Endangered color

A tiny blue frog, a shy red panda, and a vivacious green parrot are all connected by one worrying quality: they are all on the edge of extinction.

Think of nature and we think of color: a red sunset, a green forest, a blue ocean. Such scenes, simply described and instantly imaginable, are actually made up of a myriad of hues, tints, and tones—combinations of color that make nature so spectacular. For wildlife, color has a purpose: often to blend in or to stand out. Both can be crucial to a creature’s survival. An animal’s distinct coloration, the product of thousands of years of evolution, give it the optimum appearance for attracting mates or hiding from predators. But it is not enough to save some animals from the threat of extinction: the red panda, thick-billed parrot, and blue poison dart frog are three icons of the world’s endangered color.

High in the crisp, cold air of Asia’s mountain forests, a red panda blends into the rusty brown branches of a tree. Keeping a low profile, its thick russet fur blends in well among the red-brown moss that clings to the tree as closely as the animal itself. For the red panda, its colors are crucial camouflage: not only are these animals shy and solitary by nature, they are also hunted by predators―from domestic dogs to snow leopards. For a life lived in the trees, the red panda’s ruddy colors are perfect.

But while the red panda is rightly described as red, it is not a panda. The taxonomy of the red panda has baffled scientists since it was first described in 1825. Originally classified as a racoon and then as a bear, it is actually its own family—Ailuridae. However, it does share some traits with its much larger black-and-white namesake: an enigmatic bear-like face, a wrist bone evolved into a thumb, and a taste for bamboo. Something else it shares is that it is a threatened species.

The red panda population has declined sharply, and perhaps as few as 10,000 individuals remain in the wild. Their natural habitat, the high-altitude forests that range from Myanmar to southwest China, have been eroded by logging and farming. It has reached the point where inbreeding among isolated communities is a problem. International efforts to protect the red panda’s remaining habitats have had some success, bringing hope that this species will continue to hide among the moss-covered trees they call home.

Far away in the mountains of Mexico there is a flash of brilliant apple-green against a dark snow-laden sky; with a sudden shriek, a thick-billed parrot dives into the pine forest below. It is a maneuver that has kept thick-billed parrots alive for millennia. Hunted by hawks and falcons, these intelligent and sociable birds usually flock together for safety. When caught alone, they issue a sharp cry of warning, and use their powerful flying skills to dive into the trees where few predators will follow.

However, it is in the forest that the thick-billed parrot’s vivid green feathers reveal their true colors. While we may think they draw attention, among the bright-green pine needles the birds’ feathers act as camouflage. Green is a common color in nature, but parrots make green in an unusual way. The physical structure of their feathers reflects light to appear blue, but the birds’ also have an underlying yellow pigment. It’s this combination of blue and yellow that creates the bird’s brilliant green plumage.

Nature intended this color to protect the parrot, but it also brings problems. The thick-billed parrot is prized for its brilliant plumage and has been hunted for the illegal pet trade. Habitat loss is also devastating thick-billed parrot populations. There are only around 1,000 breeding pairs left in the wild—half in a single 6,000-acre area of forest. Following failed attempts to repopulate habitats and release captive-bred birds, efforts are being made to help more chicks survive and grow the species. We are still a long way from seeing flocks of thick-billed parrots turning the skies green over Mexico.

