What happens if the flu and RSV fuse into a single virus? Now we know.

For the first time, scientists have created a hybrid of the two seasonal viruses. Their discovery yielded a few surprises.

For the first time, scientists have shown that two seasonal respiratory viruses currently circulating in the United States—and overwhelming hospitals with sick kids—can form a hybrid virus under the right conditions. The finding, they say, is not a cause for worry—but it does provide some intriguing insights into how viruses learn new tricks.

The influenza A virus, which causes the most common flu, and the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are the leading causes of childhood infections. Both RSV and flu viruses circulate together every year in fall and winter and people frequently get infected with both viruses. Scientists had known that during co-infections, a hybrid combining genetic material from two virus types could form, but none has ever been detected.

A hybrid virus can be more infectious or can infect new parts of body; it can also be weaker than its parental viruses because of their evolutionary incompatibility. But the characteristics of potential influenza-RSV hybrid were unknown until scientists were able to create one in an experiment.

“This is an interesting demonstration of how viruses can socialize and interact together,” says Olivier Schwartz, a virologist at the Pasteur Institute, in Paris, France.

Sharing genes

Many viruses target the respiratory system of the body, and more than one kind of virus can be present in the body at the same time. One in five infants hospitalized for a respiratory tract infection, for example, is infected with two different viruses, providing an opportunity for viruses to share genes.

Hybrid viruses possessing combinations of different bits of viral genes, resulting from coinfections with two or more related viruses, have long been thought as an important step for virus evolution. For example, parts of the bovine coronaviruses may have originated from an influenza C type ancestor through such a mash-up.

“Viruses pick up genes from host cells and from each other,” says Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University Health at Shreveport. “We also get genes from viruses.” For example, a gene encoding a protein called syncytin, which is produced in the placenta, is thought to be a leftover from a virus that infected our mammalian ancestors, millions of years ago. But such exchanges of genes are rare and happen slowly in the evolutionary time scale.

It is difficult to observe the formation of a hybrid virus, such as the one between flu and RSV, because both viruses must be present in the same cell to form a hybrid. While more than one respiratory virus can infect the body, viruses compete for dominance at the individual cell level through a phenomenon called viral interference. This means that usually only one type of virus can infect a cell; and studies in mice have confirmed that RSV and influenza compete against each other to infect a cell and multiply. This competition makes the chance of a hybrid forming in nature even more unlikely. But not impossible.

Matchmaking to form a hybrid virus

To create the right conditions for two unrelated viruses to meet, scientists in the U.K. infected human lung cells in a dish in the laboratory with both influenza A and RSV viruses. “We observed quite a few cells that were coinfected with both viruses in them,” says Pablo Murcia, a virologist at University of Glasgow, UK, who led the study.

