A Chance Encounter Leads to a Deeper Understanding of a Civil War

What happens when lives are interrupted by war? What makes people decide that, rather than start over elsewhere, they’ll stay in a place with ghosts of the past both bitter and sweet, even if it means being alone or living in ruins?

These questions are the inspiration behind photographer Olga Ingurazova’s project “Scars of Independence,” which focuses on the aftermath of the 1992-93 civil war between the Republic of Georgia and the breakaway region of Abkhazia on the east coast of the Black Sea.

Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Abkhazia was an autonomous republic within Georgia and a popular travel destination for the Soviet elite. Following the Georgia’s independence, tensions surfaced as Abkhazian support for secession mounted.

The resulting war claimed thousands of lives and displaced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. Abkhazia ultimately claimed independence from Georgia, but the cost was high on both sides—not only in shattered lives and lost loved ones but also in terms of an international economic embargo that left the disputed territory in ruins.

While Abkhazians recognize themselves as belonging to a sovereign state, the UN and most of the international community still consider it to be part of Georgia. Their passports aren’t internationally recognized and they’re therefore restricted from travel abroad (though Russia, which formally recognized Abkhazia’s independence in 2008, has issued Russian passports in a controversial move).

Abkhazians remain in a sort of limbo, frozen in time while trying to build and maintain a national identity, says Ingurazova, who first traveled to Abkhazia in 2012 to embark on her first personal project. Hailing from Russia, she had seen her grandparent’s vacation pictures from years before but had never been to the territory herself. She was, as she confesses with a laugh, full of romantic notions about being a photojournalist documenting a place scarred by war.

But it wasn’t until an unexpected turn of events that she truly found her way into the story. On her second trip there, she underwent emergency surgery for internal abdominal bleeding. She feels lucky to have survived. Lying in a hospital bed far from home, she says, “My first desire was to leave this place immediately. But a week spent with other patients became the moment of reckoning. I realized that my traumatic experience was part of the everyday life for many locals who didn’t have any other choice. A sense of purpose was all that I had.” Ingurazova would come to find that almost everyone she met had experienced loss—of a loved one and of their livelihood—in a war that had been fought in close quarters. “They survive as they can,” she says.

She had been driven to the hospital by a man who lived near the place where she had been staying. Consumed with pain, she had not registered his face or who he was. She “met” him for the first time when he came to the hospital to check on her. On learning that she was alone and needed a place to convalesce—she was too ill to travel—he offered to let her stay with him.

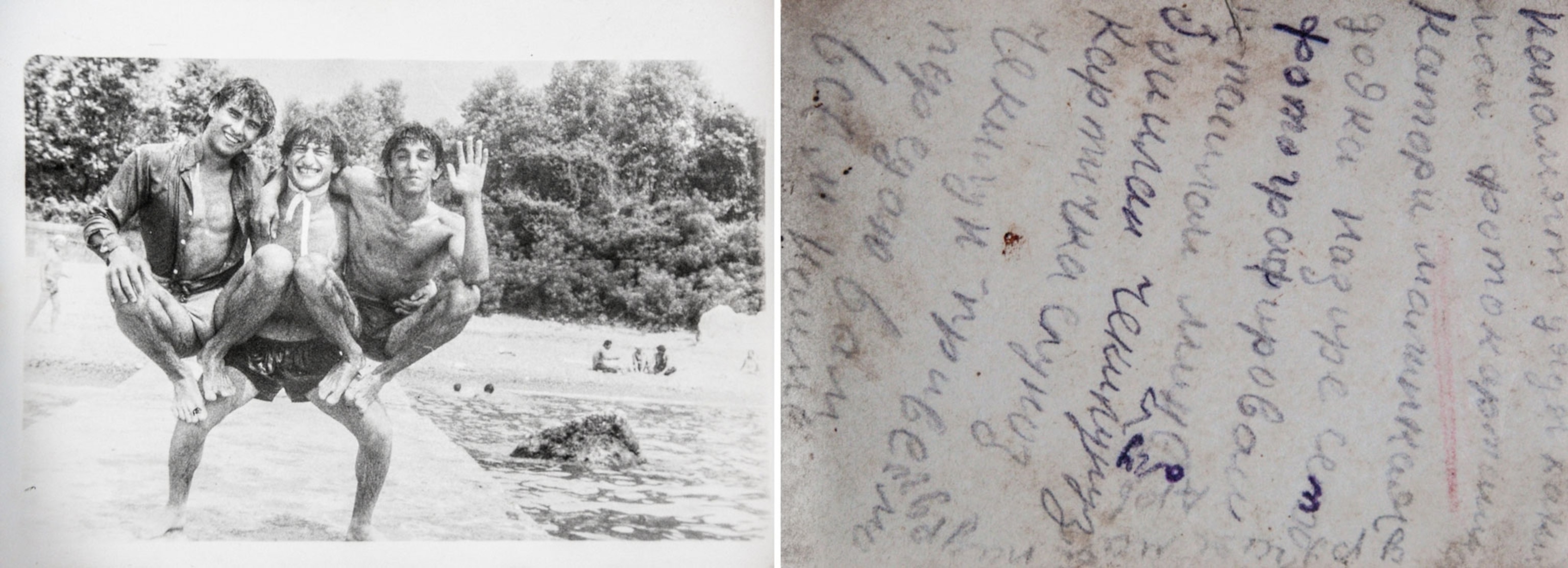

She took an enormous leap of faith, trusting her safety and well-being to a stranger who lived on an isolated mountain homestead. He nursed her back to health, and over the next three years, as Ingurazova returned to work on her project, they developed a friendship. Gradually he opened up to her about his own story, telling her things he had never shared before. She began to photograph him.

He calls himself Wolf, a nickname he was given during the war (it’s a symbol of the warrior in Caucasian mythology, says Ingurazova). His childhood—spent growing up in a large farming family in an economy bolstered by tourism—was a happy one. When the war broke out, he was 22 and the father of a newborn son. He joined the Abkhaz army the day after his sister was killed by an unguided Georgian missile, a move that would protect his brothers, as one son out of every family was required to serve.

The war changed him dramatically, Ingurazova says. He killed a man for the first time, buried his first friend, took his first drugs. His wife eventually left with their child to start a new life elsewhere. In the last days of the war, he survived a mine blast that killed three friends from his hometown and left him scarred and almost deaf. Then he retreated to the mountains to live a life of self-imposed exile, which was more bearable to him than witnessing the fallout that ensued once the war ended.

Wolf’s story was one of the several Ingurazova was focusing on for her project, and eventually it became clear to her that he was the story. She came to understand that the pain he endured was symbolic of the trauma experienced by the entire region. He’s since become the main character, the lens through which Ingurazova shows us the story of this place and its people.

Sharing his story has helped him face his past, she says, to feel the tragedy less and to begin to heal.

The most powerful takeaway for Ingurazova was finding that in the midst of all of that, life goes on. This sentiment also parallels her own as a photographer. “Photography is about staying,” she says, and coming away with a deeper understanding. Even if it’s uncomfortable.

See more of Ingurazova’s work on her website.