Why this ancient 'King of the World' was so proud of his library

Ashurbanipal's military prowess was unquestionable, as his Assyrian Empire conquered lands from Egypt to Mesopotamia, but the mighty king crowed the loudest about his great royal library, the world's biggest in the seventh century B.C.

From inscriptions on palace walls and incisions in cuneiform tablets, he was styled “Great King, the Mighty King, King of Assyria, King of Sumer and Akkad, the King of the World.” Those titles might seem exaggerated today, but for his time, they just might have been warranted. For almost 40 years, Ashurbanipal reigned over the Assyrian Empire and ruled over the largest kingdom of its time—and perhaps the greatest up to the seventh century B.C.

(Discovering Gilgamesh, the world’s first action hero.)

When trying to discuss Ashurbanipal’s greatness as a world leader, understanding what his contemporaries, the Assyrians, meant by “world” is vital. Their world was Mesopotamia, but Assyria’s holdings extended farther than that—from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, and from Egypt to the mountains of southeastern Turkey. The Assyrians were certainly aware that beyond lay other lands, peoples, tribes, and cities, but they referred to what was outside their realms as “empty lands:” territories of no interest, occupied by uncivilized people with nothing of value to offer.

The times of the late Assyrian Empire were tumultuous, violent, and even brutal. Ashurbanipal needed to exercise every talent, military and diplomatic, to hold that empire together, safe from those unknown hordes from the so-called empty lands.

Ashurbanipal was born sometime around 685 B.C., to King Esarhaddon and one of his three wives. When Ashurbanipal was 12 or 13, Esarhaddon began preparing for his succession. The eldest son died before reaching maturity. To avoid squabbling and palace intrigue, the king named both Ashurbanipal and his older half brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, as crown princes. He assigned Shamash-shum-ukin to rule the city of Babylon, which was under Assyrian control. Ashurbanipal stayed in the capital.

Crown prince Ashurbanipal was trained in military affairs, diplomacy, and administration. He was also tutored in history, literature, archery, hunting, and horsemanship. He mastered the teachings of the priests and scribes and learned to read Sumerian and Akkadian. Possibly by the intervention of the queen mother, his grandmother Naqi’a-Zakutu, he was given heavy responsibilities dealing with nobles and the royal court, controlled governmental appointments and supervised building projects within the Assyrian homeland, and even ran the imperial intelligence service.

His mastery of these responsibilities, his demonstrated statesmanship, and his detailed reports to his father led Esarhaddon to leave Ashurbanipal in charge of affairs when he left on a military expedition to Egypt. It was his last. Esarhaddon died in 669 B.C. at Harran. The relationships Ashurbanipal had forged with nobles and the military smoothed the transition of power to him after his father’s demise.

Brawn and brains

Ashurbanipal continued the fights of his father, and like many of his predecessors, he launched his own military campaigns to consolidate his position as king. Where he stood out was in the significance and scope of his military victories. He chalked up successful conquests: against Thebes, capital of Upper Egypt in 664 B.C., and against the Iranian kingdom of Elam at the Battle of Til-Tuba in 653 B.C. He put down a revolt by his brother Shamash-shum-ukin in Babylon in 648 B.C. and sacked the city of Susa in 647 B.C.

(The Bible depicts Babylon as doomed, but Nebuchadrezzar II restored it to glory.)

Ashurbanipal claimed in inscriptions that he was the most exceptional Assyrian king. Unlike most ancient leaders, his claim to greatness was not based solely on military prowess. While his victories are certainly featured—lands conquered and enemies subdued—Ashurbanipal boasted the most of his intellectual gifts: “I, Ashurbanipal, learned the wisdom of Nabu [the god of writing], laid hold of scribal practices of all the experts, as many as there are.”

Inscriptions refer to his ability to interpret ancient texts, solve complex mathematical problems, and debate theological questions with his court’s most renowned sages and soothsayers. In one text Ashurbanipal styles himself as a disciple of Adapa, the first of the seven Mesopotamian sages, endowed with intelligence by Ea, god of wisdom. The legendary Adapa lived before the ancient flood that, according to Babylonian myth, had devastated the cities of Mesopotamia.

Despite Adapa’s omniscience, he never acquired divine status because he refused to accept the bread and water of eternal life offered to him by Anu the sky god. Because of his refusal, Adapa and all humanity remained mortal. Linking himself to Adapa, a figure central to Assyrian founding myths, Ashurbanipal aligned himself with Assyria’s revered ancestors and emphasized his skills at deciphering ancient Sumerian tablets.

