He returned to the ‘cave of bones’ to solve the mysteries of human origins

To unearth the secrets of an ancient human relative, paleoanthropologist Lee Berger had to squeeze through a chute seven and a half inches wide—the length of a pencil.

“I think we should stop the excavation,” I said.

As I gestured at the ghostly image on the computer screen, I looked over at Keneiloe Molopyane, an archaeologist and forensic scientist known on our team as Bones. We were watching a live stream of two colleagues, archaeologists Marina Elliott and Becca Peixotto, digging around a hundred feet beneath us. Bones leaned in to look at the screen as the light from the excavators’ head lamps darted around the chamber. “Why stop?” she asked.

It was November 2018, and we were sitting at our team’s “command center” in South Africa’s Rising Star cave system, which comprises nearly two and a half miles of interlaced passages, descending in some places more than 130 feet underground. Occasionally, you might find a chamber in which you can sit up or even stand. But most of the open spaces are relatively small. Marina and Becca, our two most experienced excavators, were at work in one such space, Dinaledi.

Sediments in these caves formed through dust and debris slowly coming off the walls and blanketing the floor in nearly invisible layers. But the sediment that Marina and Becca were scooping out didn’t have that same level of uniformity. It appeared as if it had been disturbed. “It looks like there was a hole in the floor of the cave,” I told Bones. “I don’t think it’s a natural depression. It looks a lot like a burial feature to me,” I concluded.

(Related: Humans in California 130,000 Years Ago? Get the Facts)

Bones’s eyes widened: “It does.” She considered the on-screen image again. “I think you’re making the right decision,” she said. “We should stop.”

I didn’t know it then, but that decision would lead to a scientific revelation—and some of the most terrifying, and most wondrous, moments of my life.

