London, July 26, 1609: Our first giant leap towards the Moon

From a home observatory in a London house on July 26, 1609, an epic journey began both for exploration, and for the lives of two pioneers: one famous, one not so much.

The headlines would belong to Galileo Galilei when he pointed a long wooden tube inset with glass lenses at the moon in November 1609, and began to draw his place into history. But unbeknownst to the illustrious 17th century Italian physicist— unbeknownst to just about everyone, in fact—four months earlier from the eaves of a home observatory in Kew, West London, the great Galileo had been astronomically gazumped.

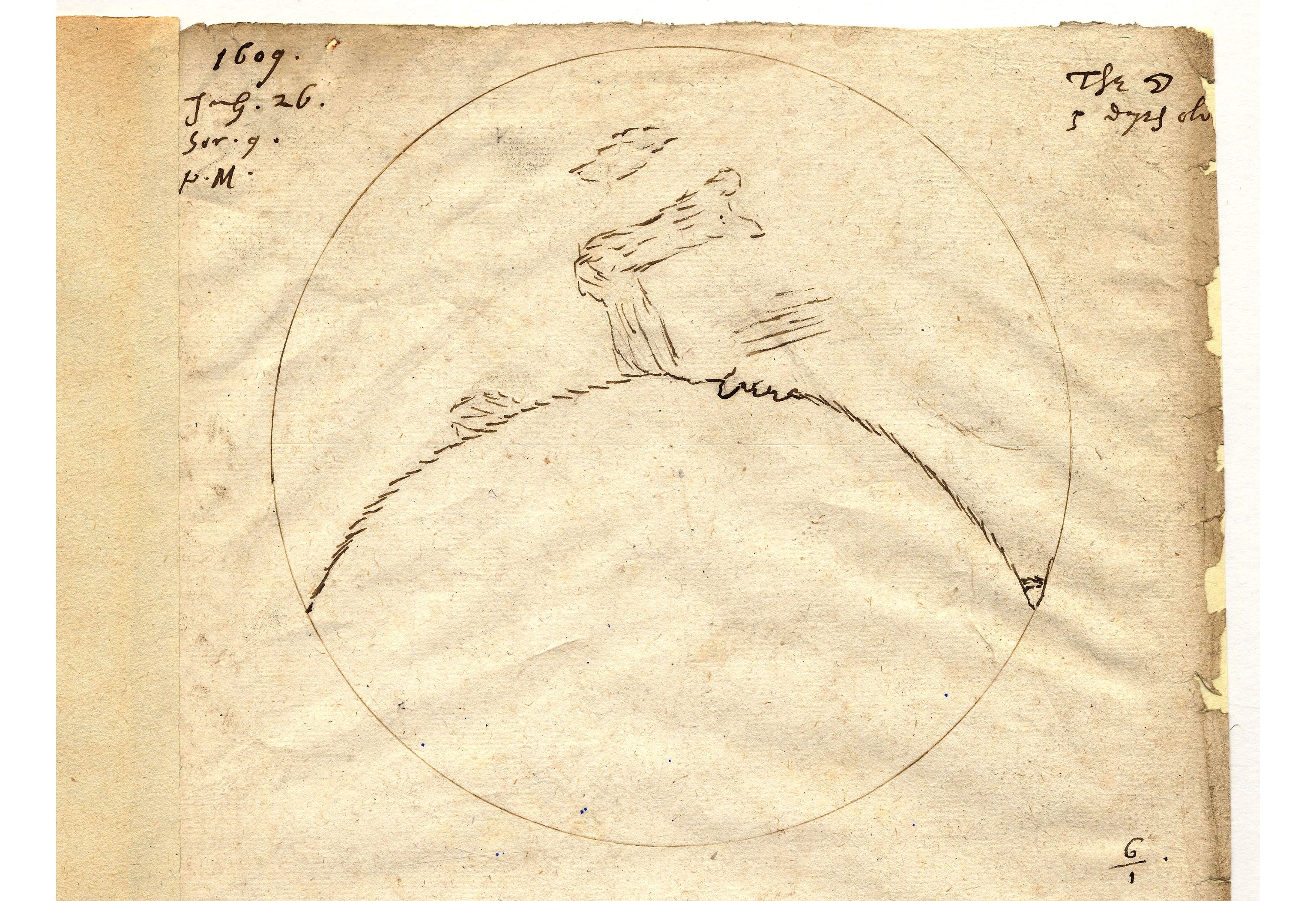

The proof: a series of dog-eared sketches, the first dated in a florid hand to the 26th July 1609—and depicting what at first glance appears to be an elaborate coffee stain. This is, in fact, the first known drawing of the moon through a telescope. The man holding the quill: a British mathematician by the name of Thomas Harriot.