Assyria's most learned king

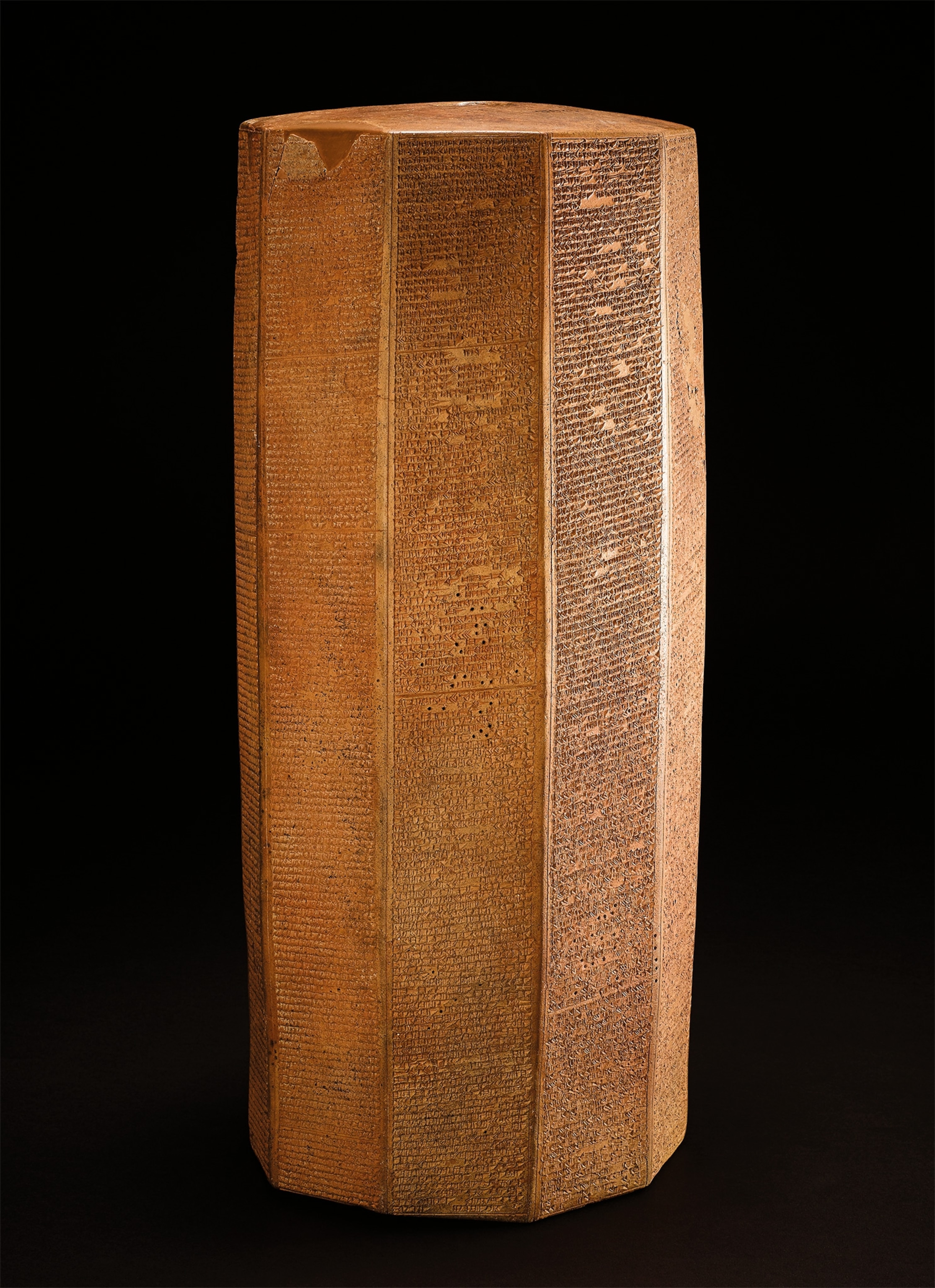

I learnt the lore of the wise sage Adapa, the hidden secret of all scribal art. I can recognize celestial and terrestrial omens (and) discuss (them) in the assembly of the scholars. I can deliberate upon (the series) “(If) the liver is a mirror (image) of heaven” with able experts in oil divination. I can solve complicated multiplications and divisions which do not have an (obvious) solution. I have studied elaborate composition(s) in obscure Sumerian (and) Akkadian which are difficult to get right. I have inspected cuneiform sign(s) on stones from before the flood.