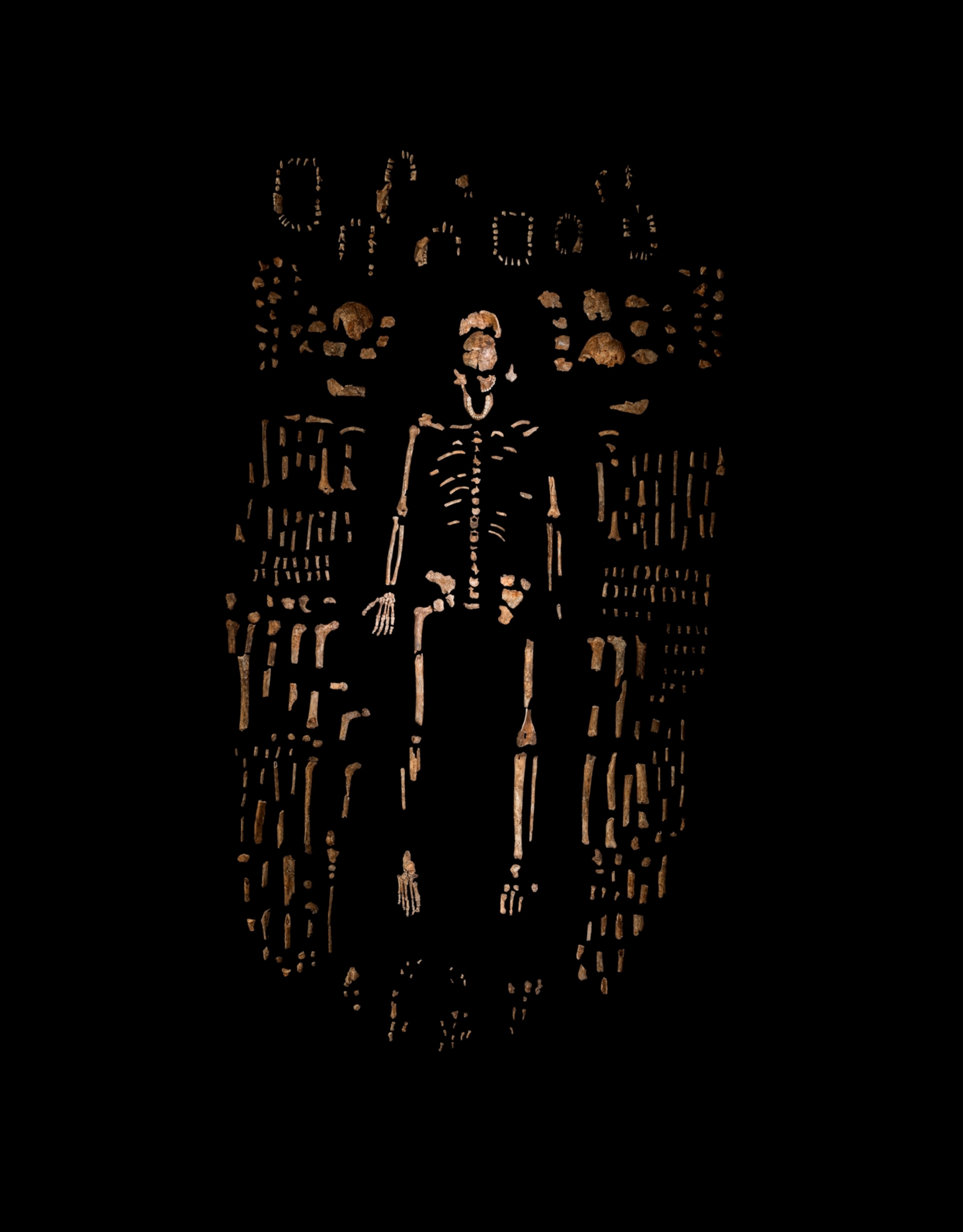

Our previous work at Dinaledi, in 2013 and 2014, was astonishing. In less than two months’ time, my team had recovered more than 1,200 fossils—primarily bones and teeth—from a spot within Rising Star no bigger than 10 square feet.

(Related: Ancient Roman Giant Found—Oldest Complete Skeleton With Gigantism)

As we described in more than a dozen scientific papers, those fossils were unlike anything paleoanthropologists had ever seen. The remains represented a new species of primitive human relative we named Homo naledi: Homo, because it belonged in the genus shared by other humans, and naledi, meaning “star” in Sesotho, a common language in the cave system’s region of South Africa, about 30 miles northwest of Johannesburg. We named the chamber Dinaledi, or “chamber of stars.”

The biggest find from our excavations in 2013 and 2014 was a skull of H. naledi that sat within a complicated array of bones and bone fragments: leg bones, arm bones, pieces of hands and feet. We named this tangle the Puzzle Box. Excavating it felt like a high-stakes version of pick-up sticks, in which each piece had to be carefully extracted without disrupting the others. In total the Puzzle Box grew to an area of about a yard across and was packed with fossil remains.

(Related: When Is It Okay To Dig Up The Dead?)

We had returned to the Puzzle Box in November 2018 to test whether Dinaledi had a continuous layer of bones. We dug two new excavation squares: one south of the Puzzle Box and one north of it. The northern square revealed a concentration of fragments that looked as if they’d come from one individual. Further digging revealed a sterile area of no bones, and then another concentration of bones containing a jaw and limb bones in disarray, preserved at all angles.

As Marina and Becca removed sediment one spoonful at a time from the area that Bones and I were puzzling over on the live stream, they uncovered a concentration of bones about as large as a medium-size suitcase. Oddly, the surrounding sediment contained only a few fragments—or no bones at all. It didn’t make sense. If the bones had flowed into the chamber, why had the fossils clustered? Why was there empty space between them?

For years we had worked in Rising Star knowing that H. naledi had occupied these spaces, and we had reason to suspect that they used Dinaledi as a repository for their remains. But “deliberate body disposal”—the language we had all carefully used in our earlier work—is very different from “burial.” In our 2015 papers describing H. naledi, we suggested that the bodies found in Dinaledi could have been either carried into the cave or dropped down, perhaps through the chimney-like passage we called the Chute. Burial, on the other hand, is something more intentional: a body being purposely interred and then covered.

