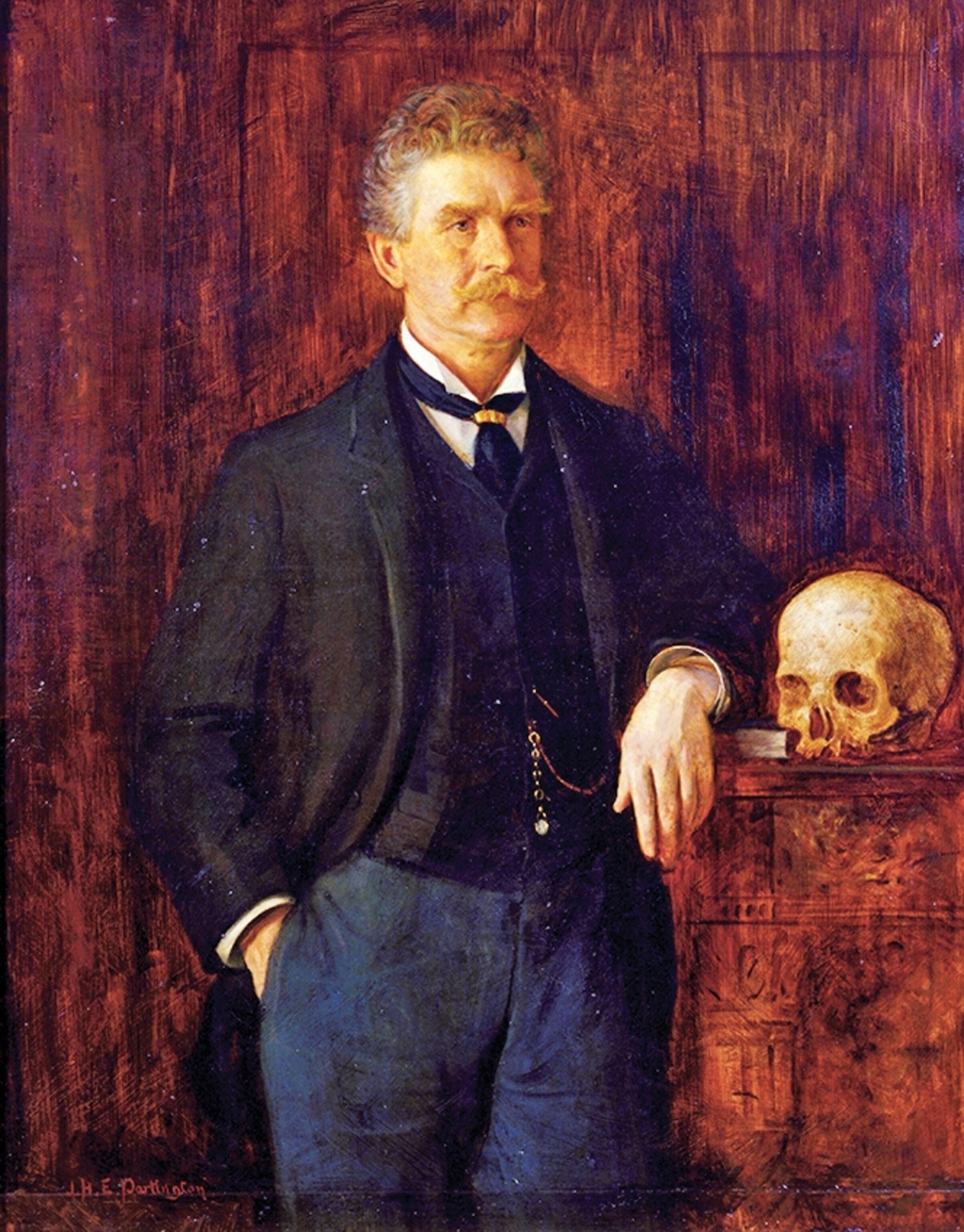

Ambrose Bierce’s baffling Mexican quest

Ambrose Bierce isn’t the typical explorer. A Civil War veteran, he also was a journalist and poet, known for his cynical and misanthropic writings. One such entry in his Devil’s Dictionary, for example, reads, “Fidelity: A virtue peculiar to those who are about to be betrayed.” In 1913, his family dead and his career waning, the 71-year-old Bierce headed out to visit Civil War battlefields, including Missionary Ridge and Chickamauga, and onward to Mexico. “I am going to Mexico with a pretty definite purpose which is not at all present disclosable,” he wrote to his secretary. He may have joined up with Pancho Villa’s rebel army and traveled with it to Chihuahua.

Reports from one of Villa’s battles told of an “old gringo” killed in the fighting. Could that have been Bierce? Or did he live on in Mexico, California, France, or Brazil, where reports have placed him over the years?

To learn more, check out 100 Greatest Mysteries Revealed. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.