Borrowed books

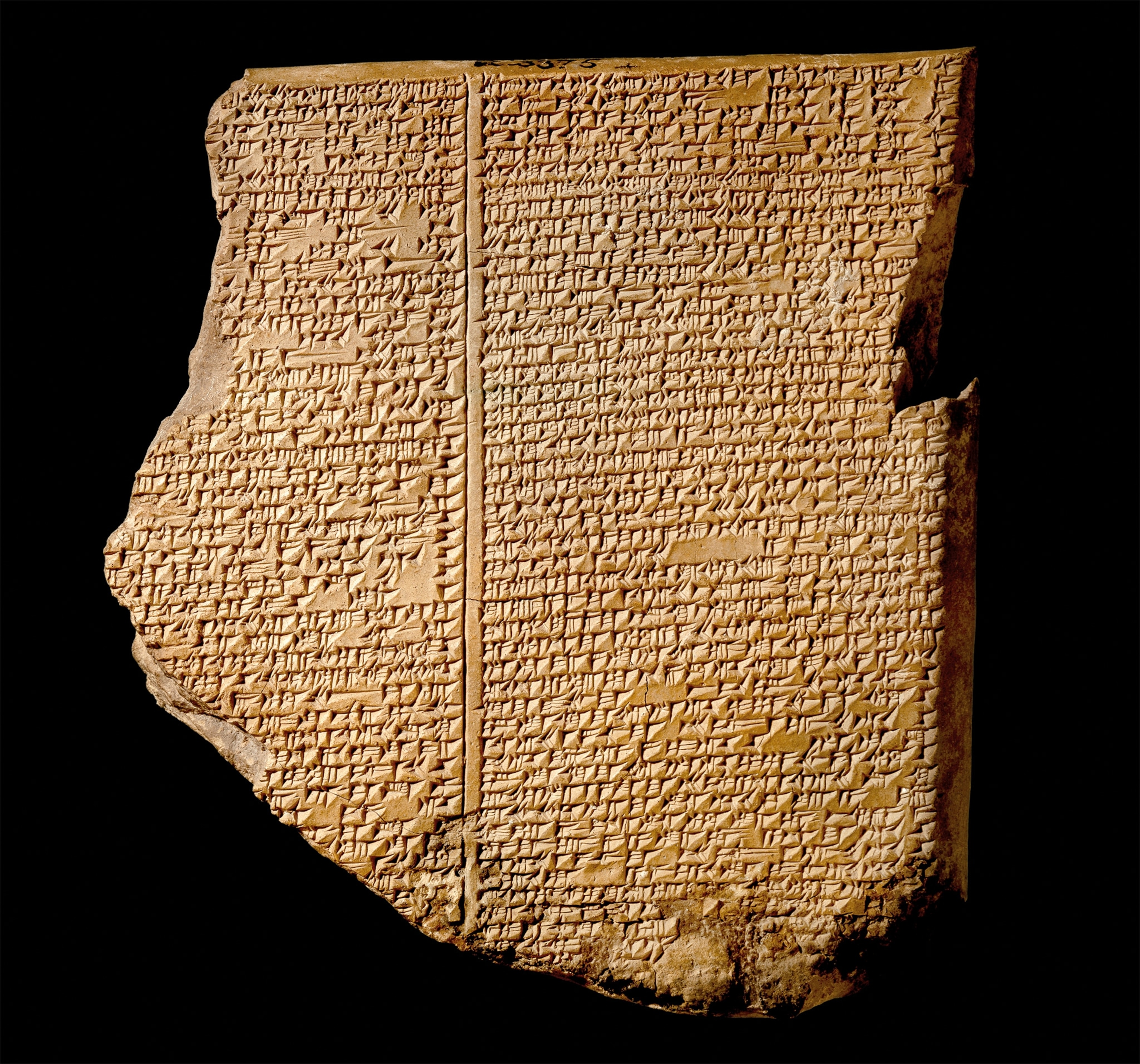

Ever keen to present himself as an intellectual, Ashurbanipal set out to create what became his most important legacy: the great royal library at Nineveh. There he gathered the records of Mesopotamian knowledge, from literary texts to medicine, magic, and divination.

(The true location of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon remains an unsolved mystery.)

The process of building up the Assyrian library was long and complex. The king ordered his officials to seize the holdings of all the libraries of Assyria and Babylon. In this way, he acquired the private library of Nabu-zuqup-kenu, former scribe of Sargon II and Sennacherib, which included a large collection of divination texts based on astronomical and meteorological observations.