“Today, when we are so used to seeing detailed images of the Moon, the July 1609 sketch can be quite difficult to appreciate,” says Megan Barford, Curator of Cartography at the Royal Museums Greenwich. "The shading indicates what we now describe as mare (lunar ‘seas’, which are actually plains of solidified lava), probably the Mare Crisium, Mare Tranquillitatis and Mare Foecunditatis. The curved line is the terminator, the edge of the illuminated surface of the Moon.”

Observations from afar

The margins between Harriot and Galileo were relatively slender in Harriot's favor at the outset, but would later overlap in both in time and type: Harriot's first sketch was made in July 1609, whereas Galileo's were made in late November and early December of the same year from his house in Padua, near Venice.

Before 1613 both men would observe the moons of Jupiter and sunspots, each apparently independently. But Harriot and Galileo's 1609 observations were made possible by a new instrument created by a Dutch-German spectacle maker named Hans Lippershey, who just the previous year had built what he called the 'Dutch trunke'—to all intent and purposes, the first telescope. The idea quickly caught on.

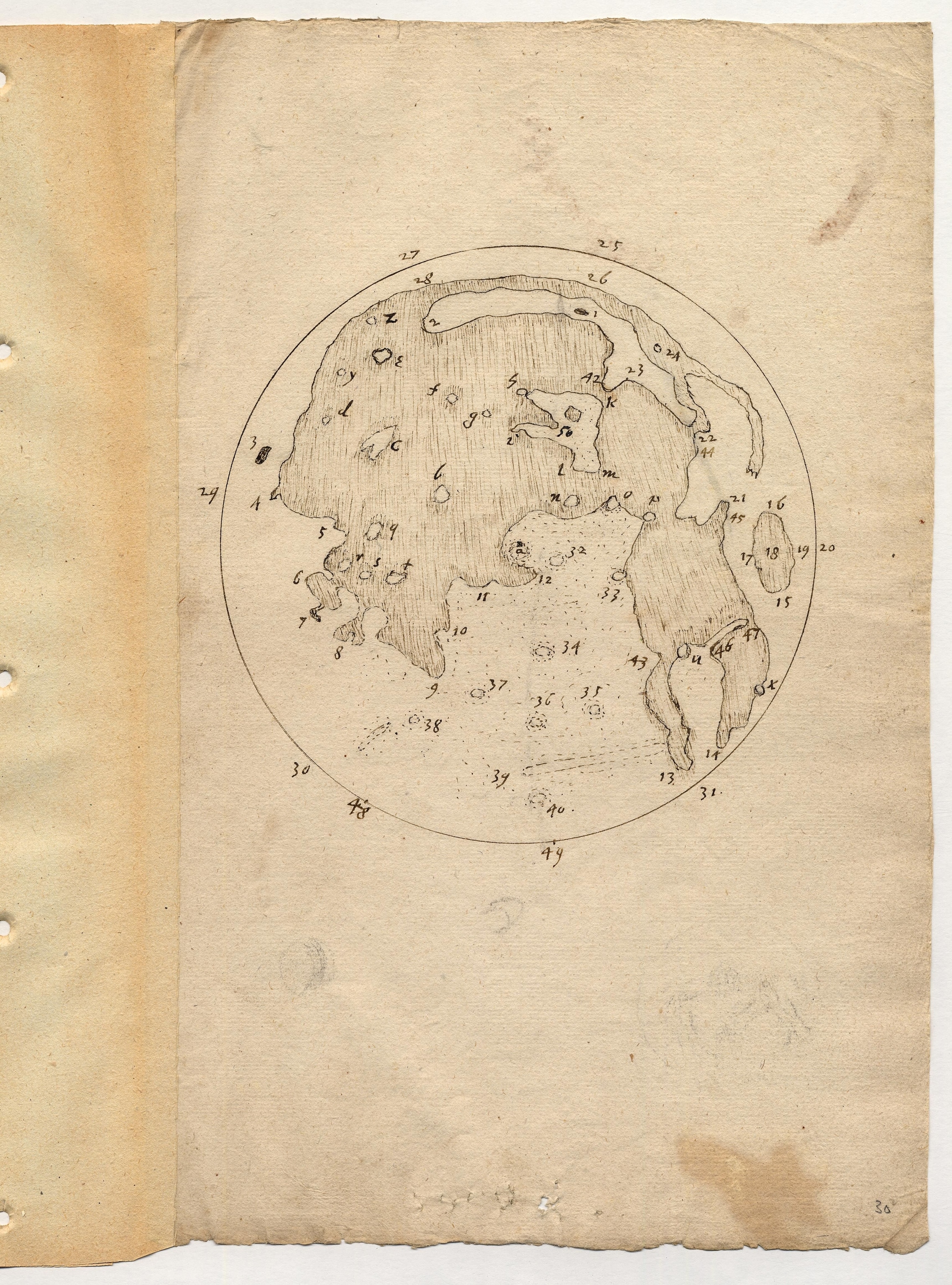

“The telescope which Harriot used to make the earliest extant drawing had a x6 magnification, which was less powerful than most binoculars readily available today." continues Megan Barford. “The next sketch of the Moon by Harriot which survives is from around a year later, and this and his later images, made with more powerful telescopes, are more detailed and refined.”

Remarkably, this second sketch—assembled, it's thought, from as a composite from previous observations—attempted to make order of the dark patches on the moon, creating a kind of map of the lunar surface in the process.

While Galileo would become famous (and infamous) for his work, the reason Harriot's drawings didn't surface widely at the time are likely down to the circumstances of his employment: in short, he didn't need the acclaim, or the money. “Harriot had a wealthy patron in Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland.” Says Megan Barford. “His life was certainly comfortable, and secure—he had a salary of £80 in 1598, and £100 from 1616. He worked in a world of mathematical and astronomical communication which was based on correspondence and conversation, rather than printing and publishing.”