Archaeologists have found surprisingly little evidence of burial among the earliest members of our species. The oldest clear cases were found in Israel, believed to be between 120,000 and 90,000 years old. Neanderthals also sometimes buried their dead, although the best evidence of this behavior comes from fairly late in their existence, less than 100,000 years ago. Our tightest constraints on the age of H. naledi date further back, to between 335,000 and 241,000 years ago.

H. naledi was Homo, but with a brain one-third the size of ours, it was far from human. Scientists might accept that large-brained hominins like Neanderthals could exhibit complex behavior, but the idea that H. naledi engaged in anything of the sort was a harder pill to swallow. It was a radical idea, then, to propose that Rising Star might contain a burial site. Burial was too human an activity: It took planning, a shared intention across a social group, knowledge of the permanence of death.

By early 2022 the possibility that we were uncovering H. naledi burials had grown stronger. We had H. naledi fossils from many different areas in Rising Star, including the Puzzle Box, Dinaledi itself, and another chamber more than 328 feet away. Scans of one rocky block that we had carried out of the cave system revealed a child’s body, almost certainly of H. naledi, curled up in a space smaller than a laundry basket, with the remains of two or three others thrown into the same hole or right next to it. A crescent-shaped object denser than the bones—a possible stone tool—was sitting right next to the most complete skeleton’s hand.

Now we had significant questions to answer and a radical, controversial argument to make: A nonhuman species with a brain barely larger than a chimpanzee’s was burying its dead.

The team and I had to make every effort to ensure we gave the world all available data in a clean, comprehensible way. In all the breakthroughs at Rising Star, fewer than 50 of my co-workers had shimmied down Dinaledi’s Chute, a 39-foot-long vertical passage. Its narrowest part was just seven and a half inches across. I myself had told thousands of people about the perils of this space over the years.

Despite leading this research for nearly a decade, though, I could only ever picture the nature of the space in my imagination. I filled in details by watching others on the computer screen via cables we had strung through the cave system, by reviewing maps, and by marveling at the fossils.

Now Dinaledi had yielded its biggest surprise yet, and seeing it at a distance would not be enough. If that meant I had to risk life and limb to get down and interpret it up close, so be it.

Before I could think about navigating the Chute, however, I had to worry about fitting into it in the first place. To be blunt, I needed to lose weight. I was approaching my 57th birthday. I wouldn’t have many years left to try. I made my own diet and exercise plan, and while my family gave me lots of encouragement, I didn’t tell them, or anyone else, about my plans. Over the next few months I lost 55 pounds, and I was feeling as fit as I had been for decades.

On the day of my attempt, which took place in July, I woke up at five in the morning and pulled on my blue jumpsuit. I spent half an hour checking batteries for my helmet light and other gear I would be taking in my backpack. Then I sat down on the bed to lace up my calf-high British military boots and stared at the walls of the bed-and-breakfast, trying to think positive thoughts. My mind went to my wife, Jackie, who was probably just waking up to head to work. I thought about our two children, Megan and Matthew. Both had been down the Chute; both knew how difficult and dangerous it could be.

I still hadn’t told any of them what I was about to do. I had enough doubts about my ability to get through the Chute. A small part of me knew that it probably wouldn’t take much for a close family member to talk me out of it.

There’s always a moment of doubt before doing something dangerous, and I had plenty of doubt as my feet slid into the Chute’s narrow abyss. Face up against solid rock, my jumpsuit snagged on crags in the stone, and my thighs barely fit inside the fissure. My helmet light cast eerie shadows around me. With my lower body already inside, I took a deep breath and envisioned the narrow confines I was entering. I pushed against the ancient gray rock. Damn, this is tight, I thought. I dangled half in and half out of the opening. This was just the beginning.

I looked up at Maropeng Ramalepa, a member of my exploration team and the “Chute Troll”: my guide for this first half of the descent. He crouched at the opening and offered a broad smile. “You got this, Prof!” he said. I answered with a grunt, my breath already steamy in the cool cave air. A few minutes later I took a deep breath, rolled onto my back, and inched my way downward.