It was more difficult to raid the Babylonian libraries than the Assyrian ones since the collections in Babylon were closely guarded by scribes and priests in the temples. When the relationship between Ashurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, crown prince of Babylon, was amicable, Ashurbanipal asked Babylonian sages for copies of the most important texts in their keeping. However, after the Babylonian revolt of 652 B.C., Ashurbanipal’s policy became much more aggressive, and he simply confiscated documents at will. There is evidence that in 647 B.C., when the Babylonian revolt had already been put down, 1,469 cuneiform tablets were added to the Nineveh library, brought directly from Babylon.

Ashurbanipal devoted much time and attention to creating his library. Sometimes he supervised the copying process in person, even suggesting modifications according to his taste. This policy ran counter to scribal practice; texts were thought to contain ancient knowledge imparted by the gods or sages from former times, so temple scribes were scrupulous about not making changes. Ashurbanipal’s choice to break that rule shows that he considered himself worthy of a place among the elevated group of the seven sages.

Future in the stars

King's palace

Another of Ashurbanipal’s greatest legacies was the construction of what is now known as the North Palace of Nineveh, erected between 646 and 644 B.C. The momentous building project was made possible largely thanks to the loot and material resources captured in Assyria’s decisive victories over Elam and Babylon. The North Palace stood raised on a large terrace around 20 feet high, next to the temple of Ishtar, a goddess whom Ashurbanipal asked to protect his new residence. Hundreds of laborers and conscripts, including many prisoners of war, were put to work on the palace under the orders of the king.

("Extremely rare" Assyrian carvings discovered in Iraq.)

Like the vast majority of Assyrian buildings, the North Palace was built of mud brick, so little remains of the original structure. Fortunately, though, the buildings were decorated with stone bas-reliefs, many of which have survived. Their artistry and the depth of their detail yield valuable insights into the life and personality of the Assyrian king.