Parallel lives, colorful persecutions

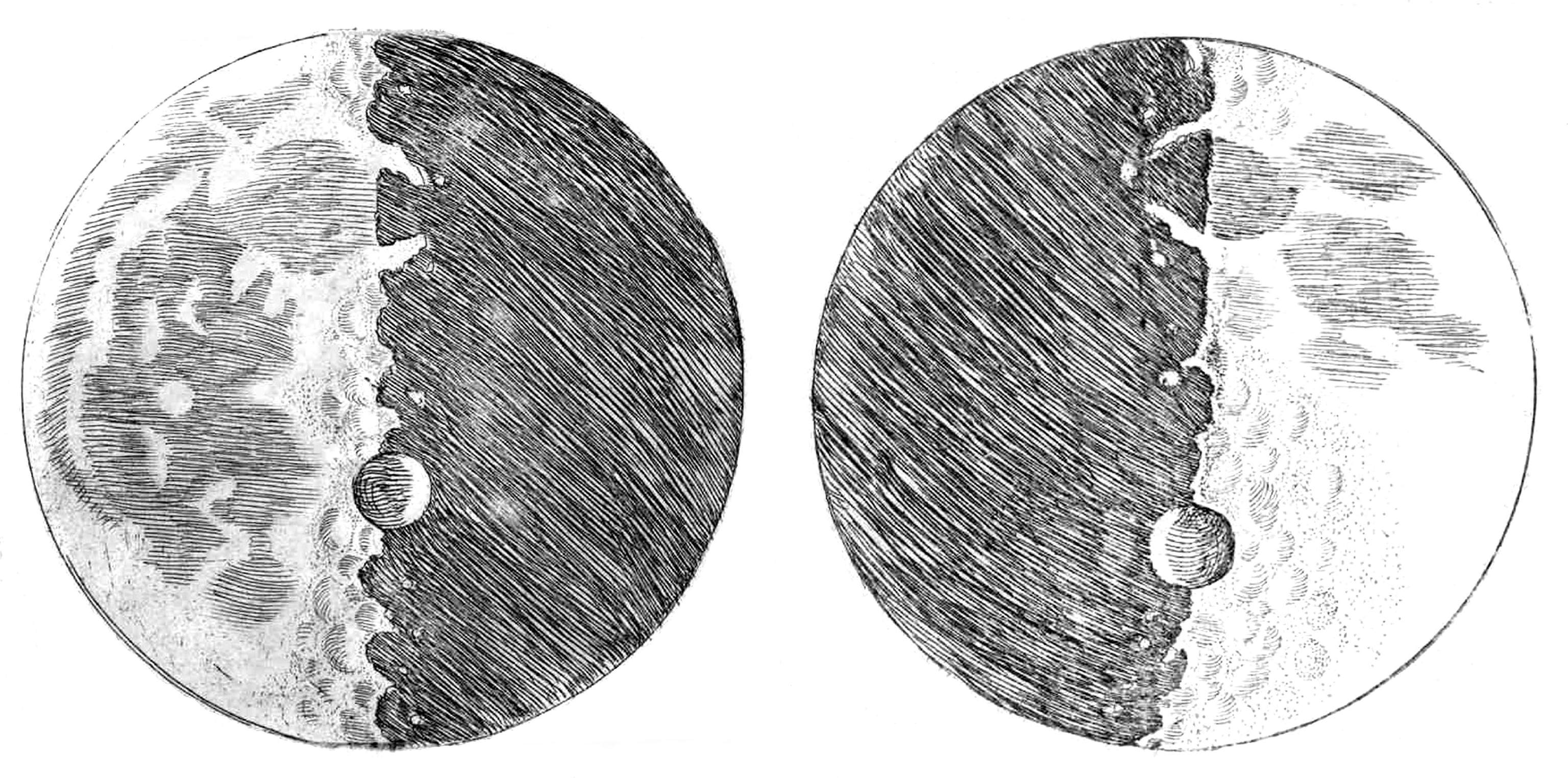

Credit must be given to the polymathic Galileo, for not only designing his own telescope (Harriot had bought his from the Netherlands) but for the myriad of elegant deductions he made from his own observations of the moon and other celestial bodies. He was the first to note the moon as an inferior sphere, and as being a place of heavy relief like the earth—which he deduced by noting the presence of craters and the behavior of shadows. “I have noticed that the small spots... have the dark part towards the sun’s position, and on the side away from the sun they have brighter boundaries, as if they were crowned with shining summits,” he wrote in 1610.

Like Harriot, he also made observations of sunspots—in this he is thought to have also just been pipped to it by his English contemporary—and realised that the ‘stars’ he observed around Jupiter were actually moons. This led to his theory that these smaller celestial bodies orbited the planet, and therefore that the planets likely orbited the sun, rather than the other way around.

“Compared to similarly outspoken Bruno, Galileo got off lightly: he remained under house arrest. Giordano reputedly had a spike driven through his tongue before being hung upside down, stripped naked and burned at the stake.”