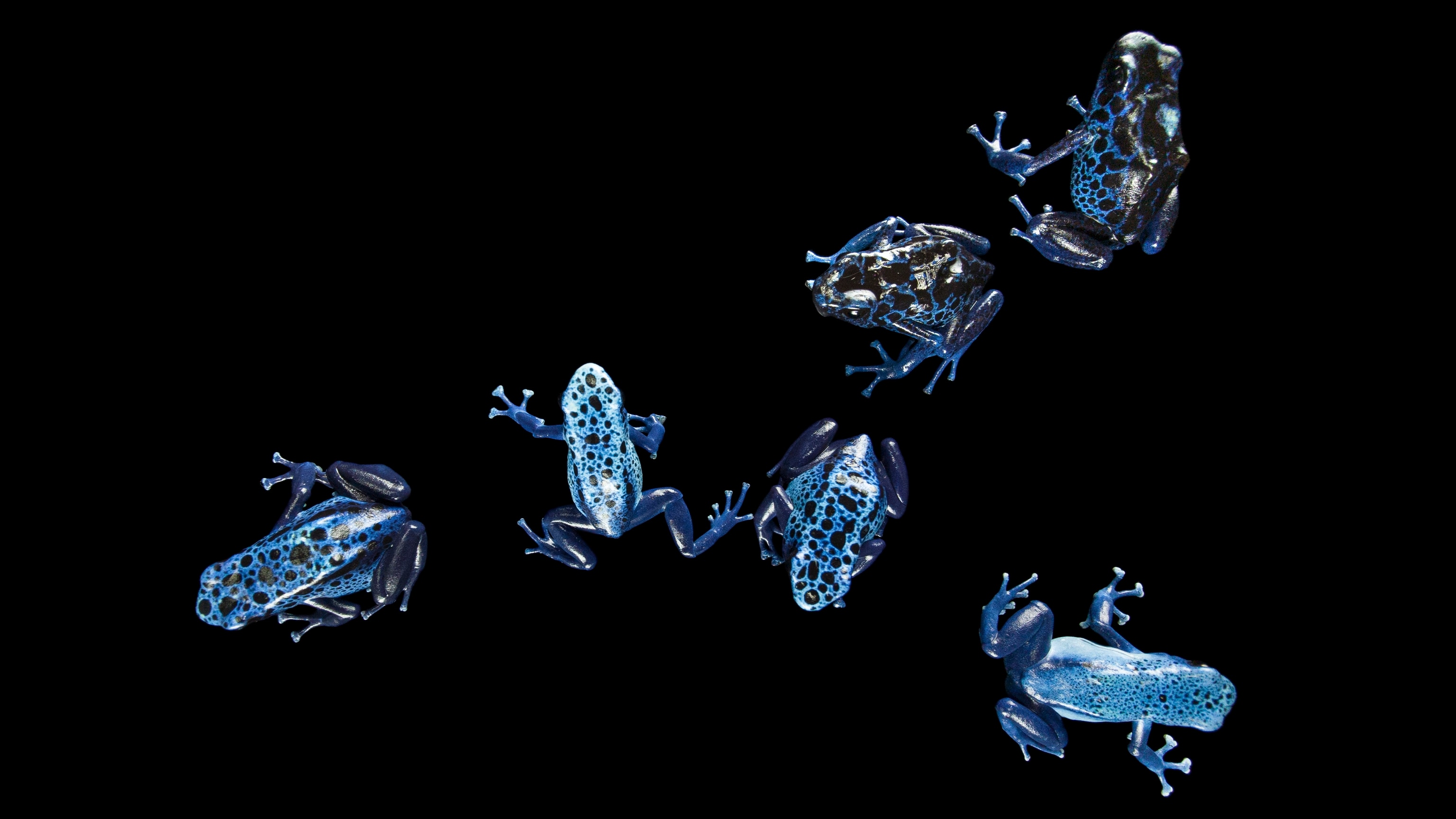

In the rainforests of Suriname, a snake stalks a small bright-blue frog. The frog makes no attempt to hide and the predator makes no attempt to attack. The key to this bizarre standoff is color—this is a blue poison dart frog. Its bright blue skin makes it stand out among the green and brown of the forest floor because this tiny frog actually wants to be seen. Through generations of experience, predators know that out of all the frogs on nature’s menu, bright blue frogs taste bad. The color is a warning.

Surprisingly, blue is a rare color in nature because it is very difficult to make. The blue poison dart frog is neither blue because of natural pigments nor because of the food it eats—though that does account for its highly toxic skin. Instead, the frog appears blue because it has irregularly shaped microscopic cells called chromatophores which reflect blue light. These also create its distinct tints and shades: azure-blue legs; darker blue belly; and sky-blue back with a pattern of black spots as unique as human fingerprints.

While being bright blue protects the frog from predators, it does not protect against everything. Dangerously restricted to a few isolated areas, the blue poison dart frog is susceptible to chytrid, a virulent fungal disease that is devastating amphibians around the world. It could be that captive breeding programs are the best way to ensure the survival of the species so that its beautiful blue does not disappear forever.

There is a real danger that these animals and their unique colors could be lost from nature. This has inspired global mobile phone manufacturer, OPPO, to support the National Geographic Society’s wildlife conservation efforts around the globe. With funds distributed among a range of wildlife projects, OPPO is supporting crucial research, exploration, and conservation. This is better equipping National Geographic to raise awareness about the growing threat of species loss and to help protect endangered species on the ground.

One such program is Joel Sartore’s Photo Ark, a 25-year project to photograph every one of the 15,000 species in human care. The photographs Joel makes use black or white studio backgrounds to help focus attention on the coloration of his animal subjects. It’s a technique that OPPO appreciates with their passion for capturing true color. The OPPO Find X3 Pro is the first Android phone to deliver an astonishing one billion colors end-to-end—from capture through processing to display. No other smartphone can portray nature’s vast pallet as completely and authentically, from epic landscapes with a best-in-class, ultra-wide-angle lens to a 60x magnification that brings your subject even closer. The OPPO Find X3 Pro enables anyone to capture and share the true reds, greens, and blues of our natural world, inspiring even more people to admire, appreciate, and preserve the endangered colors of our planet.

Join OPPO in support of National Geographic Society and its wildlife conservation efforts