As I twisted my boots to fit into the top of the Chute, the odd angle of entry forced me to shove my face into the rock. Gravity assisted me until my chest caught. I twisted and pushed until the dark tunnel wall overtook my vision. I hadn’t expected the walls to be so damp; I struggled to find purchase on the slick surface. At Maropeng’s instruction, I lowered myself into an alarmingly small slot in the rock behind me and to my right. My boots barely fit within the gap.

I could hear Dirk van Rooyen, the lead for today’s descent, moving below me in the darkness. “How’s it going?” he shouted. “So far, so good!” I yelled. I was about to make a major commitment: If I continued to lower myself, I would have no choice but to shove the widest part of my body through the slot. I grimaced. This route would be my exit too.

I closed my eyes, then wriggled into the gap, my right toe stretching for the tip of a large stalagmite near Dirk. With great difficulty, I managed to corkscrew on my toehold like a ballerina. I took a shallow breath and pushed my way into the space.

This was nuts.

Now that my body had reached the pinnacle of the stalagmite, I was literally hugging it—my cheek pressed against the wet rock. As I caught my breath, resting, I looked about. This space wasn’t a chute at all, I realized. It was even different from the drawings in our scientific papers and articles. Ever since its 2013 discovery, we had described it as a chimney: a single, vertical passage. In reality it was an intricate network. I imagined H. naledi scrambling through these spaces, adults and children climbing through whichever passage they preferred, unlike us relatively bulky humans. It was a labyrinth of opportunity.

I continued downward, and the passage forced these revelations to the back of my mind. My hips passed through the seven-and-a-half-inch squeeze, but as I slid my chest into the gap, a cruel knob of rock jabbed into my sternum. I felt the bone bend. “This rock knob won’t let me pass!” I cried.

I contemplated my options. Looking up, I saw Maropeng sitting above me, near the entrance to the passage. To one side was a climbing rope, stretching from me to Maropeng, used to guide equipment through the caves. I wound the rope around my right wrist as much as I could. “Maropeng!” I called. “When I tell you, can you give me a pull? I am trying to free myself!”

I felt the rope tighten around my wrist. “Pull!” I shouted. The rope went taut, and I pushed hard with whatever leverage I could find. It was just enough to lift me an inch or two, freeing my chest. My shoulder twinged with pain.

I looked at the impassable rock, my mind racing. I had assumed for nine years that the Chute was a special pathway and important for understanding H. naledi’s behavior. But I had been wrong. There was nothing special about it, except that it could fit humans. We had been making this journey unnecessarily hard on ourselves.

I made a decision. “Dirk, can you take this knob off?” I asked. If Dirk had any reservations about damaging the passage, he didn’t show them. With nothing more than a few swift strokes, he broke off the pestering chunk with a rock hammer. This time, it no longer caught my sternum. I clenched my jaw with pain. But then I was free. I continued picking my way downward, my body seemingly contorting like toothpaste in a gnarled tube.

After more than a few minutes, the tip of my boot brushed the top of a ladder. I could hardly believe it. This was the ladder that our team had specifically designed for Dinaledi. Whenever someone made it this far, our team issued a call from the command center, a signal that their grueling passage was over: Marina has reached the ladder. Becca has reached the ladder. Kene has reached the ladder.

“Berger has reached the ladder.”

I stepped onto the floor of Dinaledi and closed my eyes. Tears welled. For more than eight years—ever since its discovery—I believed that I would never set foot in this space. The journey had been horrible, but I had already learned so much. The pain and fear were already worth it. Now I needed to make the most of the hours ahead.

I pulled out my phone and dialed my wife’s number for a video call, via the cave’s internet system. When she answered, I smiled at her: my face filthy and sweaty, my voice full of elation.

“Guess where I am,” I said.

“In a cave?” she quipped.

“I’m in the Dinaledi chamber,” I said. “I got in!”

Surprise shot across her face. “And getting out?” she asked.

“If I can get in, I can get out,” I replied.

Truthfully, I wondered whether I would be able to keep my promise—the exit was at least as difficult as the journey here, if not more so.

But that fear would have to wait. Now I needed to explore.

This story appears in the July 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.