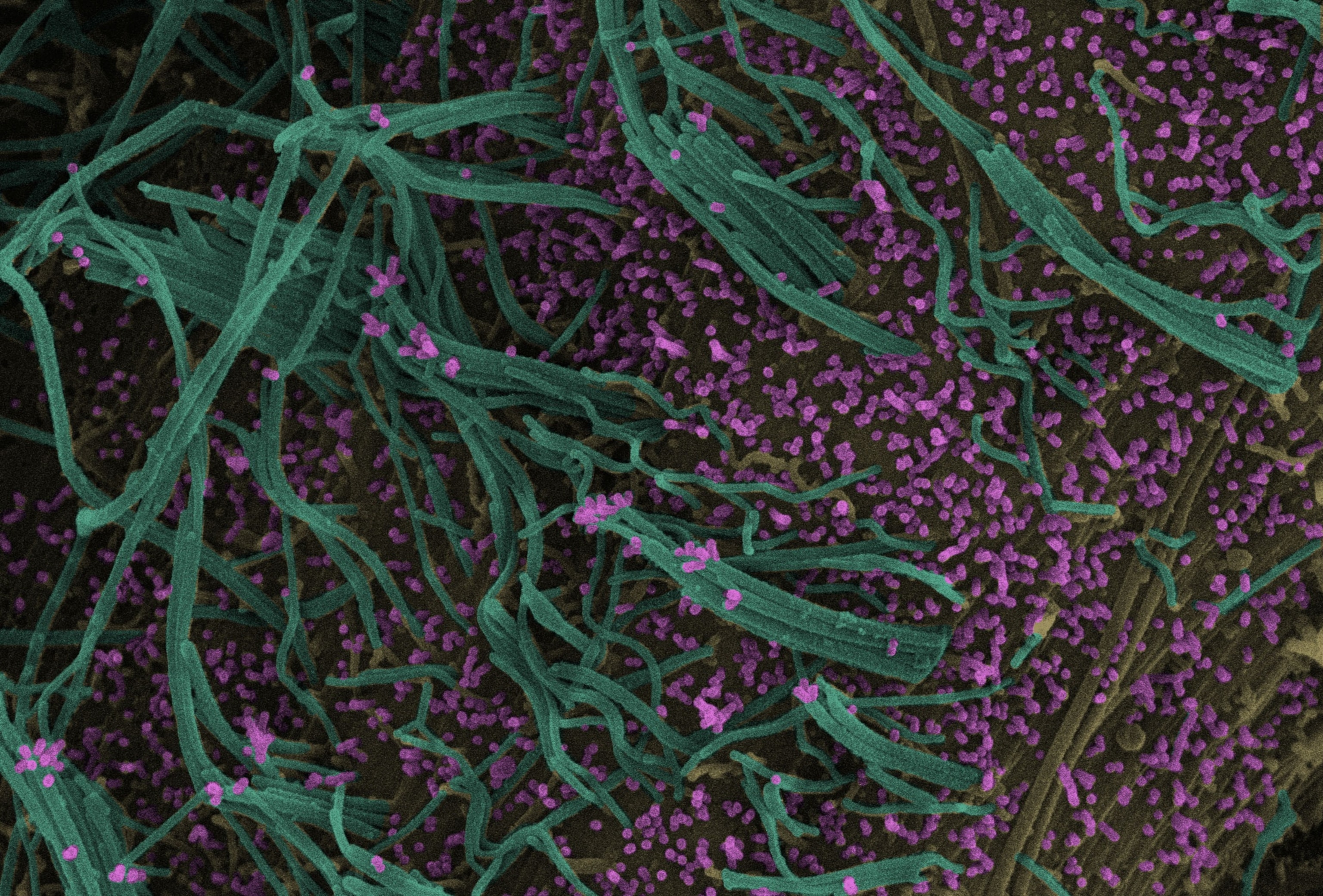

In these co-infected cells, flu and RSV viruses fused together to form a new bottle-shaped hybrid virus in which the RSV bit formed the base, and the flu virus bit formed the narrow neck.

“How lovely the evidence is, that you can put these two viruses in the same cell at the same time, and produce chimeric particles,” says Kamil.

The hybrid viruses were capable of infecting lower respiratory tract cells, not typically targeted by the flu virus. The hybrid virus was able to dodge flu antibodies, but antibodies against RSV effectively stopped the hybrid’s spread.

“Flu uses these hybrid particles as a sort of Trojan horse,” says Murcia, which allows them to infect cells in conditions that wouldn't be normal for the virus.

Is this hybrid a threat?

Murcia and Kamil are emphatic that generating the RSV-flu hybrid does not yield a new, more dangerous virus. “It's not scary, it's interesting and it's not necessarily surprising,” Kamil says.

Most people already have antibodies against RSV and flu after infections during their toddler years. So a hybrid virus between RSV and flu is unlikely to pose a threat by generating an immune escaping virus. Rather it is just like two viruses packaged in a single envelope, says Murcia.

Moreover, the hybrid virus has still only been shown to occur in a test tube in an artificial situation. “It shows an important virologic proof-of-concept that respiratory viruses can recombine,” says Dan Barouch, a virologist at the Harvard Medical School. But it is not known how often it can happen.

“Just because we're finding out about this now doesn't mean that it hasn't been happening already,” says Sarah Meskill, a pediatrician at Texas Children's Hospital, who specializes in treating viral respiratory illnesses. Meskill’s work has shown that co-infection of RSV and influenza does not warrant extra clinical attention. “It is definitely possible that RSV and flu have been making hybrids, but clinically, it doesn't seem to be relevant to the point where we need to act on it.”

For other viral diseases as well, coinfections do not increase the disease severity, although in some cases they may increase the chances of viral pneumonia.

“Future work is warranted to determine the importance and relevance of this process in infected humans,” Schwartz says. If the hybrid virus isn’t stable, or doesn’t provide a distinct immunological advantage, it won’t grow further, he adds.

However, even with a low possibility of a hybrid virus forming in a co-infected patient, the new study provides evidence for a pathway that viruses can use to learn how to infect different cells. For example, a flu-RSV hybrid can expand the range of cells the flu virus alone can infect—nose, throat, and windpipe—to also include lung cells which are typically the target of RSV.

“How often does that happen in nature? Probably not as often as we fear,” says Kamil. “But with billions of people, and animals on the planet, there's enough times that it may happen.”