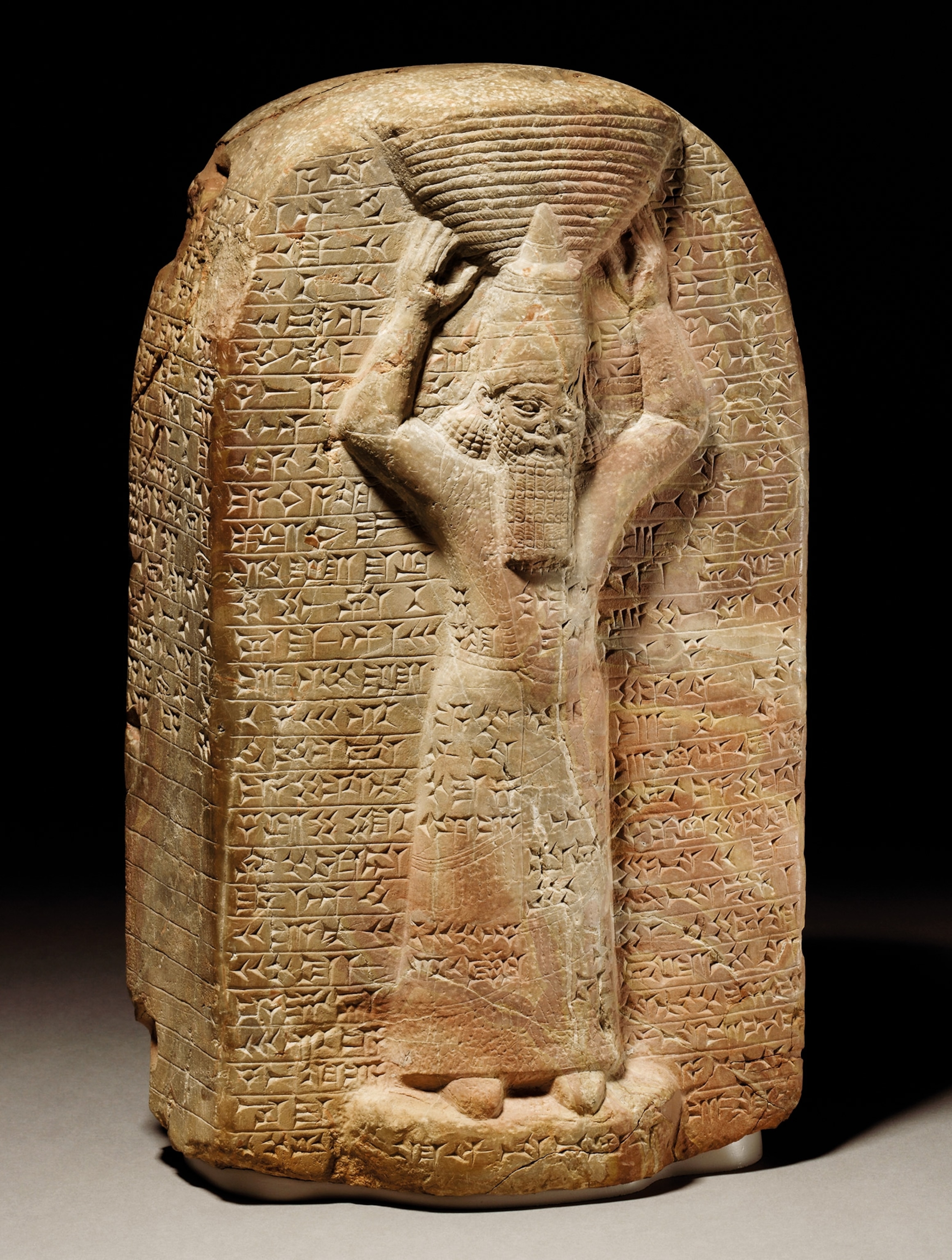

Ashurbanipal sought magical protection for his lavish palace to keep evil spirits at bay; the practice was nothing new. His grandfather Sennacherib and great grandfather Sargon II had entrusted the work of protection to the lamassu, colossal bulls and winged lions with human heads. But Ashurbanipal dispensed with these impressive creatures, turning instead to representations of the Sebetti, powerful protective spirits from Mesopotamian mythology, to guard his throne room.

Many of the reliefs in the throne room depicted battle scenes, commemorating Ashurbanipal’s great military victories, including the campaigns against Babylon, Elam, Egypt, and the Arab tribes. Although Ashurbanipal rarely accompanied his soldiers onto the battlefield, he created a powerful iconography through these elaborate reliefs that would preserve a legacy as a great military leader.

In the palace’s private rooms, which few had access to, the king chose a slightly different emphasis for the reliefs. In these spaces the military-themed reliefs are mixed with scenes that depict the king celebrating his triumphs. One panel shows Ashurbanipal performing a ritual libation using the severed head of the Elamite king Teumman, whom he defeated at the Battle of Til-Tuba (the defeated king’s head was also paraded through the streets of Nineveh). These images of military victories and triumphal celebrations seem contrived to send visitors a clear message of the price paid by those who dared to resist Assyrian power.

Royal pride

Perhaps the most famous pieces of art from the North Palace are the reliefs of a lion hunt, the sport of kings in ancient Assyria. Rendered in a striking, lifelike manner, Ashurbanipal and his retinue kill multiple lions, whose painful deaths are shown in gruesome detail.

(Age-old secrets revealed from the world's first metropolises.)

King’s lament

Ashurbanipal assumed the throne when he was only 16 and ruled for 38 years. He presided over many campaigns from the Nile to the Persian Gulf. Most often he stayed in Nineveh, keeping watch over the empire’s administrative machinery and dealing with palace intrigues, while his generals conducted his wars.

As Ashurbanipal ages, his writings change. On the last tablet known to be authored by him, he does not sound like the confident conqueror:

"I did well unto god and man, to dead and living. Why have sickness ... and misery ... befallen me? I cannot do away with the strife in my country and the dissensions in my family. Disturbing scandals oppress me always. Misery of mind and of flesh bow me down; with cries of woe I bring my days to an end. On the day of the city-god, the day of the festival, I am wretched; death is seizing hold of me, and bears me down."

Historians don’t know what maladies afflicted him as he aged. Some hypothesize that lingering effects from a hunting wound caught up with him or perhaps an illness left him vulnerable at age 54.

Protectors of the palace

The aging king clearly saw the signs that his empire, his life’s work, was beginning to crumble. Perhaps Ashurbanipal foresaw that southern Babylon, Palestine, Phoenicia, and Media would be the first in his empire to go, and that short-lived rulers would fail to stem the tide of rebellion and departure.

How he died is unknown; even the year is uncertain. In Lord Byron’s play Sardanapalus (Greek for Ashurbanipal), the king sets his palace afire and perishes in the flames. That story is most likely legend since that is how Ashurbanipal’s brother Shamash-shum-ukin died when Ashurbanipal’s troops took over Babylon.

Barely a decade after his death, the Assyrians would find themselves hemmed in their Mesopotamian homeland. Not long after, the great city of Nineveh itself would fall and be laid to waste. Two hundred years later, Xenophon would march his mercenary army where Nineveh once stood, but absolutely no trace of Ashurbanipal’s capital remained for his soldiers to trample underfoot.