While all have been proven since as loud shouts of eureka in our understanding of the universe, Galileo would suffer for his insight: like Copernicus centuries earlier, his observations vindicated the idea that the Earth wasn't, as per Catholic doctrine, the centre of the universe after all. Galileo's 1610 book Sidereus Nuncius—the 'starry messenger'—contained detail of his many early observations and caused outcry in the church; he was tried and convicted of heresy in 1633. Compared to similarly outspoken Giordano Bruno, who was convicted for making similar statements about the principles of the universe in 1600, Galileo got off lightly: he remained under house arrest until his death in 1642. Giordano reputedly had a spike driven through his tongue before being hung upside down, stripped naked and burned at the stake.

Harriot, meanwhile, appears to have led a life that was no less peculiarly eventful— though most of Harriot's (mis)adventures occurred before he turned his eyes to the stars, rather than as a result. Harriot had sailed to Roanoke, Virginia in 1585 at the bidding of Sir Walter Raleigh, where he had been one of the first to translate the Algonquian language from natives there—and one of the last to see the colony before its mysterious disappearance.

Suspected of being involved in the gunpowder plot due to a family connection, the 9th Earl Henry Percy was arrested on charges of treason in 1605, and Harriot along with him. (Harriot was released; Percy would spend over 15 years in the Tower of London). He later witnessed the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1618, before succumbing himself to probable skin cancer in 1621.

A colourful life—and an obscure but significant place in the very first steps of lunar exploration.